9/11 ‘miracle’ babies, now turning 21, were lifesavers for families

These “miracle” babies are all grown up — turning 21 and reflecting on their solemn birthday, Sept. 11, 2001, when they saved their dads’ lives.

The babies were busy being born that tragic morning, ensuring that their fathers would not be in their downtown offices at the heart of disaster.

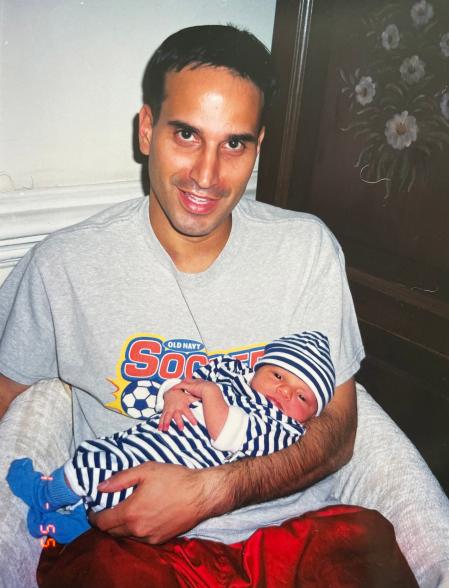

Instead of crossing the bridge connecting the World Trade Center to his CIBC Oppenheimer office at the World Financial Center, Steve Condos was at NYU Medical Center with his wife, Marika, who went into labor three weeks early. Their son, Reggi, was born at 9:23 a.m. — 36 minutes before the first tower collapsed.

It was “bittersweet” for Steve, who described the “juxtaposition of the circle of life, fighting through the happiness and sadness of that day.”

“He’s the reason I believe in miracles,” Marika said of Reggi.

“The timing was miraculous. Steve would have been at work,” said the West Village mom of three. “Most people start to cry. They say, ‘Oh my gosh, he most likely saved your husband’s life.’”

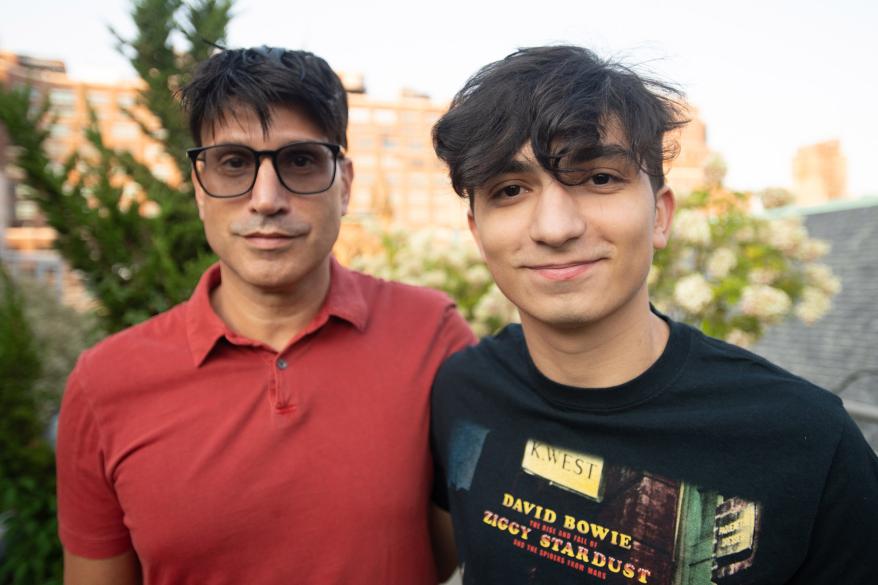

Being born on 9/11 is a “very significant part of my identity,” said Reggi, now a junior at NYU studying music.

When his parents first showed him the original Post story about his entrance into the world, Reggi, who traveled home from the hospital at three days old with a police escort, internalized conflicting feelings.

“It always gave me this feeling of how precious life is — that anything can happen at any time, and you should always enjoy life to the fullest while preparing for anything to happen,” he said.

Being born on such a fraught day is ”something that I take with me everywhere,” Reggi said, adding that as a kid he would spend time at a downtown firehouse near his old school studying the memorial to its bravest lost that day.

Reggi will spend his 21st birthday with his loved ones, but said, “It’s not just a normal birthday. Everyone celebrates their birthday the same way, but I have a different relationship with my birthday. I found my own ways to celebrate it.”

He also recognized that his story could have been very different, noting that many babies were born after their fathers perished in the terror attack. “We’re so grateful it worked out this way,” Reggi said. “It didn’t work out the same way for a lot of people”

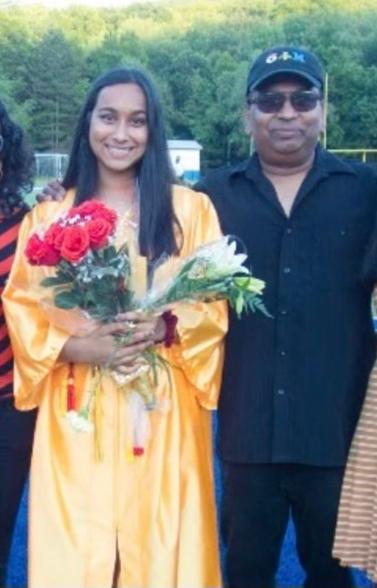

Gracie Silva, born six weeks early on Staten Island on 9/11, finds watching the annual memorial ceremony and reading of the names on TV a difficult dissonance of solemnity and celebration.

“It’s weird,” said the senior studying physiology at the University of Scranton. “Of course I’m sad, but it’s also the day I celebrate. But for so many people, it’s the worst day for them.”

Her mom Marylynne’s water broke in the pre-dawn hours that day. That meant her dad, Naveen, was by his wife’s side at the former St. Vincent’s Hospital in Staten Island, instead of heading to work as a computer technician at American Express on Liberty Street.

His normal commute would have had him passing through the WTC around 8:46 a.m., the time the first plane tore into the North Tower.

“I’m really close with my dad — he considers me his good luck charm,” said Gracie. “Whenever he has something important coming up, he always asks me to be there.”

“We are very religious and we believe everything happens for a reason,” said Marylynne, a Roman Catholic. “Maybe it saved his life. He would have been there.”

With some 150 babies born in NYC’s major hospitals that day, some light peaked through on one of the darkest days in the nation’s history.

“So many people lost their loved ones, it’s nothing to celebrate, but she represents new life,” added Marylynne. “It’s the only good thing about that day.”

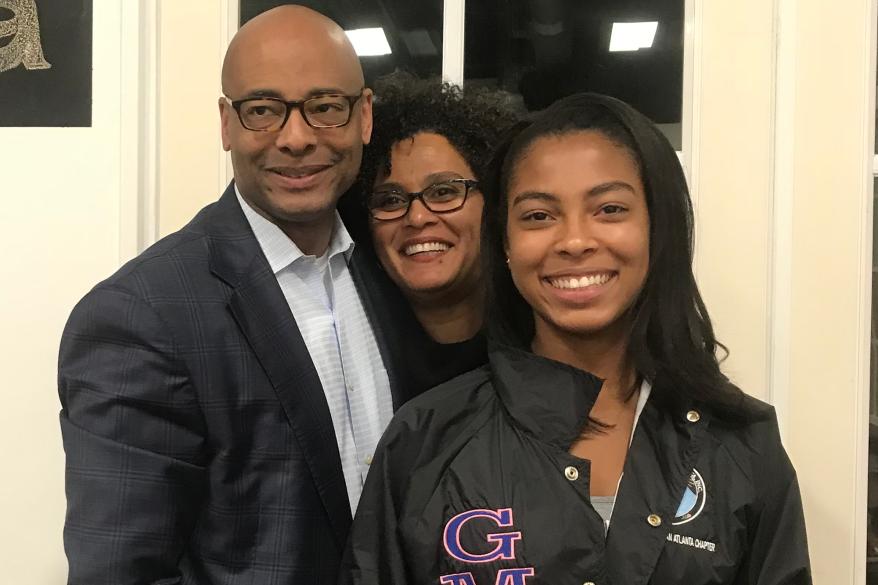

Aaren Evans also arrived on 9/11, nine days earlier than expected.

Her birth meant that Arnold Evans, then an investment banker at JPMorgan Chase downtown, was getting acquainted with his hours-old daughter at NYU Medical Center in Midtown, rather than heading to the office when tragedy struck.

“Sometimes I look at her and I wonder, ‘What did you come here to tell us?’ I believe she saved her father’s life — you never know where he could have been,” her mom, Joyce Evans, told The Post before her daughter’s first birthday in 2002.

“Every year on my birthday we have a conversation about it,” said Aaren, now a junior at Barnard College. “It’s always been an open thing – we talk about it.”

For Reggi, being a 9/11 baby means his connection to the city is unbreakable. “I feel like I’ll always want to be in New York forever. The city is part of who I am and my story.”

Read the full article Here