Inside the dangerous world of professional bull riding

When East Village-based PR expert Andrew Giangola was asked to represent Professional Bull Riders (PBR) in 2015, he felt like a fish out of water. “I’m a New Yorker. I ride a subway, not a horse,” he told the Post. “Suddenly, I found myself surrounded by cattle and guys named Cody and Chase. But as soon as I went to my first event, I knew it was for me.”

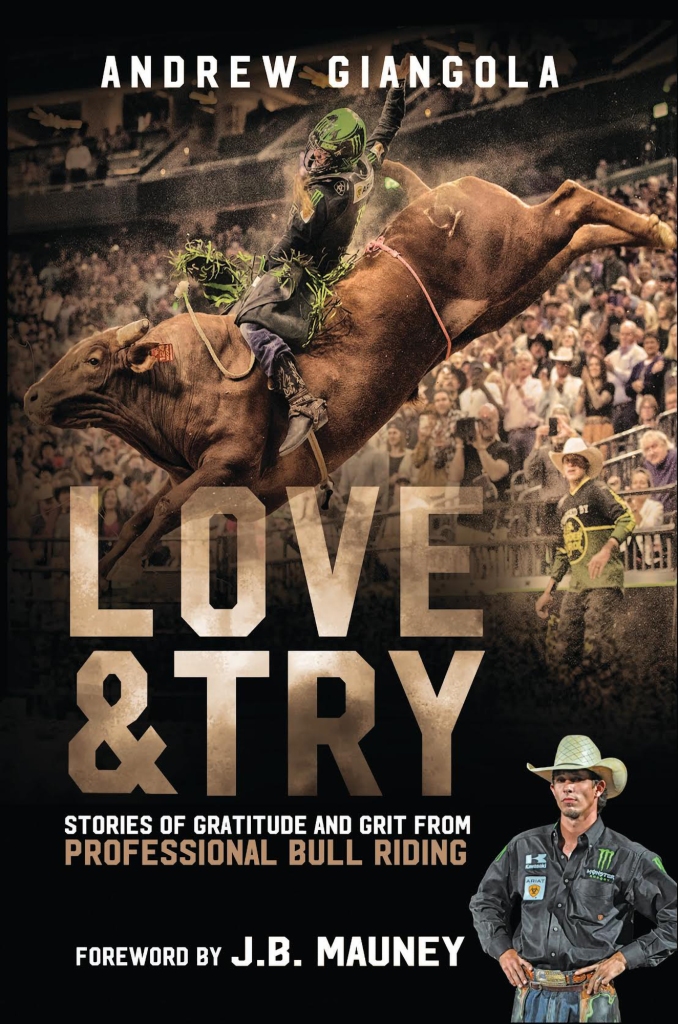

As an urban outsider, Giangola suddenly had a front row seat to one of the world’s most dangerous organized sports. Riders — who don’t get paid unless they stay on the bull for at least eight seconds — are regularly bucked and sometimes severely injured. “In the background is the constant specter of palpable danger,” he says. “The whole experience is intoxicating.”

While visiting the bull riders on their traveling tour, Giangola began scribbling wild anecdotes and cowboy quotes down in his notebook. It wasn’t long before he realized he had a book on his hands. And so “Love and Try: Stories of Gratitude and Grit from Professional Bull Riding,” an “all-American celebration of faith, freedom and country,” was born.

The true focus of “Love and Try” is the people behind the sport. Giangola tells the stories of around 30 employees of PBR — including the bull riders themselves, the people who raise the bulls, the rodeo doctor, and the guy who brings in the dirt that covers the ring floor.

“There are so many worthy characters in this sport — plainspoken, hard working men and women who have a gritty, refreshing can-do attitude,” he says. “I hope readers end up falling in love with these people just like I did.”

Take the story of Jerome and Tiffany, for instance. When they were a young couple, Jerome was thrown on his head by a bull and instantly paralyzed. While in hospital, the doctor told him it was inevitable that his new girlfriend would leave him. And yet, decades later, they are as in love as ever, with a family and a farm where they raise bulls together.

“They raise them like their children,” says Giangola. “Animal care is such an important part of the sport, and I wanted to disabuse people of the common misconception that the bulls are mistreated.” In fact, while the average bull raised for food is slaughtered by age 3, bull riding bulls often die naturally on the ranch after retiring from competition.

More than anything, Giangola, who is donating his proceeds to pay the medical bills of injured riders, wanted to share the sport’s grit with readers. “Riding is the lens, of course, but this is really a book about values,” he says. “I hope readers end up falling in love with these rugged, resilient, hard working people — and I think America wants and needs to rediscover those values.”

Read the full article Here