Georgia family blames Propecia for son’s suicide

If going bald was not disheartening enough for some people, the FDA is now requiring that labels for the hair-loss pill Propecia include a warning about “suicidal ideation and behavior.”

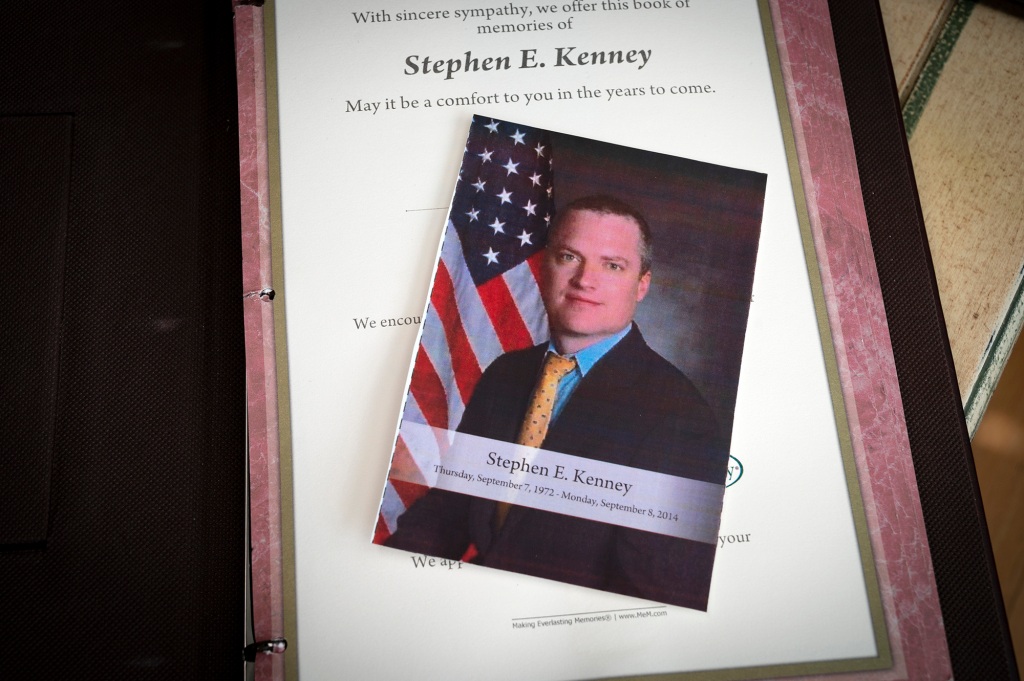

But it comes too late for the family of Stephen Kenney, a police officer from Doraville, Ga.

“We saw the changes [the drug] caused. Steve went from optimistic to morose,” Kathlene Kenney said of her son, who took his own life in 2014, at age 42. “How many people like us had to read suicide notes from their sons, saying they are sorry for putting us through this? Steve blamed himself for being vain.”

Stephen had been taking Propecia for four years; in 2013, three years after stopping, he participated in a Baylor University study about the side effects of the drug — and, according to his parents, recognized them in himself.

“There was insomnia, fatigue, sexual dysfunction and numbness in the pelvic region. Doctors doing the study at Baylor said that his problems were finasteride-related,” said his dad, Bob Kenney, referring to the generic name for the drug.

Finasteride’s original intended use was to treat an enlarged prostate by blocking the production of 5-alpha reductase, a male enzyme that also contributes to male pattern baldness. Blocking it limits the hormone DHT and reduces hair loss.

While Merck has stated that Propecia has been safely prescribed in millions of instances, some deal with brutal downsides — including depression, erectile dysfunction and a loss of sex drive, and thoughts of self-harm.

“Suicidal thoughts kicked in at around the five-month point,” one IT worker, in his 50s and living on the East Coast, told The Post. He took generic finasteride for 11 months before giving up on the dream of youthful hair. “Side effects began with erectile dysfunction, then I had brain-fog and memory loss. Suicidal thoughts followed.

“I might have done it by jumping off a bridge,” said the man, who asked that his name be withheld due to self-consciousness. “I scoped out all the big bridges in the country. The Golden Gate is nice, but I need something closer to home. It’s a bridge in my time zone.”

Almost seven years after he stopped taking it, the IT worker said, he still has a problem with ED and continues to think about killing himself.

While he’s avoided discussing his suicidal thoughts with therapists — for fear of being put on a 72-hour hold for his own safety — he did tell his son what he experienced.

!["We saw the changes [the drug] caused. Steve went from optimistic to morose," Kathlene Kenney said of her husband Rob's son.](https://mamardi.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Robert-Kathleen-Kenny-Propecia-suicide-03.jpg)

“One of my sons started losing hair in his 20s,” he said. “He wanted to have a hair transplant and the doctor told him to take finasteride beforehand. He mentioned it to me, not knowing what I’m going through, and I had to tell him everything. Can you believe how embarrassing that is? But I had to protect him — and he did not take one [pill].”

A spokesperson for Merck, the company that introduced finasteride for preventing hair loss, marketed as Propecia, told The Post, “As the innovator of Propecia, Merck continues to stand behind its safety and efficacy when used according to the label. Since the approval of Propecia by the FDA in 1997, millions of men and their doctors worldwide have determined that Propecia is an appropriate treatment.”

According to a 2020-published study conducted by Michael S. Irwig, who specializes in endocrinology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, “Men under the age of 40 who use finasteride for alopecia are at risk for suicide if they develop persistent sexual adverse effects and insomnia.” However, the study of six suicide victims added, “Further research is needed to establish whether finasteride has a causal relationship to suicide.”

The new warning came about due to petitioning from the patient advocacy group Post-Finasteride Syndrome Foundation, which tried, unsuccessfully, to have Propecia taken off the market.

In a statement to Reuters, Merck said that “the scientific evidence does not support a causal link between Propecia and suicide or suicidal ideation and these terms should not be included in the labeling” for the drug. “Merck works continuously with regulators to ensure that potential safety signals are carefully analyzed and, if appropriate, included in the label for Propecia.”

“They still market it and promote it to be safe,” Dave, a 38-year-old healthcare worker in the Seattle area, told The Post. “You think the side effects won’t happen to you and, if they do, you can quit and they will go away. But they don’t, and I am still pissed off.”

Dave said that, within a month of taking finasteride, he experienced insomnia, tinnitus, panic attacks, blurred vision and erectile dysfunction.

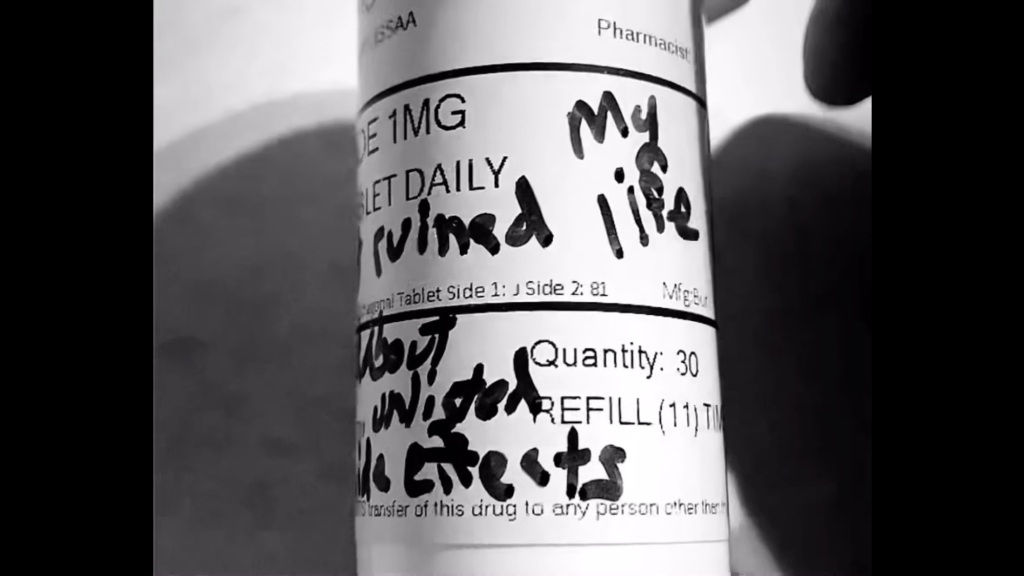

At his lowest point, he scrawled a sort of suicide note on the prescription label of his finasteride: “This s–t ruined my life. Ask for unlisted side-effects.”

He did not take the medicine long enough to experience hair growth, dropping it at the advice of doctors.

“Things spiraled when I feared my side effects might be permanent,” he said, explaining that this happened about four months after stopping. “I would lay in bed and not be able to sleep. That was when I started to feel suicidal. I engaged in self-harm. I was hitting myself in the legs and face — though I tried to avoid my face. I had to be out in public and did not want to look crazy.”

Dave estimates that he spent $15,000 on potential treatments. He recently began rounds of shockwave therapy, which uses low-intensity shockwaves to increase blood flow to the penis. Augmented with generic Cialis, Dave said, “It is countering the ED. Suicidal ideation is being resolved with relief from the sexual side effects. I remember crying in my room and thinking that if this does not work, I am dead. Shockwave therapy saved my life.”

Unfortunately, Stephen Kenney, who took Propecia from 2006 until 2010, did not have that moment of turn-around.

“Steve was a policeman and a workout addict; suddenly, during his first year of taking Propecia, he started getting vertigo and dizziness when he ran,” dad Bob told The Post.

When he also developed erectile dysfunction and depression, mom Kathlene said, “Steve feared that he would not be able to get married and not be able to have children. He started to wonder if he would be able to keep working.”

He sought treatment from physicians and psychiatrists, who prescribed medication including valium, to no avail. “He was failing physically and emotionally,” Bob said. “After a while, he had this hopeless veneer. I kept trying to break through, telling him that things would get better. But Steve, who supervised eight detectives, thought he would eventually become wheelchair-bound or end up in a hospital bed, needing to be taken care of.”

On September 8, 2014, the Kenneys received a phone call from their older son Mike, who had moved to Georgia from Chicago to take a teaching job and to help out his brother.

“That morning, Steve did not show up for a gun-training session,” remembered Bob. “Steve did not seem to be awake. So Mike went into house, entered the bathroom and saw Steve on the floor. He hanged himself from the doorknob.”

Thinking back on it, Kathlene said, “Our feeling toward the drug company is not good. It’s pathetic that a company could put out a drug like this.”

Though the suicide happened eight years ago, she added, the scars on her heart remain fresh. “We’re always thinking, what Steve would be feeling, what he would be doing, if he would have avoided this medication.”

Read the full article Here