Chris Hemsworth hypes revival of extinct, ‘iconic’ Tasmanian tiger

Why bring back the Tasmanian tiger, you ask? The better question, say scientists, is “why not?” Now, “Thor” superstar Chris Hemsworth is leading the charge to revive his unofficial native Australian mascot, The Post can report.

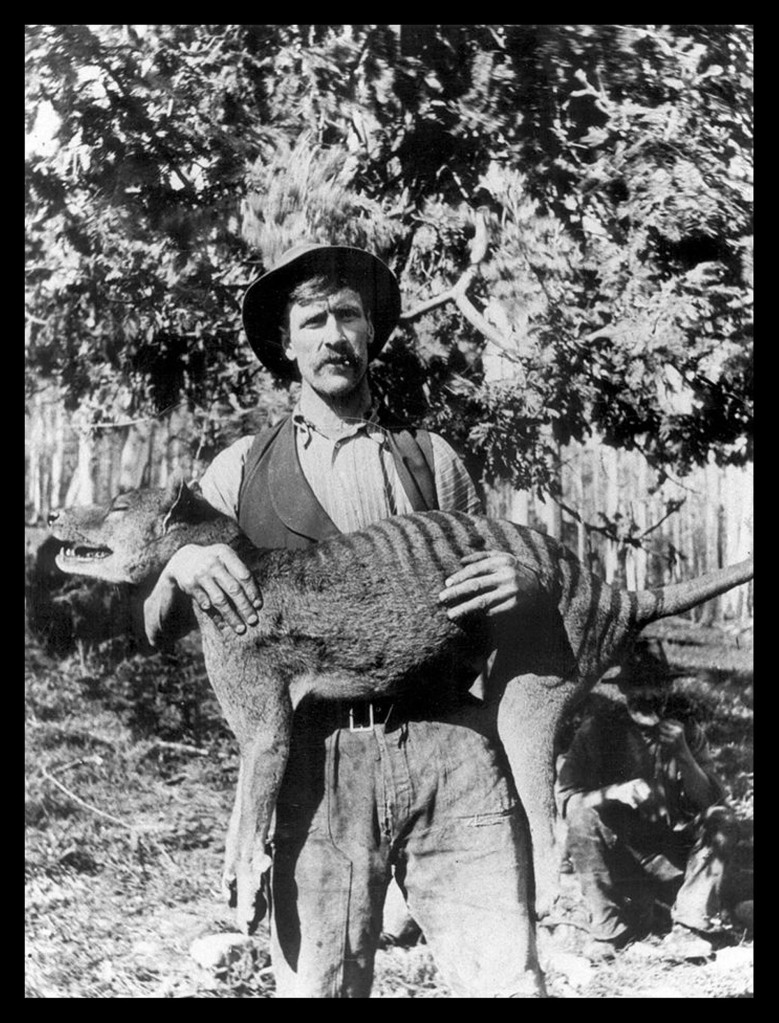

Disappeared since 1936, the marsupial known less colloquially as the thylacine resembles what one might look like if crossed with a wild dog with a tiger — and as fierce a hunter as either.

The thylacine was once a critical apex predator of the Australian and Tasmanian bushlands — regions that now lack an important link at the top of their food chain. That’s where Colossal Biosciences, a so-called “de-extinction” company, has come in. Their team of genetic engineers has a plan to re-introduce the foregone species back to its home territory, where it can once again serve to revitalize the currently unbalanced ecosystem.

And Hemsworth, for one, couldn’t be more psyched about the return of the Tassie tiger.

“The removal of an apex predator, especially due to human eradication, has a devastating effect on our ecosystem and contributes to such issues such as the spread of disease, overpopulation of certain species and the disruption of native plant life,” Hemsworth, 38, told The Post. His family, including brothers Liam and Luke, have a “long history of supporting conservationist efforts,” he explained, including those which helped reintroduce the endangered Tasmanian devil last year.

“Returning iconic species such as the Tassie tiger remain top priority,” the Marvel Cinematic Universe heartthrob added.

The star-powered announcement, with added support from noted environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio’s Re:wild organization, comes amid similar plans by Colossal to see the woolly mammoth returned to the world.

But don’t count on seeing any Tasmanian tigers, or woolly mammoths, at your local zoo anytime soon — that’s not what this is about.

“The impacts of the loss of the thylacine can already be seen with the rapid spread of new diseases like the Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease which almost led to the extinction of another marsupial species,” said Andrew Pask, Ph.D., who runs the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab the University of Melbourne. Colossal’s team enlisted Pask to lead the project.

Pask told The Post that the Tasmanian tiger’s return isn’t just a scientific stunt — and fixing a broken food chain isn’t as simple as releasing some other predator into the region.

“The Tasmanian tiger is the only marsupial apex predator that lived in modern times — so there are not any other native species that could replace it,” said Pask. “It’s very difficult to predict what a non-native predator might do to the ecosystem, which is why species introductions into new habitats can lead to ecological disasters.”

“Where a corner-stone species has been lost from that environment, the next best thing we can do is try to bring that animal back,” he added.

Of course, the act of cloning an already extinct species remains the stuff of science fiction. In this case, the Tasmanian tiger’s revival relies on supplemental genetic material from its closest living relative — which is, perhaps surprisingly, a mouse-sized carnivorous marsupial called a fat-tailed dunnart.

Living cells from the dunnart provide a map of DNA which can be tweaked to look more like that of the Tasmanian tiger. “We are essentially engineering our dunnart cell to become a Tasmanian tiger cell,” said Pask.

Ecologists have long blamed human activity — and an unfortunate case of false accusation — for the species’ vanishing.

“The thylacine extinction is a tragic story. It was an incredible animal that was not like anything else,” said Colossal co-founder and CEO Ben Lamm. Nearly a century ago, the Australian government believed the animal was slaughtering pastured sheep, so they put a bounty on the animal. “It was hunted to extinction at the hand of mankind,” Lamm told The Post.

The habitat it left behind has felt its void since. “The ecosystem it will be rewilded to is still missing an apex predator and needs this ecological niche filled,” said Lamm. “We are confident that with proper protection and no hunting bounties, the thylacine will thrive again in the wild.”

Read the full article Here