The Affidavit for the Search of Trump’s Home, Annotated

The government on Friday released a redacted version of a key document related to the F.B.I.’s search of former President Donald J. Trump’s Florida residence: the affidavit submitted by an F.B.I. agent in support of the application for the warrant.

In asking the judge, Bruce E. Reinhart of the Southern District of Florida, to approve the search, the F.B.I. had to submit an explanation of its investigation and a summary of the facts and evidence it had gathered to make the case that there was probable cause to believe a search of Mar-a-Lago would uncover evidence of a crime.

Many details, however, remain redacted in this version. While a number of news organizations, including The New York Times, had asked the judge to unseal the affidavit, the Justice Department has argued that disclosing too much of the material at this stage would jeopardize an active criminal investigation, such as by revealing witnesses.

The version released on Friday apparently reflects the redactions the department proposed. Litigation will likely continue over whether the government must reveal anything more at this stage. Below, The Times has annotated the document.

Download the original PDF.

New York Times Analysis

1

The Justice Department filed this introductory document to notify the court that it had complied with the order to file the redacted affidavit.

New York Times Analysis

2

This is the start of the affidavit an F.B.I. agent filed in support of the application for a search warrant. It is highly unusual for the government to make public any part of such a document while the criminal investigation is continuing and before any charges have been filed.

3

The F.B.I. explains the basic purpose of the investigation.

New York Times Analysis

4

The F.B.I. lays out what it had already “established” before the search. Mr. Trump was improperly keeping “national defense information” — an apparent violation of the Espionage Act. And the F.B.I. believed there was a good reason to believe that additional documents were at Mar-a-Lago that would be subject to that and two other laws cited in the application: laws against concealing official records and against concealing documents as part of an effort to obstruct an official government agency effort. The scope of what the government thinks Mr. Trump was obstructing remains unclear, but at a minimum, it would seem to be the attempt by the National Archives — later joined by the Justice Department — to do its job by taking custody of public records.

New York Times Analysis

5

A list of definitions for abbreviations and acronyms that will appear later in the affidavit foreshadows the extreme sensitivity of some of the documents the F.B.I. had already found in the 15 boxes the National Archives was able to retrieve from Mar-a-Lago earlier this year.

New York Times Analysis

6

After explaining the laws that were the basis for the search warrant, the affidavit also mentions the Presidential Records Act. That was not cited as part of the investigation, but it established that presidential records are public property. Before Congress’s post-Watergate enactment of the act, presidents were understood to own their White House records.

New York Times Analysis

7

The National Archives made a criminal referral to the Justice Department on Feb. 9, 2022, after it had finally been able to retrieve the first 15 boxes of government documents from Mar-a-Lago. The affidavit quotes the referral as indicating that the boxes contained numerous “highly classified records” that were haphazardly mixed in with other random materials rather than being properly identified and securely stored.

New York Times Analysis

8

The affidavit lays out a timeline showing how long the government had been trying to get President Trump to return the publicly owned documents he had taken with him to Mar-a-Lago. The National Archives and Records Administration made its first such request on May 6, 2021.

New York Times Analysis

9

When the F.B.I. reviewed the contents of the first 15 boxes in May, it found 184 documents marked as classified, including 25 marked as top secret. The affidavit lists abbreviations or acronyms on some of the documents indicating that they were particularly sensitive. The agent said those types of documents typically contain “national defense information,” the sort of government secret that is protected by the Espionage Act.

10

“HCS” is a reference to documents that could reveal clandestine human intelligence sources. “FISA” is a reference to national-security surveillance. “ORCON” is a reference to a special system of controls in which the person who originally marked something as classified has to be consulted before it is shared with anyone beyond those who were pre-approved for it. “NOFORN” means the information cannot be shared with foreign governments. “SI” is a reference to a system for so-called sensitive compartmented information — an extra set of limits — that is destined to protect technical and intelligence information related to surveillance of foreign communications.

New York Times Analysis

11

The discussion of early interactions with Mr. Trump’s lawyer includes the fact that he pointed out, in the abstract, that Mr. Trump had the power to declassify information when he was president. Notably, the lawyer did not then claim that Mr. Trump had, in fact, issued a standing order to declassify anything he took out of the Oval Office to his residence, as Mr. Trump’s office claimed this month. To date, no evidence has emerged suggesting that the purported order existed.

New York Times Analysis

12

The affidavit notes that classification status does not matter for purposes of the Espionage Act. That law criminalizes the unauthorized retention of closely held defense-related information that could aid a foreign adversary or harm the United States. It was enacted before the classification system existed and does not refer to classification status.

New York Times Analysis

13

The affidavit lists numerous places where agents believed Mr. Trump was haphazardly storing sensitive documents, including his residential suite.

New York Times Analysis

14

The affidavit shows that the F.B.I. had special procedures to separate any documents that might be subject to attorney-client privilege and keep them inaccessible to the main investigators. A so-called privilege review team would handle such materials before any decision about what to do with them.

New York Times Analysis

15

The unsealed materials include a May 25, 2022, letter to Jay Bratt, the head of the Justice Department’s counterespionage unit, from Evan Corcoran, a lawyer for Mr. Trump.

16

The May letter from Mr. Trump’s lawyer claims the documents were “unknowingly” packed and taken to Mar-a-Lago, implying there was no criminal intent to take government-owned documents. Many questions remain about who supervised the packing of materials Mr. Trump had taken to the residence of the White House. But in any case, the three criminal laws that are the basis of the investigation are focused not on initial theft, but rather on actions like the unauthorized retention, concealment or destruction of documents. After the National Archives’ requests for the documents — and then a Justice Department subpoena for them — Mr. Trump was clearly on notice that the government believed he had documents that did not belong to him.

New York Times Analysis

17

Mr. Trump’s lawyer put forward the abstract claim that a president can declassify anything. As previously noted, it is significant that he did not then claim that Mr. Trump had actually issued any standing order to declassify whatever he happened to take out of the Oval Office — a claim that Mr. Trump’s office made this month after the F.B.I. search.

18

Mr. Trump’s lawyer also argued that Mr. Trump is not subject to a law that criminalizes the mishandling of classified information. Notably, that is not one of the three laws that the search warrant cites, suggesting that the Justice Department did not need to rely on it and wanted to avoid a fight over whether the classification status of the documents mattered.

New York Times Analysis

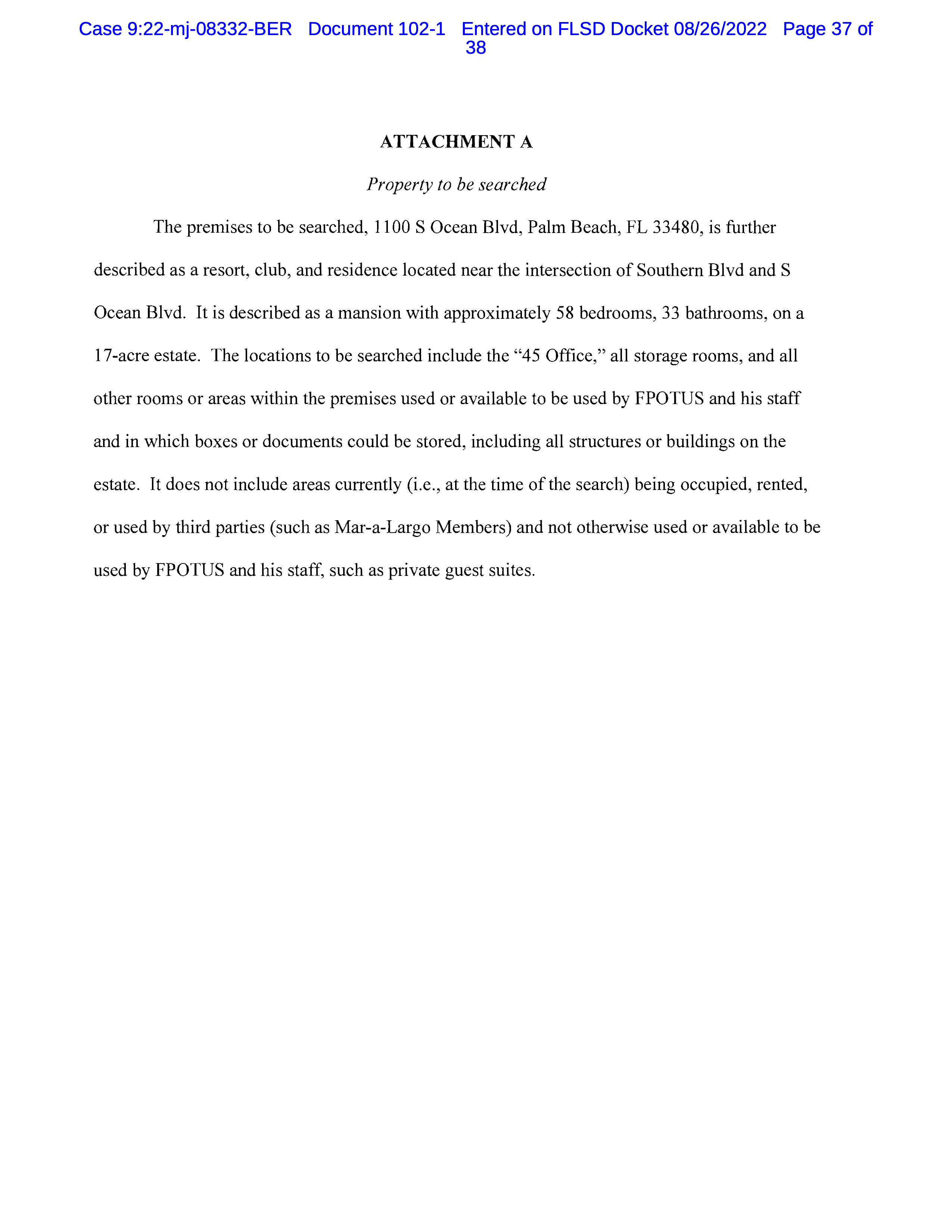

19

In this section and the next, the F.B.I. describes what parts of Mar-a-Lago it wants court authority to search and what sorts of property it wants permission to take if it is found there.

New York Times Analysis

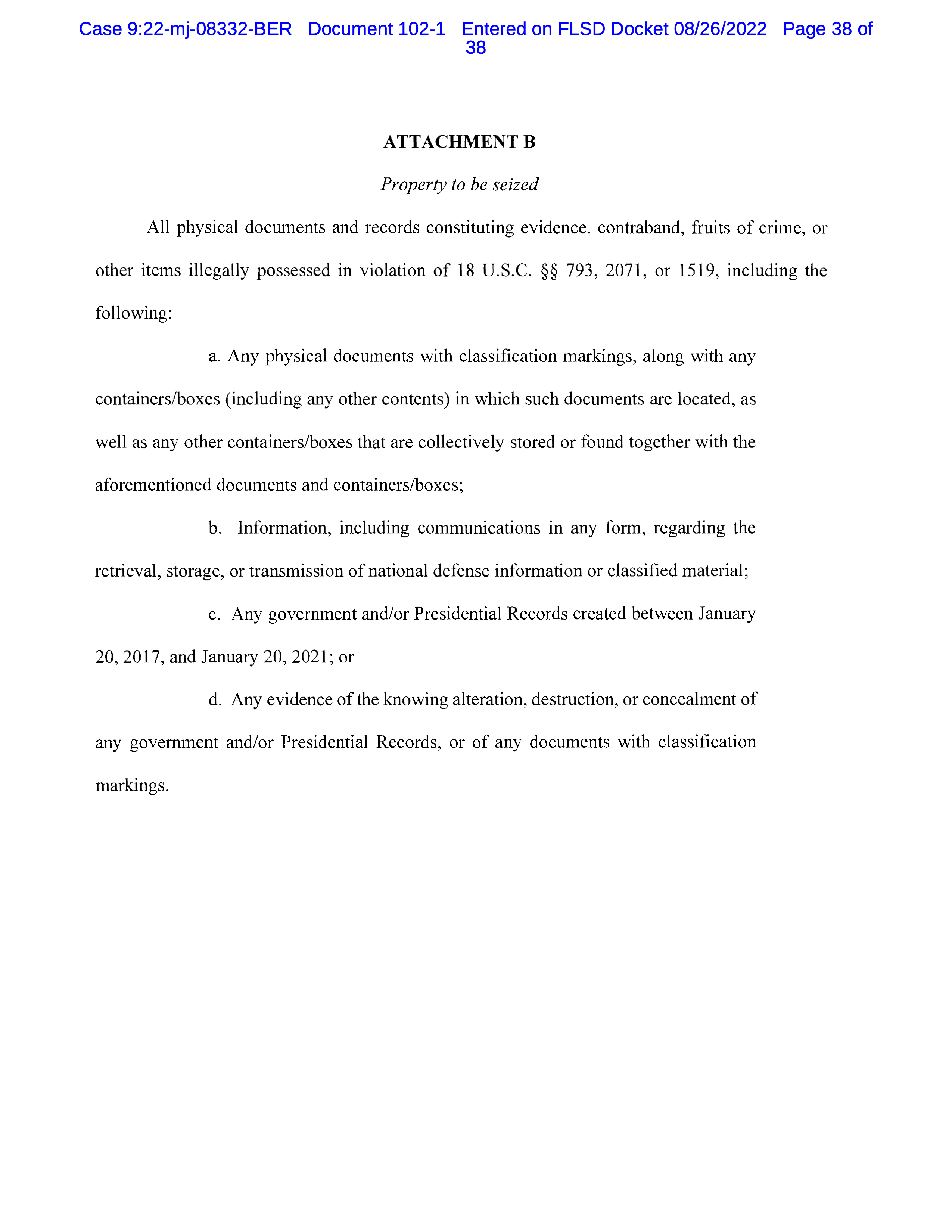

20

An attachment listing what the government wanted to seize cites the three criminal laws the investigation is pursuing. They are the Espionage Act, an obstruction law involving the concealment of documents and a law against concealing or destroying government records. Notably, the classification status of the documents is not a factor for any of those three.

New York Times Analysis

21

This document lays out the Justice Department’s arguments for keeping the rest of the affidavit censored from public view.

New York Times Analysis

22

As part of its argument for keeping agent identities redacted in the version of the affidavit that would be made public, the Justice Department’s filing points to violent threats — and worse — against the F.B.I. by some Trump supporters following the search.

New York Times Analysis

23

The Justice Department has continued to redact five categories of information from the affidavit: information that could be used to identify witnesses who might then be intimidated; information about investigative techniques that could provide a roadmap to obstructing the effort; grand jury information; the identity of law enforcement agents involved in the matter; and information that would violate other people’s privacy.

New York Times Analysis

24

The affidavit makes clear the government is working with multiple witnesses who are cooperating with the investigation.

New York Times Analysis

25

The F.B.I. says it has a “well founded” fear that Mr. Trump and his associates would seek to obstruct the investigation more if they had access to certain information that would provide a “roadmap” for doing so.

New York Times Analysis

26

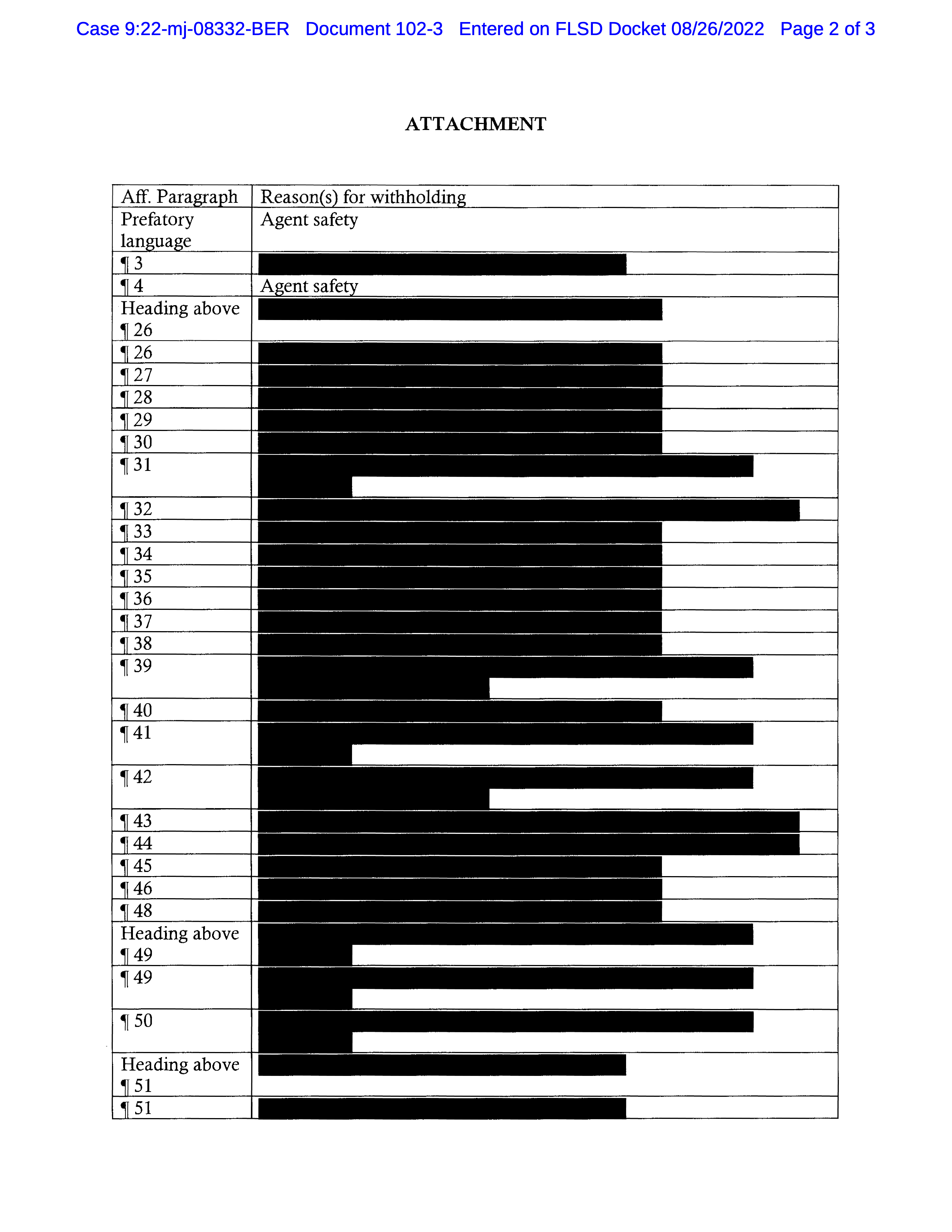

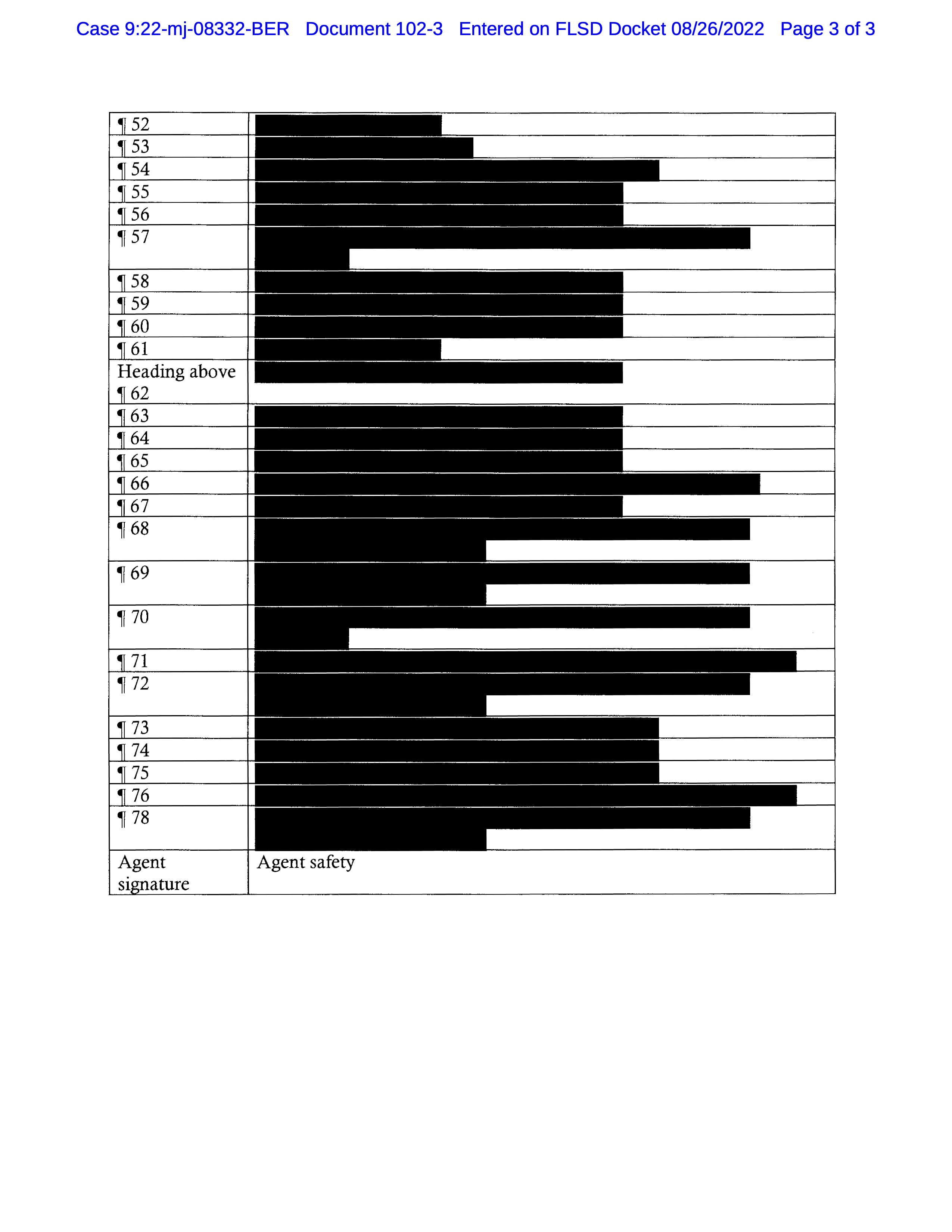

A two-page index of redactions and their justifications keeps the specific reasons censored, except for those involving the identities of F.B.I. agents.

Read the full article Here