Flawed musical gets heartfelt revival

The greatest asset of the Broadway revival of “Parade,” Jason Robert Brown’s sorrowful if flawed musical about the 1915 anti-Semitic lynching of Leo Frank, is youth.

Playing husband and wife Leo and Lucille Frank, Ben Platt and Micaela Diamond come across strikingly young (and at 23 years old, Diamond really is), like a faded photo of your great-grandparents that you discover in a drawer. The subjects neither smile nor frown, but behind their neutral stares is so much promise and fear.

2 hours, 30 minutes, with one intermission. Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, 242 W. 45th St.

Those clashing forces are what drive this revival, which opened Thursday night at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, and make the audience automatically want what’s best for Lucille and Leo — even though we know that a peaceful life is tragically out of reach for them.

That we care about their future is a vital layer for an often cool-to-the-touch show that has always been more concerned with the issues it confronts rather than the people it’s about.

Truth be told, “Parade” is a musical that will forever be good rather than great — hampered by writer Alfred Uhry’s book of stereotypical Southern cartoons, who are made less menacing and real because of their flatness, and a score by Brown that features both his best songs and his most forgettable.

But director Michael Arden’s small-scale staging, which started as a City Center concert, has heart when it focuses squarely on the Franks’ relationship growing while their hardship intensifies.

The show starts and ends with a lush and loud number called “The Old Red Hills of Home,” partly set during the Civil War and partly in 1915, suggesting that stubborn Southern pride — undeserved, in this show’s estimation — is ongoing and unchanged.

Leo has just moved from Brooklyn to live with Lucille in Marietta, Georgia, where she’s from, and he feels out of place as a Jewish man — even among Southern Jews. “I thought that Jews were Jews, but I was wrong!” he sings.

And he’s right to feel targeted. While working as a manager at the National Pencil Co., he’s arrested on suspicion of killing a teenage employee named Mary Phagan (Erin Rose Doyle), whose body is found in the building. There are other suspects, but the authorities willfully ignore them and go after Leo.

It’s those authorities — as written, and resultingly performed — who drag “Parade” down with hackneyed, barked dialogue. The racism-spewing lawyer Hugh Dorsey (Paul Alexander Nolan) and newspaper reporter Britt Craig (Jay Armstrong Johnson) are particularly one-note on paper.

They seem fake, but pictures of the real historical figures are projected throughout the production onto the back wall and sometimes in the middle of a song, which is an unnecessary distraction.

Brown’s finest music, and Platt’s most heart-wrenching work, come during his trial, as three factory girls (who have been coached to lie) hauntingly harmonize their testimony like Abigail from “The Crucible.” Brown has yet to top it in any show.

When Leo gives his statement, and Platt sings that his character is unemotional and awkward but innocent, it’s the tears-free opposite of when he sobbed at the end of “Dear Evan Hansen,” but the gut-punch is the same.

The second act has more built-in structural issues, as Lucille works tirelessly to appeal her husband’s verdict and enlists the help of Governor Slaton (Sean Allan Krill) to get Leo home. A galvanizing number is followed by minutes of aimless procedural wading. But there are few sublime moments.

As another factory worker, and suspect, Jim Conley, Alex Joseph Grayson wails the song “Feel the Rain Fall,” which is gorgeous but pops up out of nowhere.

And Diamond, whose combination of fragility and power is thrilling for an actress so young, brings an electricity to her duets with Platt: “This Is Not Over Yet” and the romantic “All the Wasted Time,” which fades into the musical’s devastating conclusion.

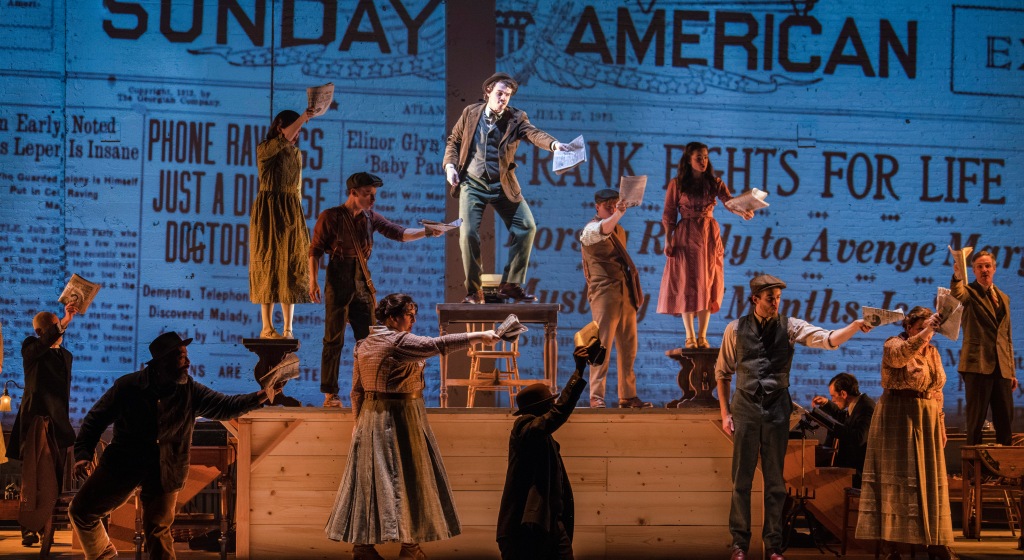

While Arden’s production is admirably (and predictably) intimate, the centerpiece of Dane Laffrey’s set — a raised wooden platform that looks like something you might find on a parade route, or at an execution — is a roadblock.

Audience members in the front orchestra have to crane their necks to watch many of the scenes atop the monolith, and actors are forced to go up some stairs to inhabit the strongest points on the stage. That the whole cast sits onstage observing the fate of Leo was a tad too obvious and spatially limiting. For me, the structure only takes away — it never contributes anything.

Still, Arden has directed a tender production of a musical that can often play like a sledgehammer, and has an anti-hate message that’s distressingly relevant.

Read the full article Here