The Excruciating Echo of Grief in Uvalde

The community buried 21 people after the Robb Elementary School massacre. In the weeks that followed, the aftershocks only compounded the agony.

A makeshift memorial in front of Robb Elementary School grew quickly in the days after the shooting.

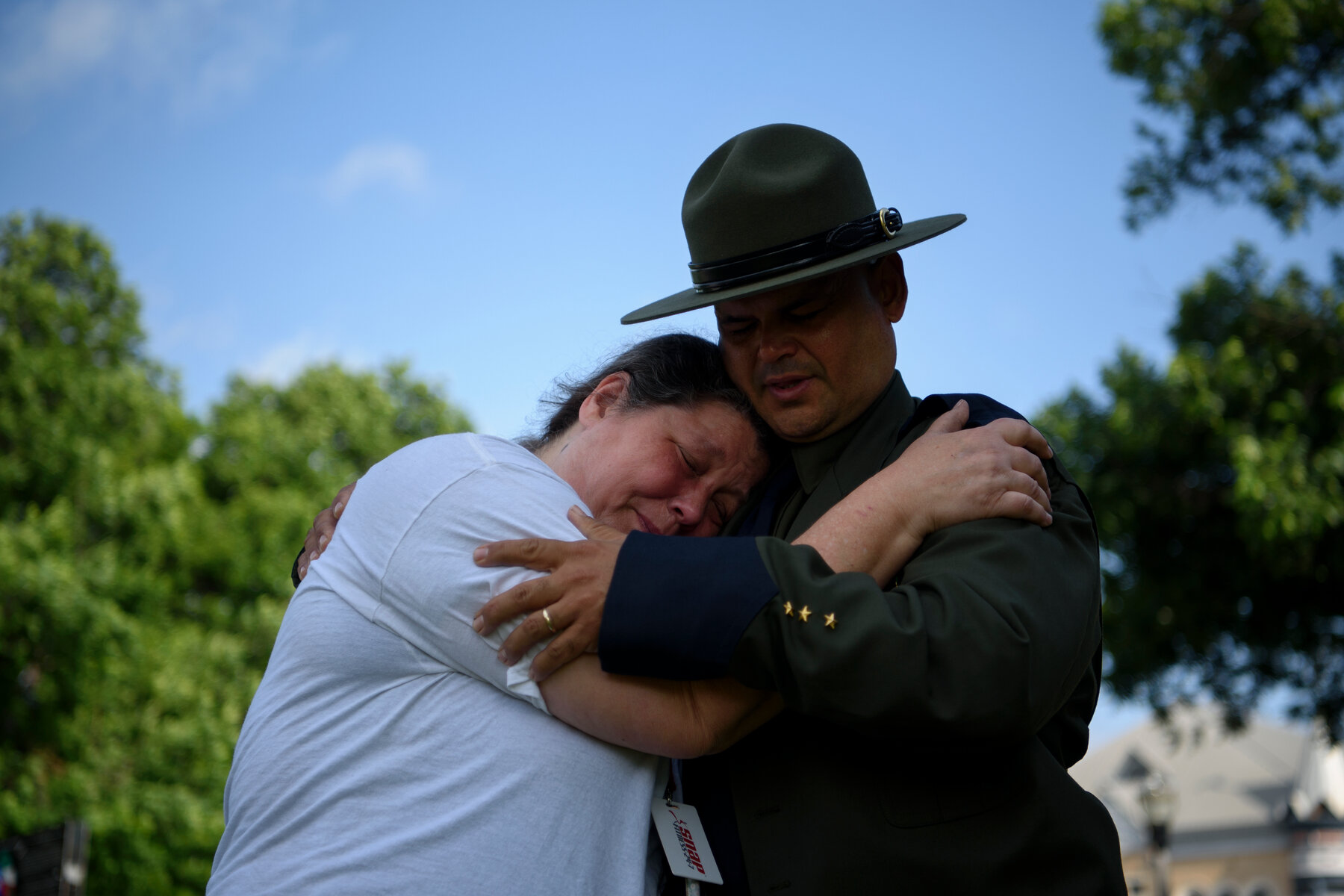

A group of people embraced after a news conference at Uvalde High School.

Uvalde residents and family members of those killed in the Robb Elementary School shooting march from the school to Uvalde’s town square.

Nikki and Brett Cross, the guardians of Uziyah Garcia, 10, who was killed in the shooting.

Uvalde residents and people from across Texas release balloons during an event honoring the victims.

J.T. Martinez, 9, attended the funeral of Xavier Lopez, his close relative and best friend.

The graves for Irma Garcia, who was killed during the shooting, and her husband, Joe Garcia, who died of a heart attack two days later.

UVALDE, Texas — In a cemetery on the edge of Uvalde, a cluster of fresh graves had been carved from the parched, rocky earth. The dead were claiming new ground: No sod had been laid. No trees had taken root to shield against an unrelenting South Texas sun.

Uvalde had weathered loss, but never anything like this. The community had crossed into unfamiliar terrain, as the massacre at Robb Elementary School created a marathon of mourning that started with vigils in the hours after the May 24 attack and continued for weeks until the last victims were buried.

On June 3, Javier and Gloria Cazares buried their daughter Jacklyn in one of the graves. On June 8, they returned for the burial of their niece, Annabell Rodriguez. A few days later, on a Sunday evening, they were back again with Jacklyn’s older sister, Jazmin. They had just been to the visitation for another classmate who was killed. On their way home, they stopped to collect the balloons they had set out for the 10th birthday Jacklyn was supposed to celebrate on June 10.

“We lost a child,” Ms. Cazares said. “We lost all of her friends. Our friends lost children.”

“It’s so much.”

Part of the cruelty of what Uvalde endured lay in the repetition: One funeral after the next — days with one in the morning, another in the afternoon and then a visitation after that — into the summer. The pastor giving a variation of the same sermon, beseeching an anguished community not to let its anger ferment into malice. The collections of 21 crosses, one for each of the 19 students and two teachers who were killed, that sprouted all over town.

It was an excruciating echo.

It also reflected an enormous undertaking, as overwhelming emotionally as it was logistically, to memorialize the dead and care for those now living with debilitating loss.

Uvalde’s plight is as agonizing as it is familiar. The attack, now more than 10 weeks past, initiated the city into a crowded cohort of American communities forced by a gunman’s actions to navigate the long, brutal path that is the aftermath of mass violence.

Soon, just as in Newtown and Parkland and Sutherland Springs — other places indelibly associated with shootings — the path will splinter into countless trails, diverging as individuals wrestle with varying degrees of trauma and heartache, confront their own struggles and move at their own pace.

But for now, Uvalde is bound by its collective grief.

Dave Graham paid his respects as the funeral procession for Rojelio Torres, 10, drove by him. Mr. Graham came to Texas from Ohio to offer emotional support to members of the community. “I wanted to make a place for people where they could be safe,” he said, “where they could cry or they could yell or they could ask why.”

Uvalde hosted the Texas Little League District 21 All-Star tournament, where posters were hung honoring the players who were killed in the shooting.

A mourner at one of many makeshift memorials around Uvalde.

Uvalde’s town square was also turned into a makeshift memorial.

A Border Patrol agent hugged a community member at a memorial ceremony.

Xavier Lopez’s family had T-shirts made in his honor.

Matthew Villanueva, 10, of San Antonio, looks on as Michael Sanchez, a San Antonio artist, adjusts the placement of doves for a mural honoring the victims.

Uvalde is a small community of roughly 16,000 people, situated in the scrubby, wide open territory between San Antonio and the Mexican border.

The shooting has made it feel even smaller.

In some ways, that has been reassuring, a testament to the community’s cohesion.

But it has also been constricting. And in the immediate aftermath, a crush of outsiders swarmed into town: law enforcement officials, reporters and camera crews, politicians, evangelists, Meghan Markle, motorcycle gangs, people who came to help, and others who slowly drove through town, drawn by lurid curiosity — all creating a sense that Uvalde was stuffed well beyond capacity.

The crowds have largely retreated and the mountainous memorials have been consolidated. The void has been filled by a growing outrage, inflamed by revelations about apparently catastrophic miscalculations by law enforcement officials who responded to the shooting.

Uvalde is a beautiful, little loving town.

I went here to Uvalde High School,

and I met my sweetheart, Johnny Moreno.

We didn’t have any money to go on a date, so

we went to the Robb school playground.

We got married two and a half years later.

Y’all can take a bunch of stuff to the hospital too, OK.

Once they started naming the children,

people were sending flowers to the school,

to the memorial site,

to different family members.

We’ve probably done way over a thousand in just these few days.

Hearing the names of the teachers and the children,

the names that we knew,

we still feel numb.

We’re having funerals all the way until the end of the 16th.

So even if you come next week or the following week,

we’ll still be needing help.

We probably had at least 100-plus volunteers already come in.

Most of them all call me on the phone, and they said they wanted to come help.

A lot of them were crying and they said, “Please, can we help?”

I just tell them, just make yourself at home,

go through all the cabinets

and find what you need.

And then there’s another arrangement over there too also.

I don’t even know what to say anymore because

it’s painful even talking about it.

I wake up every morning, you know, thinking about the families

that lost their children

and how they’re not going to be able to hold them anymore.

We’re going to go on because Uvalde is strong

and we care for each other in good or bad times.

We’re going to remember these children and the teachers

until we meet again.

And for months now, the community has been grappling with how much has been lost.

“As we deal with what has happened, we have a lot of questions without answers,” the Rev. Emmanuel Pacheco, the pastor of Church Time of Life in nearby Brackettville, told mourners on June 7.

“It’s OK to have questions,” he said. “And it’s OK to ask God why. God does not get offended by our questions.”

He was speaking at a viewing before the funeral for Xavier Lopez, 10. The boy lay in an open blue coffin with a Tejana hat set on top and sunflowers placed around it. X.J., as his family and friends called him, loved dancing to Tejano music and playing baseball.

The children were at an age where their families could see the people they were becoming — their talents, their personalities taking shape. Maite Rodriguez wanted to turn her passion for dolphins into a life as a marine biologist. Jacklyn Cazares — Jackie, as her family called her — talked ceaselessly about someday visiting Paris; a model of the Eiffel Tower sat on her bedroom dresser.

But families also held onto simple moments. As she spoke at his funeral, X.J.’s grandmother Amelia Sandoval reminisced about how warmly he greeted her every time she came to visit.

“We will always love you,” said Ms. Sandoval, her words overpowered by her sobs.

“I love you, baby.”

Law enforcement conducted an investigation outside of Robb Elementary School in May.

A memorial outside Robb Elementary School was filled with pictures of the victims, flowers, crosses, candles and hand-written notes.

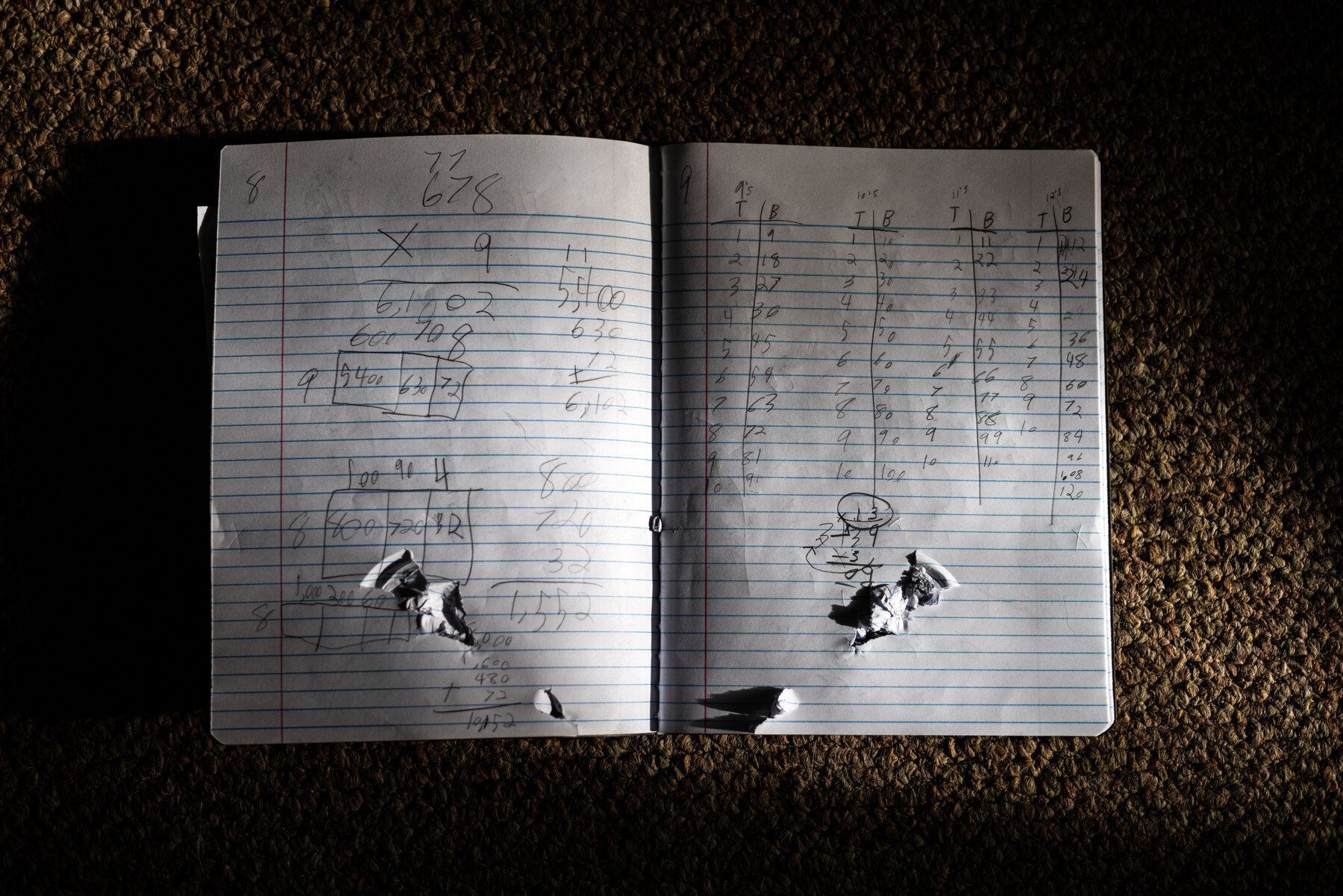

Uziyah Garcia’s math notebook was struck by a bullet during the shooting. He was among the 19 children and two teachers killed.

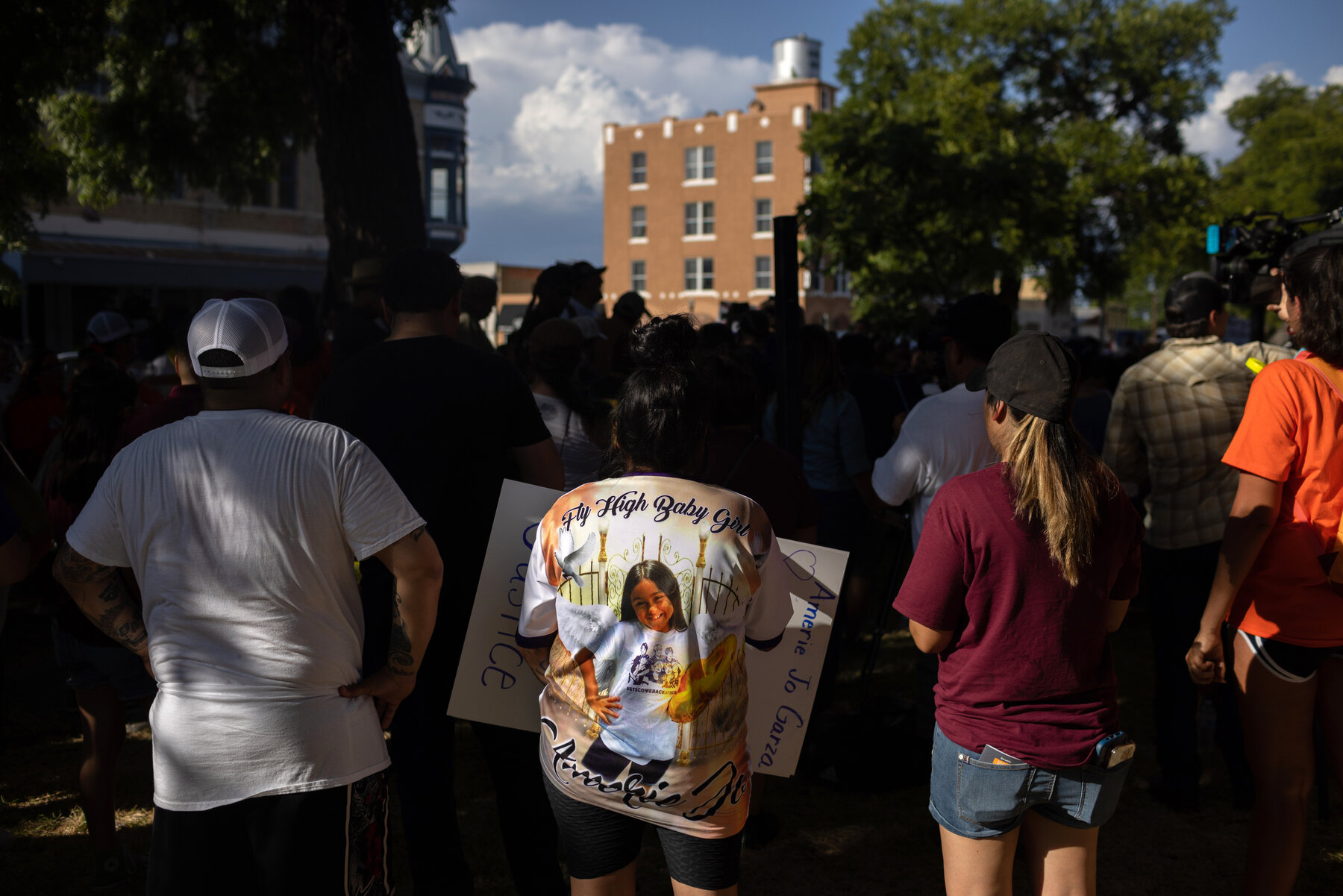

Pallbearers carried the casket of Amerie Jo Garza into Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

Donald Pinedo of San Antonio visited one of the memorials.

Funeral home employees maneuvered the vaults for the burial of Irma Garcia, who was killed during the shooting, and her husband, Joe Garcia, who died of a heart attack two days later.

Amid the tides of frustration, anger, confusion and exhaustion, all of it eddying with sorrow, the early weeks of mourning also brought moments of profound kindness.

Every day, dishes were dropped off at the Cazareses’ house — one day, chicken Alfredo; another, enchiladas — part of a meal train that was organized to feed victims’ families. “It helps,” Jazmin Cazares said. “It helps so much.”

And whatever Uvalde couldn’t handle on its own, outsiders took care of, like personalized coffins for each of the children. One man built and erected a 15-foot cross that stands on a main street. Mariachi musicians from around the region performed in the plaza at the heart of the city.

I don’t think the community in Uvalde is ever going to get over this.

Parents should never have to bury their children.

We’ve done 19 caskets in three days.

I never wanted to do children.

I wanted people who lived their life.

It’s hard to talk about, but

they still need something that represents them.

You know, we’ve got a baseball-themed casket.

The boy loved Blue Jays.

We’ve done sunflowers and glitter.

And this one little girl loved slime.

TikTok,

a lot of TikTok.

Every life and every family that we do,

I take a little piece of them with me.

I’m doing OK right now, but

when the dust settles, it will really sink in.

You know, the definition of a casket is a box for fine jewels.

And that’s exactly what’s going in these.

Huge sums of money were raised, though initially, the Cazareses decided against taking any.

“It didn’t feel right,” Gloria Cazares said. “What was it going to do? It’s not going to bring our baby back.”

Yet some in her extended family tried to persuade her to reconsider. Ms. Cazares works as a home health nurse, and Mr. Cazares has a glass installation business. The relatives asked when they expected to return to work. She didn’t have an answer.

“So, they said, OK, then you have to have a way to pay your bills,” Ms. Cazares said, recounting the conversation. “That’s what everybody wants to help with.”

The family was still reluctant, but the point had gotten through.

Javier Cazares touches a framed photo of his daughter Jackie, 9, while visiting her grave at Hillcrest Memorial Cemetery.

Mr. Cazares speaks to Jackie in her bedroom each night before he goes to sleep.

Jackie’s sister, Jazmin Cazares, 17, right, ate dinner with family members, Polly Alaniz, and Polly’s daughter Natalie, 12, at the Cazares family’s home.

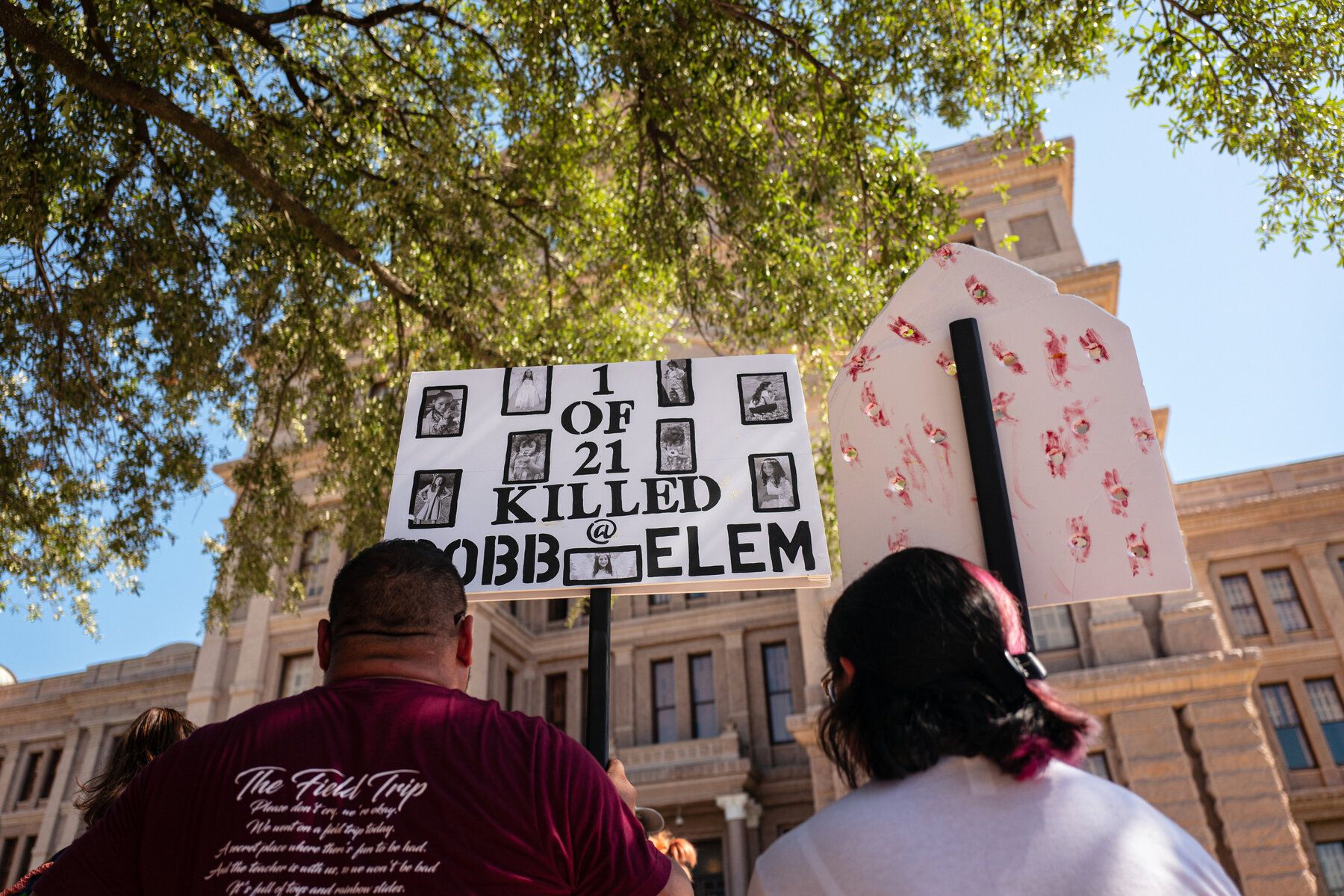

Mr. Cazares and Jazmin attended a March for Our Lives rally with their family to advocate for stricter gun control laws outside of the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

In the days after Jackie’s funeral, the Cazareses’ home bustled during the day. But at night, Jackie’s absence was inescapable.

Jazmin Cazares recently sent her sister, Jackie, a text message.

“Don’t forget to wake up early. We have summer academy tomorrow.”

Her brain had slipped into an alternate universe where, the next morning, they would be starting the fine arts program that stages a play each summer. Last year, it was “The Wizard of Oz.” (Jackie played a munchkin and a flying monkey; Jazmin did tech.) This year, it was supposed to be “Beauty and the Beast.”

Reality came crashing back.

“It was like it just hit me all over again,” Jazmin said.

A rising high school senior, Jazmin was seven years older than Jackie, but they were close. They had their sisterly squabbles, sure. “It upset me so much how she would copy me,” Jazmin said. Jazmin wanted to be a veterinarian, so Jackie wanted to be a veterinarian. Jazmin sang and acted, so Jackie started singing and acting. “I went into her closet the other day, and I saw three shirts of mine that I don’t remember giving her,” she said.

That did not mean Jackie wasn’t her own person. Her mother said she thought her nickname should be spelled Jacky, but Jackie decided otherwise. When she encountered panhandlers, she nudged her parents to give them money or buy them food.

In the days after Jackie’s funeral, the Cazareses’ home bustled during the day. Cousins came and went. Ringo, Lily, Chiquita and Roxy, the family’s dogs, demanded attention.

But at night, Jackie’s absence was inescapable.

“Everybody’s gone,” Ms. Cazares said, “and it’s just us.”

Jackie’s parents had spent their lives in the Uvalde area. Their roots were here, and they could be enveloped in the care of their sprawling families.

But the Cazareses did not dissuade their children’s curiosity about possibilities outside of Uvalde, imagining lives in places they had never visited. Jackie’s older brother enlisted in the Marines. For a while, Jackie wanted to be a Marine, too, until her brother told her about having to wake up at 5 a.m. Then, she had Paris. Jazmin dreamed of going to a university in Britain.

Uvalde High School’s prom was held 10 days before the shooting. “I went to take pictures at my girlfriend’s house,” Jazmin said, “and Jackie was crying the entire time.”

“Why are you crying?” she asked her. “There’s no reason to cry.”

“And I remember her saying that you go to prom, that means you’re going to leave me soon.”

In one of the photographs from that night, Jackie’s face was stained with tears. She was wearing a shirt she had taken from Jazmin.

Tito Moncada left an event honoring the victims of the shooting in his 1960s-era Chevrolet Impala, which has “Uvalde Strong” written on the rear window.

On June 3, the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District school board met for the first time since the shooting.

During the district all-star tournament, Marlehn Arellano, 10, held a softball during a ceremony honoring the victims.

A memorial of 21 chairs was set up outside a Head Start building.

Vic Hilderbran, a member of the Uvalde Lions Club, placed flags around the Uvalde County Courthouse in observance of Flag Day.

The memorial outside Robb Elementary School, three weeks after the shooting.

In the days and weeks after the massacre, the story of what actually happened kept shifting. The temperature kept rising.

The initial official narrative of a swift and heroic response by law enforcement quickly disintegrated. Within 48 hours, the community learned that officers had delayed — some 78 minutes — confronting the gunman.

Mass shootings have produced many activists, as families and survivors are spurred to leap into the fray over gun safety. The same was happening in Uvalde. But the police response added another dimension to the community’s anger — a fury stoked by each new fact that emerged: The police chief arriving on the scene without his radio; officers spending precious time searching for a key to open a classroom door without checking to see if it was unlocked; the police, captured on video, milling around in a hallway.

“We know he was to blame 100 percent,” Ms. Cazares said of the gunman, “but we don’t know how many kids could have been saved.”

Javier Cazares believes his daughter could have been one of them. “If she got out in time,” he said.

My name is Juan Trinidad Martinez,

and my nickname is J.T.

And I’m 9 years old, and in fourth grade.

I go to the UDLA academy.

I would have went to Robb,

but UDLA teaches both languages.

I had three cousins in that classroom.

Xavier,

Amerie

and Jayce.

Xavier was my best friend and my cousin.

He got shot right here and bled out.

He passed on the way to Hondo

because San Antonio was too far.

J.T.

I know that you’re a big man and all that.

And don’t feel like it,

but I want you to get a —

I want you to get a paper towel

Where’s my necklace?

I don’t know. Where is your necklace?

Find it.

Get a paper towel and put it in your pocket, OK?

And have your shirt.

Why?

Why?

Just in case you need it.

In case you tear up or something.

Ever since that happened,

there’s been a lot of people at our house.

I love you a lot.

I kind of don’t want it to be quiet

because there’s nothing really to do.

I’m going to miss about Xavier is,

he had a creative mind and he was very nice.

And he always showed off his dancing.

Every weekend, like every weekend, I was at their house or he was over here.

He wanted to be a soccer player,

and he loved the color red.

He was very fun to play with.

Someone who had the same interests as me.

Out of all the states in the United States,

and all the cities in Texas

and all the schools in Uvalde,

that one classroom was picked.

I mean,

I think about him more sometimes like,

like how I’m not going to see him for a long time and all that.

Public meetings grew increasingly heated as the community demanded accountability. The Cazareses participated in a rally in Austin in June calling for tighter gun laws, carrying signs and telling the crowd about Jackie.

Mr. Cazares said that he was nervous and was not sure what to say, but he felt compelled to go and speak up. “It was powerful,” he said. “I’m willing to go out there and do as much as I can.”

If the circumstances were different — if Jackie were rehearsing for her part in “Beauty and the Beast” right now — he almost certainly would not be marching for more gun restrictions.

Mr. Cazares owns an AR-15, the devastatingly powerful rifle favored by gunmen in mass shootings. Since the attack, he has resolved to have his handgun with him more. He was upset with himself for leaving it behind the day of the shooting. Maybe, just maybe, an opportunity could have presented itself, he tells himself, and he could have taken out the gunman.

But he and his wife now argue that an 18-year-old, such as the Robb Elementary gunman, should not be allowed to buy that kind of weapon.

“We’re gun owners,” Ms. Cazares said. “We don’t want to take away guns — and especially in Texas, it’s Texas. But something has to change.”

Vincent Salazar, center, the grandfather of Layla Salazar, 11, who was killed in the shooting, marched from the school to Uvalde’s town square.

Javier Cazares hugged Caitlyne Gonzales, 10, after she spoke at a rally organized by Mr. Cazares to demand accountability and policy reform in response to the shooting.

Ana Rodriguez, the mother of Maite Rodriguez, who was killed in the shooting, at the rally with family members who wore green Converse shoes with hearts drawn on the right toe. They were similar to the shoes Maite had on when she died.

In the weeks after the massacre, many family members of the victims and others in Uvalde turned to public activism.

Uvalde was now pushing into a new frontier of grief.

On July 10, a crowd assembled in front of Robb Elementary. Ms. Cazares was trying to get the protesters — the families of victims and survivors, residents, activists who had come from out of town — ready for a march. Jazmin was handing out water and taking her spot in the front.

The funerals were over. The memorial of flowers, crosses and posters that had consumed the town square had been dismantled, the plaza now conspicuously empty.

But the protest reflected the depth and intensity of the anger that remained.

One demonstrator carried a large poster with 21 coffins and the message, “This is a reminder of what you didn’t do.” Others had signs calling officers “cowards.”

“Not one more child!” the protesters chanted.

Uvalde was now pushing into a new frontier of grief, its expressions of loss now tinged with indignation and imbued with a new sense of purpose.

“This is for justice,” Jazmin told the crowd. “This is for accountability. But above everything, this is for our freaking kids.”

Produced by Leo Dominguez. Photo editing by Heather Casey.

Read the full article Here