Marine vet puts military logistics to work with launch of NYC pot home delivery service

He still adheres to the Semper Fi motto.

Retired Marine Osbert Orduna runs the metro area’s first licensed home delivery cannabis service from a small base in Queens — vowing to faithfully deliver legal weed right to your doorstep..

Orduna, 48, is also the first disabled vet to open a state-approved marijuana sales business through his newly opened firm, The Cannabis Place.

“We’re the first to open. More vets are coming,” he said.

The son of Colombian immigrants was among the first wave of Marines involved in the 2003 US invasion of Iraq that deposed dictator Suddam Hussein.

The Queens native supervised a 90-member unit responsible for disabling bombs and checking on biological and chemical weapons on the battlefield, and also oversaw convoy security responsible for protecting supply lines.

He’s now putting that logistical knowledge to use in his budding pot delivery business.

“A lot of our suppliers were unarmed contractors who needed protection,” he said.

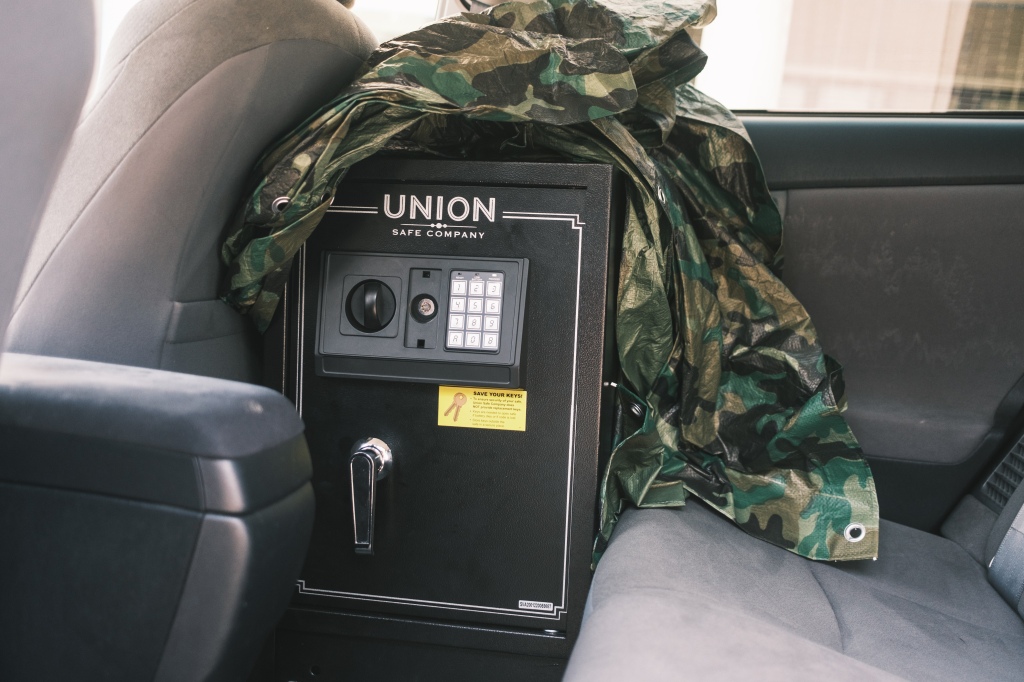

A Post visit to his “base” found a sophisticated set-up with extensive surveillance and GPS technology integrated into the entire operation — not unlike those used by the military, law enforcement and delivery app services like Uber and Lyft. For safety reasons, there are no signs from the exterior that a weed delivery system has set up shop there.

Four of the seven workers he’s hired so far are military vets.

“We leveraged our skill sets in the military for the cannabis delivery operation. We have a robust readiness communication and dispatch system similar to what we used in Iraq. We have constant communication for safety during deliveries,” Orduna said.

“We can communicate live at all times. Everything is under surveillance. We’re leaving the base to make deliveries. It’s a parallel to what we did in the military.”

All deliveries are tracked in real time using the company’s own GPS system to route drivers depending on traffic. Customers get a text message when a delivery is nearby. Payments are made online by customers — via ACH venmo — and there’s no cash exchange. Customers will soon be able to pay directly with a debit and credit card.

“There’s no handling of cash in the field,” he said.

The customer base for deliveries is mostly middle aged and older — with even an 81 year old ordering edibles, according to tracking profiles.

“There’s a lot of moms and dads professionals and attorneys wanting to manage stress and anxiety. Our purpose is to make high quality licensed cannabis accessible,” Orduna said.

Deliveries are made in Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan and Long Island — with about half in Nassau and Suffolk counties.

Under the law, local communities can refuse or opt out of approving pot stores in their neighborhoods. Nassau County has completely opted out of selling cannabis in storefronts, as have most of Suffolk Count’s towns.

But residents can order cannabis brought directly to their home, providing massive business opportunities for delivery services. The Cannabis Place doesn’t charge a delivery fee.

“Our purpose is to make high quality licensed cannabis accessible,” he said.

Customers appreciate the convenience of the home deliveries, driver Edward Bailey, 68, who served in the Army in post-Vietnam war era, told The Post.

“They say, `Thank you, thank you.’ They don’t have to go out and get it,” Bailey said of the happy faces he sees when he arrives with their bags of cannabis goodies.

There’s a minimum $150 purchase of cannabis products for home delivery. The average order is $300 though some people have ordered more than $1,000 of weed or other THC-infused products, Orduna said. Same day or next day deliveries can be made from noon to 8 p.m., seven days a week

Under state law, all New York cannabis products must be lab-tested.

Orduna relies on a network of 26 different regular cannabis users he knows to sample all the products — including weed, vapes, edibles, beverage and ointments. The graders fill out a questionnaire and rate the products on a scale 1 to 10.

Orduna, who grew up in the Woodside Houses, joined the Marines in 1994, seeing it as “an opportunity to get away from the neighborhood.” And marijuana was part of life in the projects and neighborhood growing up, he said.

When he left the Marine after 10 years, he noticed vets who suffered from PTSD were given addictive prescription opioid drugs like oxycodone. He said he knew a few who committed suicide.

“It’s chemical sh*t. It’s poison in a bottle. They came back home and were walking zombies. Opioids stole their lives,” he said, noting his own experience of the drug after surgery. “I was in the twilight zone. It’s not good for you.”

Orduna became interested in marijuana as a mellower and less addictive alternative for disabled vets around the time New York approved the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes via prescription in 2014.

The legislature and former Gov. Andrew Cuomo legalized the sale of marijuana for recreational adult use in 2021, though the rollout has been slow and rocky while a huge illicit market of pot stores has proliferated, drawing the ire of New York City Mayor Eric Adams.

The Marine vet visited 50 small or independently owned cannabis shops in five other states to learn more about the cannabis industry.

Orduna said he works closely with the “justice involved” in the cannabis industry who were convicted of marijuana-related crimes when its possession was outlawed — and claims minorities were “collateral damage in the war on drugs.

Disabled vets under the law are eligible for cannabis licenses. But those convicted of cannabis offenses were among the first to be given licenses to right the wrongs of that war, Gov. Kathy Hochul and state regulators said.

Though preference to ex-cons over vets stirred resentment, Oduna pressed ahead, partnering with Khaled Ahmed, general manager of The Cannabis Place, who was incarcerated for selling marijuana when it was outlawed.

Orduna said others who are disabled have gotten licenses to operate cannabis retail dispensaries but are looking for space to locate their stores, a persistent problem that has slowed the rollout. There are only a dozen retail dispensaries operating throughout the state, including seven in New York City.

Read the full article Here