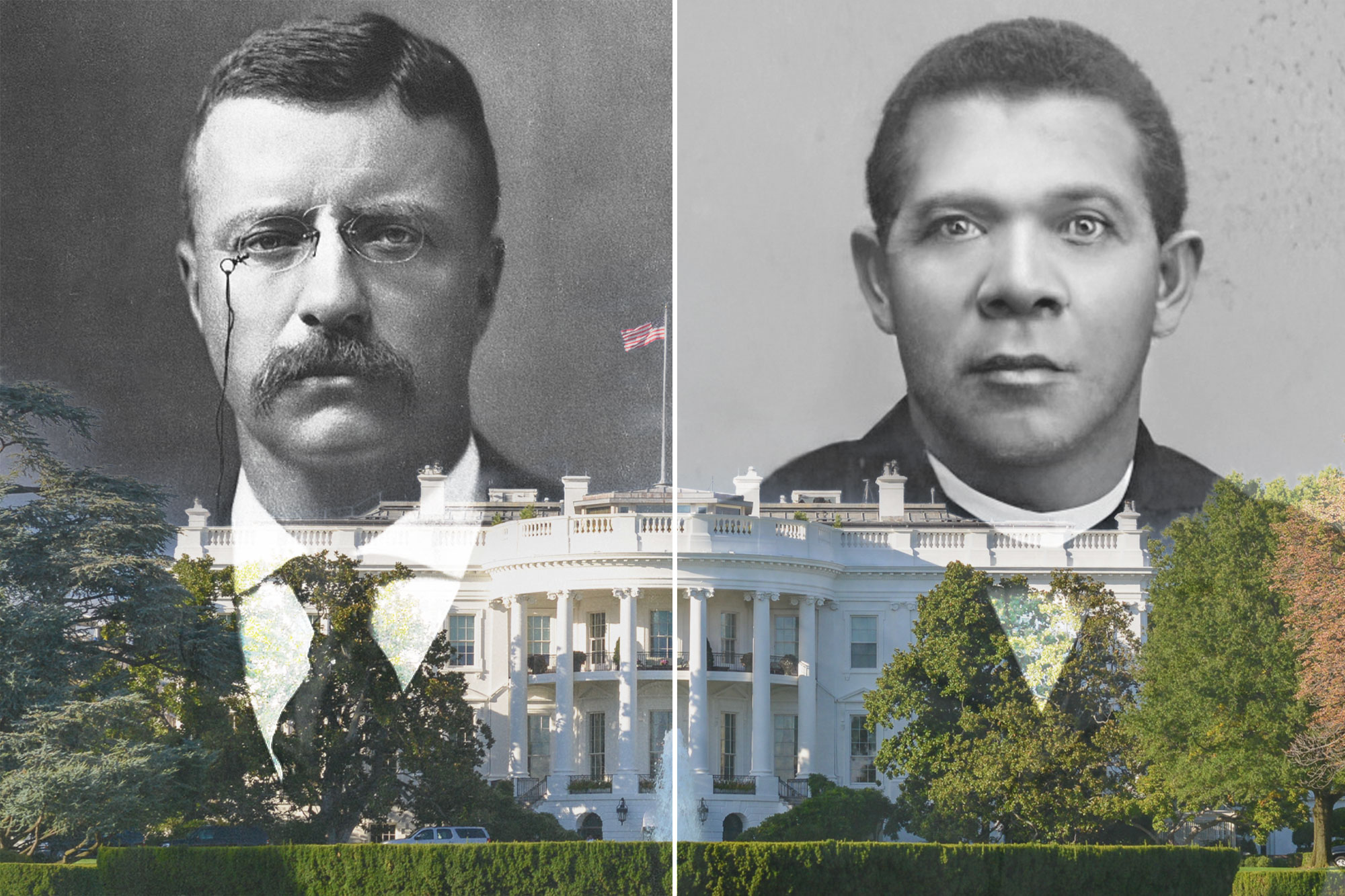

Teddy Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington’s dinner changed history

In his new book, “Teddy and Booker T: How Two American Icons Blazed a Path for Racial Equality,” bestselling author Brian Kilmeade writes of how Theodore Roosevelt invited intellectual and former slave Book T. Washington to dinner at the White House at the very beginning of his presidency. Roosevelt sought Washington’s counsel as he struggled to steer the country — and especially the South — forward in the wake of Jim Crow laws and racial violence. Here, an excerpt:

On the evening of Thursday, Oct. 16, 1901, Booker T. Washington and Theodore Roosevelt dined in the Executive Mansion with the first family. High spirits prevailed; however, in this circle of Roosevelt’s family affection and friendship, Washington was a stranger. When dinner finished, Roosevelt and Washington retired to discuss the South and government appointees at length, and Washington left to catch a night train to New York.

As the train rumbled north, Booker T. Washington was acutely aware that, for the first time in the nation’s history, a black man – and one who had been formerly enslaved – had broken bread at the nation’s first table. While such thoughts must have elevated Washington’s spirits, his anxiety about the risks of this moment surely weighed them down.

Perhaps his mind went back some weeks before, to the day he received a letter from the brand new president that set this historic event in motion.

On Sept. 14, 1901, following the assassination of President William McKinley, Teddy Roosevelt was sworn in as the 26th president of the United States, and vast new responsibilities had fallen into his lap. Roosevelt recognized he now possessed the power to engineer change in America, but he also felt a new obligation to be prudent: With the eyes of the world suddenly on him, he had to proceed with care as he took the country’s reins, balancing his instinct to bull forward with a mindfulness of potential risks.

Roosevelt, anticipating a future presidential campaign, wanted more than ever to develop stronger ties in the South. He was still in Buffalo, when, on the afternoon of September 14, 1901, he composed the one letter that he sent on the day he took office. The addressee was Booker T. Washington, Esq., Tuskegee, Alabama.

In his first week in the White House, while the nation mourned the loss of a President, Roosevelt began to fill jobs with the best and most qualified men – and when it came to the South, he had decided there was no one better to consult than Booker T. Washington. Additionally, he saw their meeting as a chance to address the volatile subject of race. Booker was uniquely positioned to help identify the best men in the South, Republican or Democrat, black and white. He was a man whose entire adult life had been consciously, intentionally, and rigorously apolitical.

During their initial late-night meeting, the new president proposed putting good men of color into offices in the North, a nearly unprecedented promise. Booker left this meeting with Theodore buoyed with hope. With Washington’s guidance, jobs could be filled with men who genuinely believed in the rights of black people.

Booker’s optimism, however, was tempered by Roosevelt’s practicality. He was also aware that Roosevelt, like all but a tiny minority of white Americans, regarded Africans as both inherently inferior and a race disadvantaged by enslavement. But this direct access to presidential power was extraordinary – and any improvements of the rights, even if slow and incremental, would be welcome.

In the days that followed, Washington wrote a series of letters of reference for other candidates for Federal appointments, black and white. This was a real chance to change things: for years, the federal government had consistently taken a hands-off approach in Southern states, but this could signify a shift in momentum. Washington and Roosevelt’s quiet, behind-the-scenes collaboration was working well. But after their next meeting – over dinner at the White House on Oct.16 – much would change.

Even before Booker reached home in New York, news of his dinner with Roosevelt was spreading. Reactions appeared in papers across the country. A few were fair but most of them foul – with the Nashville American calling the White House dinner “an error of judgment and a breach of good taste.” And the anger continued to escalate. The story assumed a power all its own, inspiring journalistic imagination and a simple supper had become a reminder of how deeply divided the nation remained almost four decades after emancipation.

Roosevelt sent word to Washington via a private channel that he “did not care…what anybody said or thought about” their evening together. He told another friend that despite the damage done, he would not bow to the pressure and distance himself from Washington. But Roosevelt couldn’t quite put the episode behind him as the papers continued to debate what had happened. That their connection was now national news meant that, in the eyes of some Southerners, Roosevelt had committed a double sin. As if dining with a black man wasn’t damning enough, Roosevelt was clearly taking Washington’s advice concerning appointments, and, some believed, even allowing a black man to help shape national policy.

Years later, Washington broke his long silence concerning the White House dinner in a book, “My Larger Education.” A decade had passed, and he waxed philosophical about “the curious nature of this thing we call prejudice.” Always the realist, Washington knew he could not change the thinking of many, illogical though it might be. From harsh experience, Washington wrote, “I have come to the conclusion that these prejudices are something that it does not pay to disturb. It is best to let ‘sleeping dogs lie.’”

The fallout from the dinner, at least as Roosevelt had interpreted events, set new limits on the interactions he might have with the man from Tuskegee. If he wanted to win the presidency in his own right in 1904, Roosevelt realized, he could never again invite Washington or any other black man to dine at table (“What I did was a mistake,” he acknowledged years later). The political risks were too great; Mark Twain and countless others had told him that. Thus, Booker T. Washington made his first and last appearance on the White House dinner table on October 16, 1901. Only time would tell what would be the larger impact of the White House supper on the hopes of black Americans.

“This excerpt is adapted from “Teddy and Booker T: How Two American Icons Blazed a Path for Racial Equality” by Brian Kilmeade with permission from Sentinel, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC copyright © 2023 by Brian Kilmeade”

Read the full article Here