Texas veteran shot down in Vietnam on 7 years as POW at ‘Hanoi Hilton’ prison camp: ‘You keep faith’

Five decades ago, Col. James Lamar was playing poker against fellow prisoners of war with cards made of toilet paper and chips made of matchsticks at the “Hanoi Hilton” in North Vietnam on the tail end of his nearly 7-year stint at the notorious prison camp.

Today, 94-year-old Lamar enjoys playing Texas Hold ’em against a rotating cast of college students, tech bros, retirees and fellow veterans who frequent Texas Card House in the state capital of Austin.

Lamar detailed the day he got shot down in Vietnam and his experience as a prisoner of war in an interview with Fox News Digital at the card house.

Lamar joined the Air Force in 1948 after three years in the Naval Reserve and completed pilot training in 1949. He was deployed to a fighter squadron in Japan just before the Korean War broke out and flew 100 combat missions in that conflict in 1950-51.

WORLD WAR II’S D-DAY: PHOTOS REVEAL WORLD’S LARGEST AMPHIBIOUS INVASION

After returning from Korea, Lamar served in various pilot instructor roles before deploying to Thailand at the start of the Vietnam War.

“When we got the news that we were going to go, I got an immediate premonition that something was going to happen to me — I would be shot down, killed, prisoner — I didn’t know what, but I knew something bad was going to happen,” Lamar said.

Sure enough, on Lamar’s 101st mission in North Vietnam on May 6, 1965, he was shot down during a bombing run over a railroad yard.

“We got to our target area, I was the first one to go in,” Lamar said. “I pulled up to 12,000 feet, rolled over, and when I was headed down, I would like to have been some place else, because the flak (anti-aircraft fire) was just a solid layer below me. As I dive through it — boom — I got hit, my plane got hit in the fuselage forward of the cockpit, but there was an immediate fire in the cockpit.”

D-DAY WAR HERO DIES ON INDEPENDENCE DAY AT 99 YEARS OLD

Lamar pulled out of his dive and started jinking side-to-side to avoid further anti-aircraft fire, then radioed his team to tell them that he was heading to a safe bailout area about 50 miles away.

“Immediately after I said that, there came the very excited voice of my No. 4 man, who yelled at me, ‘Get out, lead, you’ve got a big fire going,'” Lamar recalled.

“So I just reached for the handles … the left one, the canopy went, and the right one, I went. One problem, the handbook on the aircraft said do not eject over 525 knots, nautical miles per hour. If you do, all sorts of bad things can happen. Well, the last time I saw the airspeed tape, just before I left that cockpit, it was going rapidly through 700 knots. So I ejected at above the speed of sound.”

LAST REMAINING WORLD WAR II MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENT TO LIE IN HONOR AT US CAPITOL

Lamar woke up with a broken arm and his parachute hanging from a tree. A group of Vietnamese peasants eventually found him and took him to a military post to turn him over to the North Vietnamese army, which tortured him and tried in vain to get Lamar to lure other fighter pilots into an ambush.

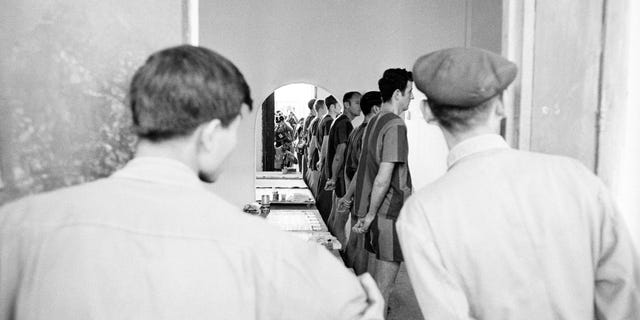

After failing to get any information out of Lamar, the soldiers took him to Hỏa Lò Prison, which Americans prisoners of war facetiously called the “Hanoi Hilton,” where he would spend nearly seven years.

During the first few years in the prison camp, his captors subjected him to various degrees of mental and physical abuse, but the Americans figured out that they could safely communicate around lunchtime when the guards took a break.

“One day in our noon communication, I told the guys that I’m very depressed. What do you do to combat depression? Jerry Denton (another prisoner of war) said, ‘I’ll tell you what you do, Jim. You pray. You keep faith in God, your country and your family. And then you live each day, one day at a time. That’s the way you get through,'” Lamar recalled.

“And he was right. My depression lifted, and I started living one day at a time. And that’s how I went through the total 2,400 and some odd days.”

Lamar was eventually released Feb. 12, 1973 with several hundred other prisoners of war in Operation Homecoming.

Read the full article Here