How Kim’s Video in NYC became tied to the mafia in Sicily

For nearly 30 years, Kim’s Video and Music, across five downtown locations, was a haven for NYC movie lovers offering a trove of 55,000 often rare, otherwise unfindable titles.

After the most famous location, Mondo Kim’s on St. Marks Place in the East Village closed in early 2009, the massive collection went on a wild journey all the way to Sicily, and even became tied to the mafia before finally making its way back to New York last year.

While filming his new documentary “Kim’s Video,” which recently premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, director David Redmon ventured to Italy on a quest to discover what really happened to the iconic inventory.

It’s a story straight out of a movie.

Kim’s Video started out modestly in 1987 by Yongman Kim as a VHS-tape rental shelf in a corner of his dry-cleaning store put up to make some extra cash. Soon, the rental business was eclipsing the pressed shirts, so he expanded to a full video and music shop on Avenue A, and quickly became known for curating esoteric titles.

“Stepping foot into this video store was, ‘Wow. I’m stepping into the goldmine of cool,’ ” said David Wain, director of “Wet Hot American Summer” and a former Kim’s Video member.

Eventually, Kim’s amassed more than 250,000 members, and to keep his offerings bold and fresh, he would send employees to far-flung international film festivals to secure unreleased movies. Sometimes, he’d get VHS tapes from foreign embassies in New York, make a copy, and stick it on his shelf.

The FBI and local authorities repeatedly raided Kim’s in the aughts, accusing the store of piracy.

“The counter was right in front of the racks of bootleg VHS tapes, and we’d watch these guys in suits take out these bags and clear out rows and rows of VHS tapes,” former employee Ryan Krivoshey says in the doc.

Kim would come back a week later, with new copies of the confiscated movies in tow, and put them right back where they were.

Due to the rise of streaming services like Netflix, Kim eventually closed his last shop on First Avenue in 2014. Famed directors the Coen brothers allegedly had a $600 late fee, which was never paid.

Back when he was closing his St. Marks flagship, Kim sought to unload the thousands of films to a person or entity who met specific criteria: that they had at least 3,000 square feet of space, allowed Kim’s Video members access to the films and kept the collection in good condition.

Oddly, Kim picked the town of Salemi, Sicily.

“How could anybody think for a second that sending this entire thing to another country — even though they say, ‘Well, any members who walks in the door is welcome to access the collection? What on earth could someone have been thinking that this to them made more sense than NYU saying, ‘We will take it?’ ” says an employee. “As legend has it, those were the options he was faced with.”

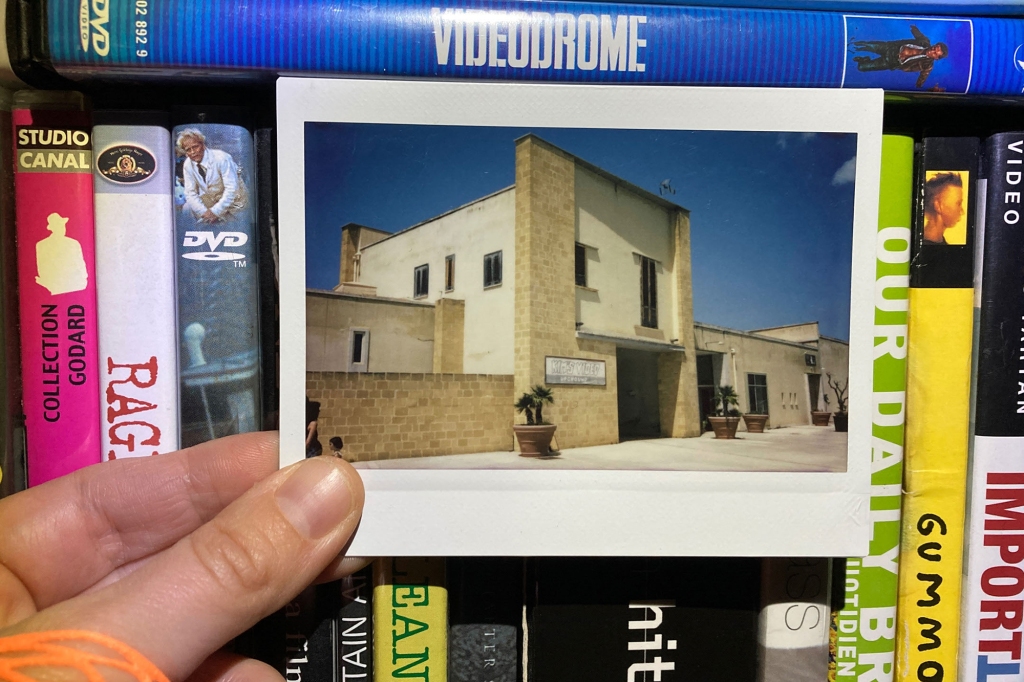

The employee’s concerns were correct. When Redmon traveled to Salemi more than a decade later, he discovered that the room housing Kim’s Video — locals call it “Centro Kim” — was inaccessible to the public, in poor shape and filled with film-damaging moisture. A promised digitization of the collection never occurred.

Mayor Vittorio Sgarbi had initially angled for Kim’s videos in hopes of turning Salemi, which was destroyed by an earthquake in 1968, into an artist colony. But the politician and art critic, who later became the right-hand man of President Silvio Berlusconi, was removed from power in Salemi for allegedly allowing the mafia to infiltrate his cabinet. Kim’s got caught up in the corruption.

Journalist Marco Bova says in the doc that the accused government mafioso, Pino Giammarinaro, “controlled a huge budget of 800,000 euros that was supposed to finance different projects, not only the digitization of [Kim’s] collection. [Yet] only 30,000 euros were spent without producing anything.”

Appalled by what he saw, Redmon tracked down Kim, who still owns a home in New Jersey, to Seoul, South Korea, and informed him of what had happened.

“That part, I’m a little regret[ful],” Kim says. “Because Sgarbi was an issue, a legal issue there. A criminal issue.”

So, Kim visited Salemi and expressed his dismay.

“I’m very sad that it’s not properly stored, and it’s not properly managed,” he says, adding that they were “not using it for the public and the people.”

Shockingly, Redmon then stole the tapes in the dark of night — under the guise of using the facility to make a short film — and shipped them back this past April to New York to the Alamo Drafthouse in lower Manhattan, where some 20,000 are now available to rent for free.

Redmon and Kim negotiated with spurned Salemi and agreed to a few conditions to avoid retaliation, including giving several members of the government an all-expenses-paid trip to NYC where Kim would thank the town during a press conference, and advertising Salemi tourism at the new brick-and-mortar Kim’s Video downtown.

“Salemi contacted me and wanted to know what happened to the movies,” Redmon said in the doc. “I told them, as a former member of Kim’s Video, I just checked out a few movies for my friends.”

Read the full article Here