Across the multimanagerverse

Our mainFT colleagues Harriet Agnew and Ortenca Aliaj have written a great piece on the recent dominance of the multi-manager hedge fund model, and the mounting challenges it now faces.

It’s a subject Alphaville is interested in, so we thought we’d dig in a bit as well, using some of the investment bank research that they cited. Read the FT Big Read first though, it’s worth it just to see Ken Griffin (!) calling the multi-manager top.

We suspect this could be because he wants to dissuade anyone from trying to replicate what he has built at Citadel. But this chart from Barclays shows that the halo around multi-manager shops has faded a bit this year, after years of industry outperformance (zoomable version):

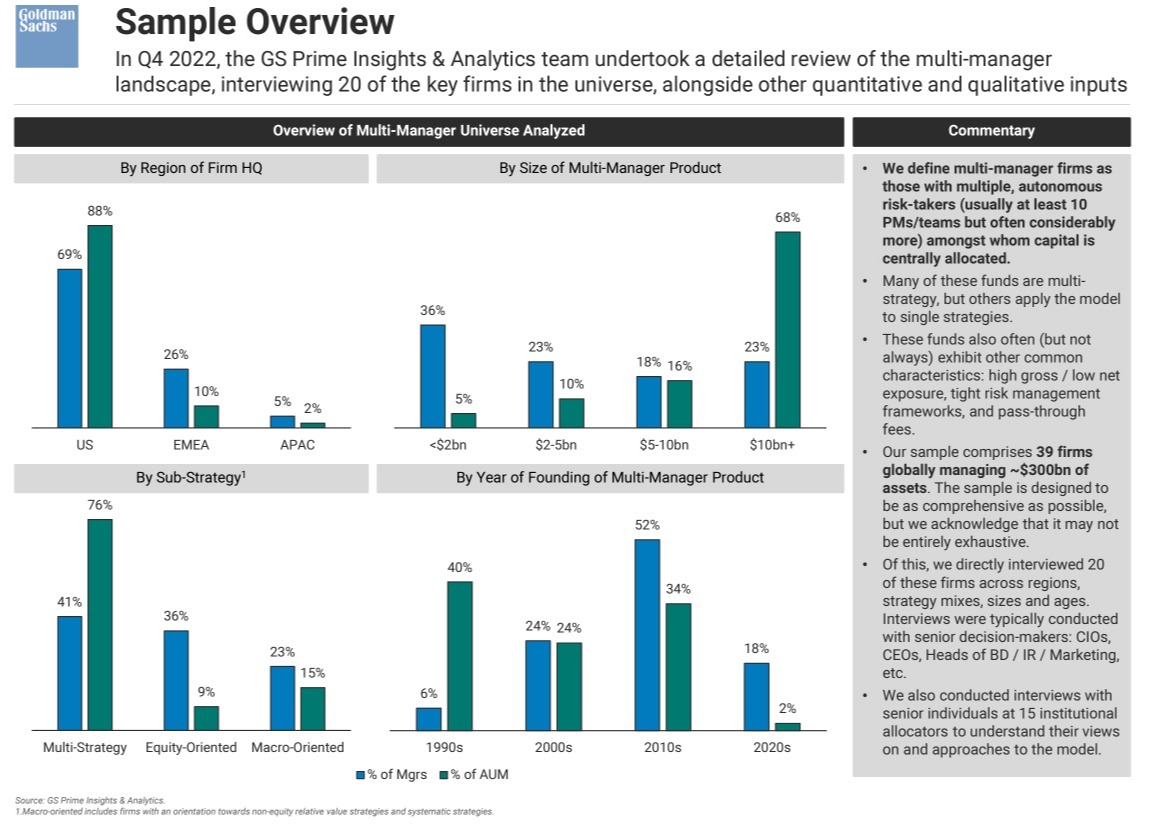

First of all, though, it might be helpful to clarify what multi-managers are, and how they relate to “multi-strategy” hedge funds. The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, even by us, but there are some important distinctions.

Multi-strategy is the broad term for hedge funds that combine a lot of different investment styles and strategies, with risk managed centrally and capital and leverage allocated to teams of traders, or “pods”, according to how well they do. (Or what the chief investment officer thinks will offer the best future returns.) This all happens under the hood; investors typically invest in one fund with fixed fees that combines all the individual profits and losses.

A good example of a multi-strategy firm is DE Shaw, which is mostly known as a quant hedge fund, but whose flagship Composite Fund actually combines a lot of systematic, discretionary and hybrid strategies.

Multi-manager hedge funds are a subset of this category, albeit the most prominent type because of the success of Citadel and Millennium. Multi-managers don’t have to be multi-strategy — some employ multiple autonomous pods within a single style, such as equities or macro — but most are. Citadel and Millennium employ hundreds of teams that do almost anything you can imagine that involves tradable securities (and a few you probably can’t).

Here is how the MM subset breaks down by region, style, age etc, courtesy of Goldman Sachs (zoomable version):

These shops are known for being particularly ruthless with underperforming fund managers, but otherwise tend to let each pod operate almost as an independent hedge fund.

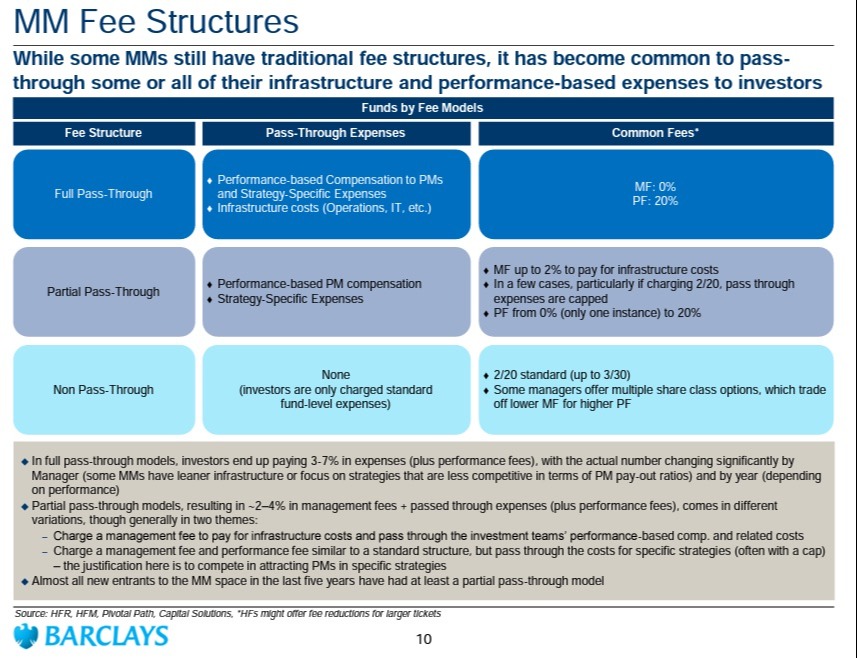

Another defining feature of most (but not all) multi-manager outfits is so-called pass-through fees. While most hedge funds charge a fixed management fee (say, 1 to 3 per cent, typically) and take a slice of their profits (10 to 20 per cent), pass-through funds instead pass on almost all their expenses to investors. In practice this ends up being way more expensive, with 5 per cent plus annual costs common.

Here’s what that looks like (zoomable version):

So, put this with some concrete examples:

DE Shaw rarely (if ever?) sacks entire trading teams, and charges a fixed 2.5 per cent management fee and takes 35 per cent of profits thrown off by its Composite fund. Citadel chomps through portfolio managers like they’re popcorn, charges investors for almost all its expenses (from salaries and Bloomberg terminals to canteen food and flights) and takes 20 per cent of the profits it makes.

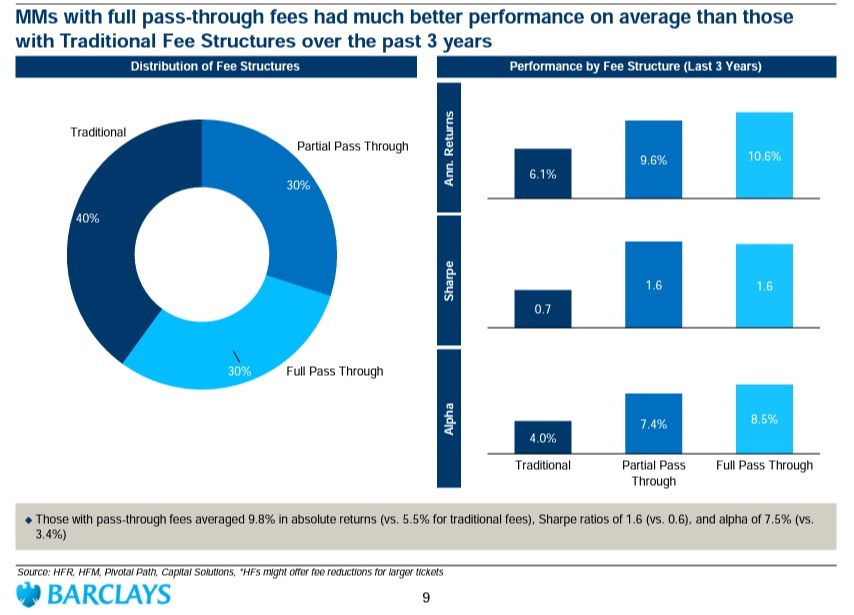

Citadel’s strategy may sound mad; it does even to a lot of other hedge fund managers. But investors are OK with it, because multi-managers with full pass-through fees have generally fared better than those with traditional fee structures, as this Barclays chart shows (zoomable version):

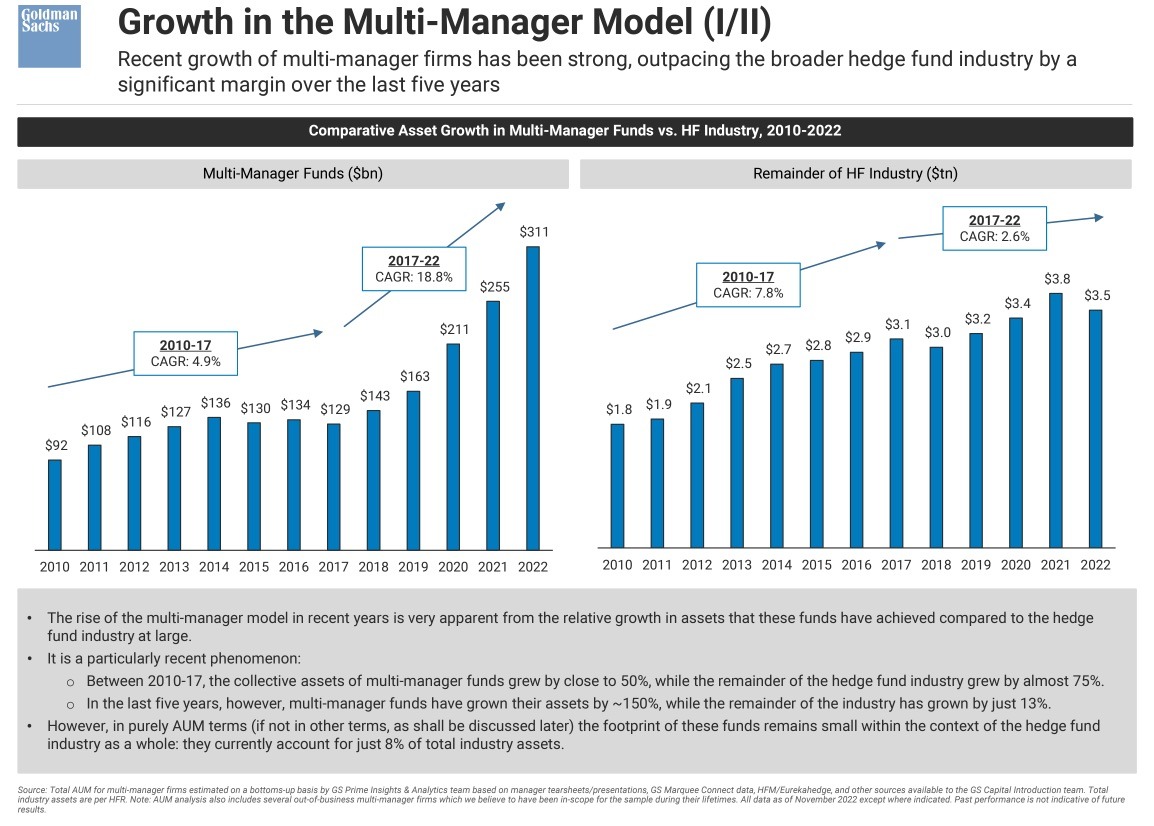

As Griffin pointed out, hedge fund styles wax and wane in profitability and popularity (for example, macro was dead until it suddenly wasn’t, likewise with CTAs) but the past half-decade has definitely been the era of multi-manager shops.

According to Goldman Sachs, they now manage $311bn despite several of the biggest multi-manager firms having been closed to new capital for close to a decade.

That means they make up about half the broader $600bn multi-strategy hedge fund universe, Meanwhile, the rest of the hedge fund industry has stagnated (zoomable version).

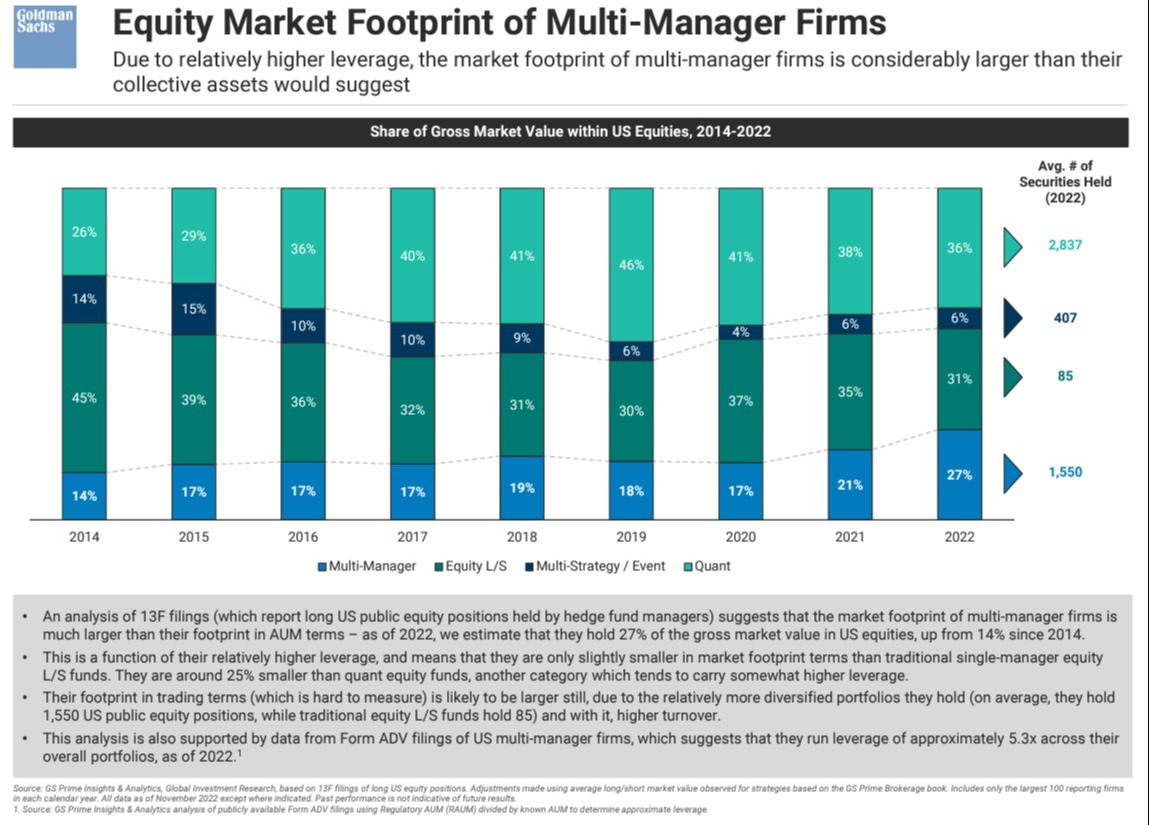

However, multi-managers often use massive amounts of leverage on many of their strategies, confident in their ability to manage the risks centrally. As the mainFT’s Big Read pointed out, that means that their market footprint is outsized.

Based on regulatory filings, Goldman Sachs estimates that multi-managers use about 5.3 times leverage on average. Not quite LTCM levels, but sizable, and in some strategies (eg Treasury basis trades) it will be much higher.

Here’s a Goldman chart showing how multi-managers account for 27 per cent of the entire hedge fund industry’s overall holdings in US equities, up from 14 per cent since 2014 (zoomable version):

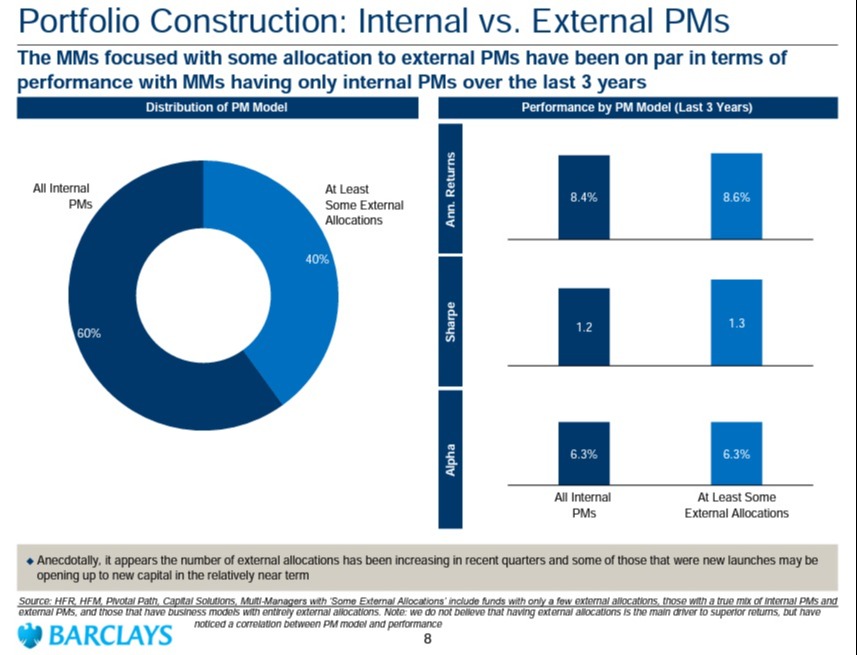

One fascinating thing we learned from the FT Big Read was how common it has become for multi-manager hedge funds to allocate money outside their own firm.

That’s presumably because 1) the competition for talent is fierce and expensive, 2) their own investment capacity is limited, and 3) they have such a cachet with investors at the moment that it is tempting to take their money, charge fees on it and “rent” capacity elsewhere.

This slide from Barclays indicates that about 40 per cent of multi-manager hedge funds now have at least some money with external managers, and for now it hasn’t come at a cost to performance (zoomable version).

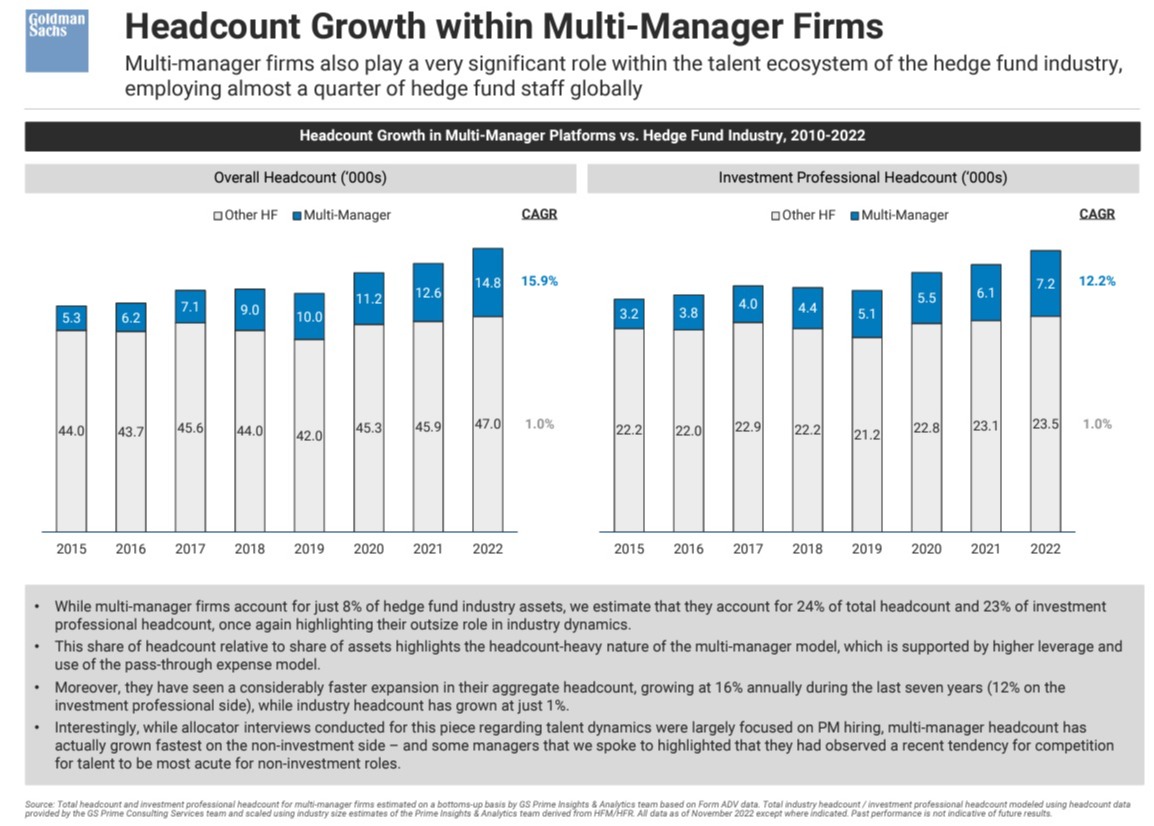

Another fascinating titbit we hadn’t previously appreciated is just how wildly manpower-intense multi-manager firms are compared to the rest of the industry.

While they account for only 8 per cent of the broader hedge fund industry’s assets, Goldman estimates that they account for 24 per cent of overall headcount.

That means that at the bigger multi-manager shops (with AUMs north of $10bn) the ratio of headcount to AUM is about $35mn, compared to $473mn at other hedge funds (zoomable version).

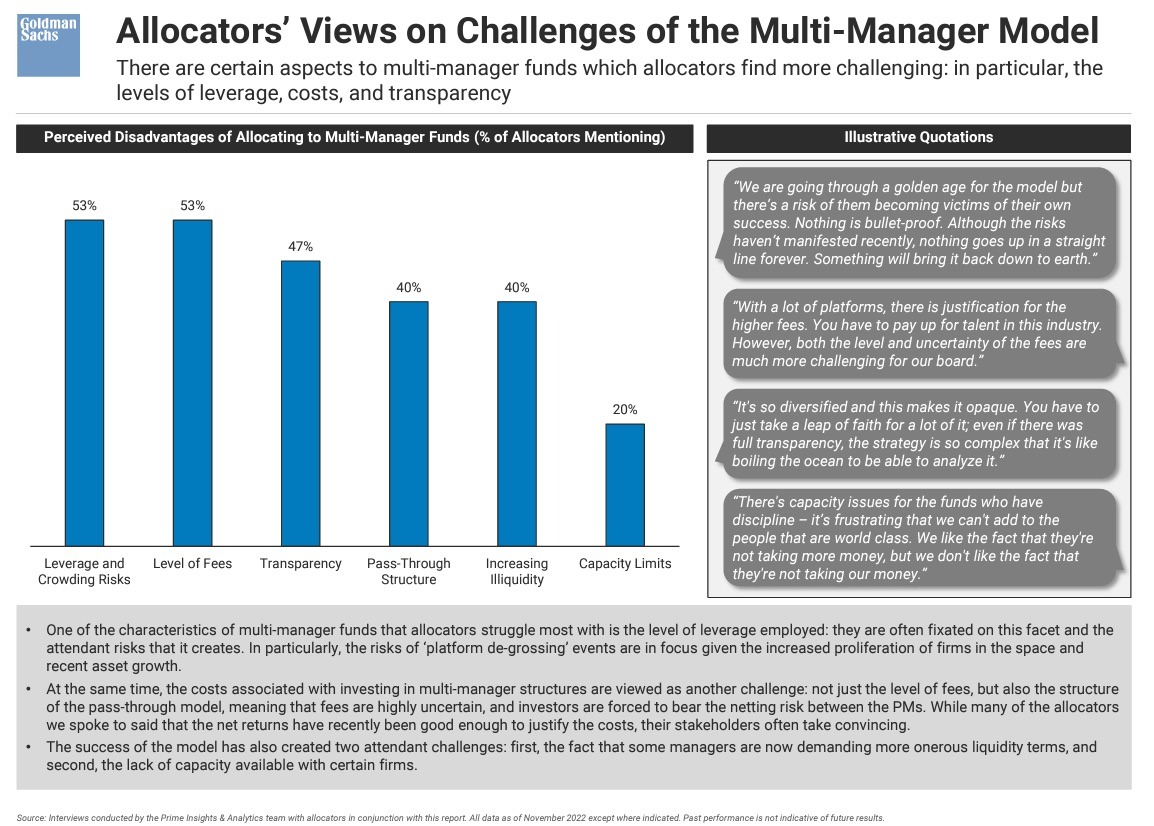

The Big Read does a great job of looking at the downsides and dangers, such as the risks of crowding, leverage, alpha decay etc, and to be fair to them, investors aren’t blind to this either.

Here are the main concerns that allocators mentioned to Goldman’s prime brokerage team. Interestingly, pass-through fees is a smaller worry than the fact that there might be nasty accidents. The sample quotes from allocators on this slide are also fantastic (zoomable version):

That all seems correct to us here at FTAV Towers.

Pass-through fees might seem egregious, but as long as the performance is good enough, who really cares.

The REAL worry is correctly that these funds are huge, unusually opaque, heavily leveraged and employ very similar strategies implemented by teams of traders and portfolio managers who often bounce from one firm to the next.

As a result, even if, say, a Citadel or Millennium has God-level risk management skills and Satan-level capital lock-ups, it’s easy to envisage a scenario where a smaller, less adept multi-manager hedge fund trips up, and that small snowball causes an avalanche across the industry as it deleverages and dumps positions similar to many other firms in the space.

Read the full article Here