Officer who killed suspect now teaches police, kids to get along

Jason Lehman was a cop in Southern California when he killed a suspect during a drug sting in 2009. This incident, along with past complaints about his use of force, led him to question his entire attitude to policing. In 2014, he started Why’d You Stop Me?, a nonprofit aimed at reducing fear and violent conflicts involving police. Now 41, Lehman leads empowerment seminars with police departments and community members to build trust and to show each side how to stay safe. Here, he tells his story …

They call me Tiny.

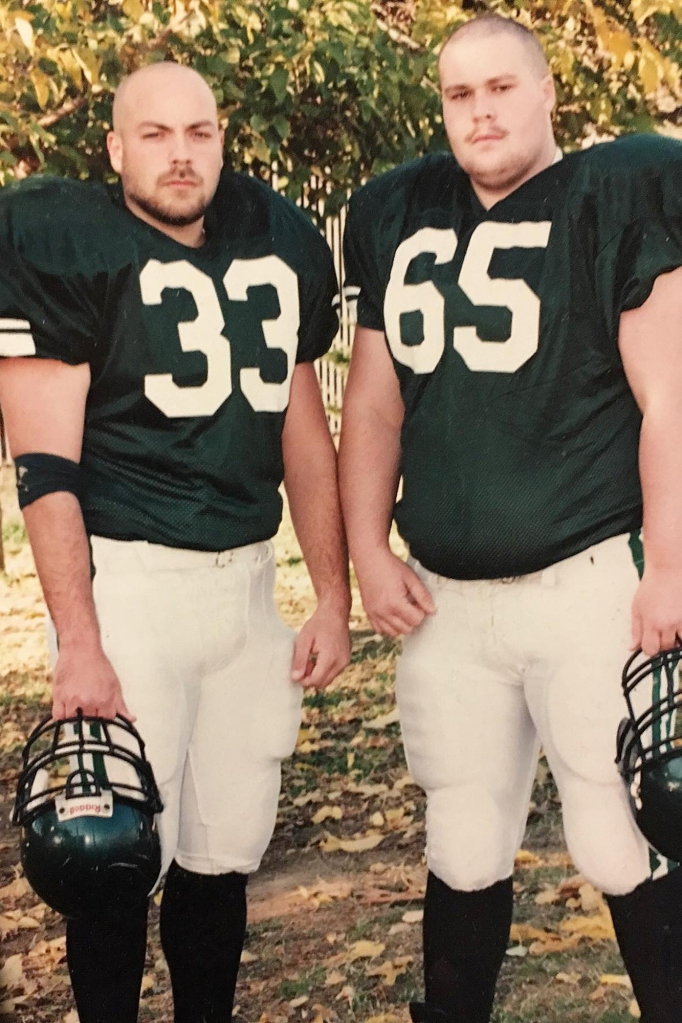

I’m 6-foot-4, 315 pounds and played football at the University of South Florida — and that’s the nickname gang members gave me in the Southern California city where I worked as a cop for more than 16 years.

It’s a community of 400,000 with a problem of violent crime, addiction and homelessness. After I joined the police department in 2006, I served on a street crime unit doing gang suppression. We did numerous high-risk search warrants and made a lot of arrests.

My job was to force open people’s doors with a battering ram to serve these warrants. I saw myself as the enforcer. When someone looked at me sideways, it was on.

In those days, I made decisions that broke down the trust between police and the people I was sworn to protect. At times I used profane language, slapped on cuffs too tightly and ignored simple requests related to the needs of people I’d arrested. They were forms of disrespect back then that were tolerated by some of the officers I worked with. It was often us against them.

In my early years, I had more than a few internal-affairs complaints related to misconduct allegations. One was for excessive force, and in 2009 I got suspended. My boss told me, “I don’t think you deserve to be a police officer. You need to control your inner idiot. If you don’t, you’re not just going to get fired. You’re going to go to prison.”

Then, in 2009, during an undercover operation, my partner and I chased a suspected drug dealer down the street. He was a local gang member, and we’d heard from our informant that he had a gun in his waistband.

He went into a building, up a staircase and jumped from the second floor to the sidewalk. He punched my partner, and I tackled him. My partner had his gun out and the suspect was reaching for my partner’s arm, and I also thought he had his own gun, so I hit him with my sap. It’s a short, flat metal baton wrapped in leather that was commonly used in law enforcement back then.

His body stopped moving and I watched him stop breathing. We called for medics and the Fire Department brought him back to life. But he went into a coma and ultimately he died.

The District Attorney’s Office looked at me as a homicide suspect — or so it felt to me. I was separated from my peers. I had to see a psychologist. They cleared me of any wrongdoing, and I was allowed to go back to work.

But I had one question: could I have done something differently or better?

The use of force was said to be OK — and I believe I would still handle it the same way — but I also knew from my past there were dozens of times when I could have done better. And I was trying to get these wrongdoings out of my head.

For about a year, on dozens of occasions, I would go home, sit on my couch and plot and plan how to kill myself.

I found therapy, and having a safe place to tell my story saved my life.

Even before that incident, I had started making changes to do things right. It made me realize the bad I had done. Those decisions, which nearly wrecked my career and ended my life, also made me wonder. What would it look like if police and community members could better understand each other’s perspectives and trust each other more?

“Those decisions, which nearly wrecked my career and ended my life, also made me wonder. What would it look like if police and community members could better understand each other’s perspectives and trust each other more?”

Jason Lehman, reflecting on his mistakes as an officer and how he vowed to help others do better

In April of 2011, we heard that a violent local street gang was planning to ambush us in this park — retaliation for the guy whose life I had taken. My department, being concerned for my safety, took me off the streets. And it just so happened that at that time I had a friend, a teammate from junior college who was an assistant principal, who invited me to speak to his classroom of at-risk youths.

I felt like it was God intervening.

I started telling them about what I do and why. Why it’s scary to be a policeman. Every aspect was my fear. This kid in the back stood up.

“Hey, Tiny,” he says. “Remember me? You arrested me two years ago.”

He was right. I had arrested him right across from the school. He was 15 then and had a gun in his waistband.

“Before today, I had plans to hurt you,” he said. “But this is the first day I recognized you. It’s the first day I can say that I respect a cop.”

This kid talked for about a minute. He took over the room.

“It was raining that day, and yeah, I was carrying a gun. I was wearing new clothes my mom had just bought me with the last money she had because I was on my first date. My girl and I were holding hands, and you made me get on the wet concrete and crawl to you.

“My mom was across the street watching from the window. She came down after I was arrested and was crying. But another officer refused to answer her questions. Wouldn’t your mom want to know more?

“I was carrying a gun because my brother had just been shot in front of our apartment complex. I was now the man of the house and had to protect my family. If that had happened to you, wouldn’t you be carrying a gun, Tiny?

He said: “Your safety matters, but why don’t you start thinking for us, too?”

I was blown away. I felt almost paralyzed by what this young man had to say. I began to realize how important it was to think for the other side.

I walked out of that classroom and my friend asked me, “What’s the name of your program?” I didn’t have one. He said, “You can’t stop doing this. You just gave these kids what they need to survive their next police encounter.”

I left with a greater sense of connection to men and women of color. I asked myself, “Why aren’t we empowering these young people to get along with authority figures?” We also needed to change the way that cops are trained to communicate.

I knew I had a mission.

But I didn’t have a name for what I wanted to create. These kids always wanted to know why I’d stopped them. So that’s how I came up with my nonprofit name, “Why’d You Stop Me?”

We started training in 2012 and established our nonprofit two years later — with the mission to educate both sides to reduce violent confrontations. Our team has many amazing members, including current and retired law-enforcement officers, two pastors, and an inspiring counselor who overcame drug addiction after being kidnapped by a gang and sexually assaulted.

Most of us have come through tumultuous situations, but our stories provide legitimacy to the people we’re educating.

Our program connects members of the community and the police. It’s about learning more from each other. We ask young people to play the role of a police officer making an arrest. We tackle issues involving race. We challenge people to see opportunities to build trust and respect.

It’s not just about getting through a stop safely. It’s about reducing fear on both sides. Because you can’t have violence without fear.

Some cops and community members don’t recognize how cynical they can be — and how that can affect their behavior. Law enforcement has a paramilitary culture. But that shouldn’t stop officers from finding ways to build trust, as long as doing so doesn’t jeopardize their safety.

There has to be proactive engagement, which can involve as small a gesture as waving to a community member at a stoplight and offering a genuine smile. “Hey, I’m Jason. I work in this neighborhood. I’m out here with you.”

In proactive policing, there are times when violence is necessary, but cops also must be mindful of the value of treating suspects with dignity.

We watch videos showing examples of use of force, and our participants are challenged with real-life scenarios in the classroom. How could this situation have been handled differently? Are you allowing others to have a voice?

We encourage officers and community members to change the words they use. If a suspect is struggling, many cops will say, “Stop resisting!” But what does that mean to a suspect if he or she has never heard that before? A mother doesn’t tell her child, “Stop resisting!”

“Humanizing the badge makes everyone safer.”

Jason Lehman on how his work with the police and communities is helping reduce violence

So if they are punching or kicking, wouldn’t it be better to say, “Stop punching me! Stop kicking me!”

Or an officer might order a suspect to “comply” or “relax.” Those words rarely do anything to de-escalate a dangerous situation.

To date, our organization has trained about 45,000 youths and adult community members in 22 cities and five states. And our program, “TAG: Together Achieving Greatness,” has gone everywhere from seventh-grade classrooms to jails and prisons.

We’ve also worked with more than 10,000 police officers. There are 70,000 in the state of California. My goal is to train every one of them.

And I don’t want to stop there. Why not New York? Why not the rest of the country?

In 2014, the city of Salinas, Calif., an agricultural community, largely Hispanic, had one of the highest use-of-force rates in the state. Over the next two years, we trained thousands of community members and cops there. And we saw a huge reduction in violent encounters.

Two years ago this week I was sickened by what happened in Minneapolis when Derek Chauvin kept his knee on George Floyd’s neck as he begged for his life and was killed. His murder filled me with anger and frustration — and serves as a reminder that the work we are doing is more important than ever.

Last year, there were 1,055 fatal police shootings, and 625 cops died in the line of duty. And the numbers are going up. These acts of violence must stop. What we’ve been doing clearly isn’t working.

The key to solving the problem is encouraging people to find common ground. Many of the participants in our programs have talked about the value of holding themselves accountable for their actions.

Each of us needs to ask, “What can I do to help?”

Because humanizing the badge makes everyone safer.

— As told to Brad Hamilton

Read the full article Here