British opera fans saved Jewish refugees from Hitler’s camps

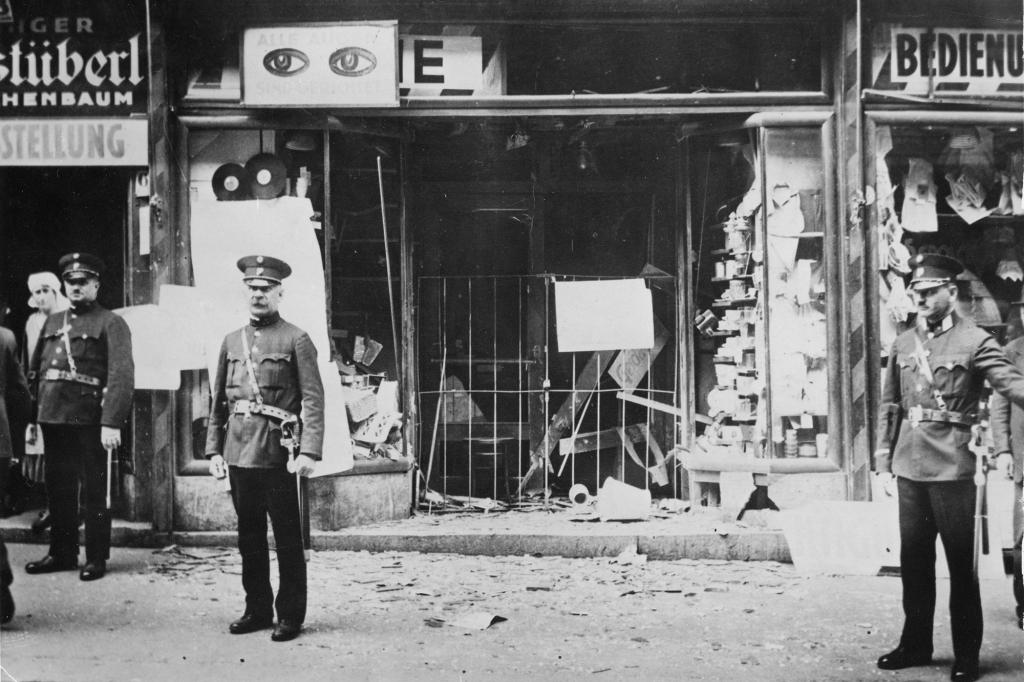

The small dinner party was assembled in haste at the partly destroyed gothic mansion on Frankfurter Strasse in the week after Kristallnacht.

On November 10, 1938, the second night of the state-sanctioned pogroms that ripped through Germany and Austria, a marauding group of Nazis had stormed the Offenbach residence of German-Jewish industrialist Oswald Basch. Fifteen Nazis had “forced their entry into the house and smashed most everything,” recalled Basch’s youngest daughter, Lisa, an aspiring medical student who had to give up her studies when the Nazis came to power.

They had ripped out cabinets and thrown them down the grand staircase and shattered a Venetian mirror. They hammered beyond recognition a Dutch painting that once had pride of place in the oak-paneled library where the family often held musical evenings. The grand piano was also destroyed. The intruders had torn out all of the ivory keys.

One guest at that fateful dinner party recalled that they stood ankle-deep in broken glass as their hostess apologetically offered them drinks: “The daughter appeared with a tray containing one liquor glass, one champagne glass, one egg-cup and one water glass. This was all the drinking vessels left in the super-wealthy cultured and well-ordered household.”

For the Basch family, the dinner was of utmost importance — their chance to meet Ida Cook, a 34-year-old English woman who they hoped would be their savior. Ida, a gawky former clerk in the London law courts and budding romance novelist, had traveled to Germany to plead with the British consul in Frankfurt to help another Jewish family. Irma and Ilse Bauer, a Viennese mother and daughter, were trying to escape to the United Kingdom on domestic work visas — one of the only ways they could seek refuge in Britain after countries around the world shut their borders to Jewish refugees.

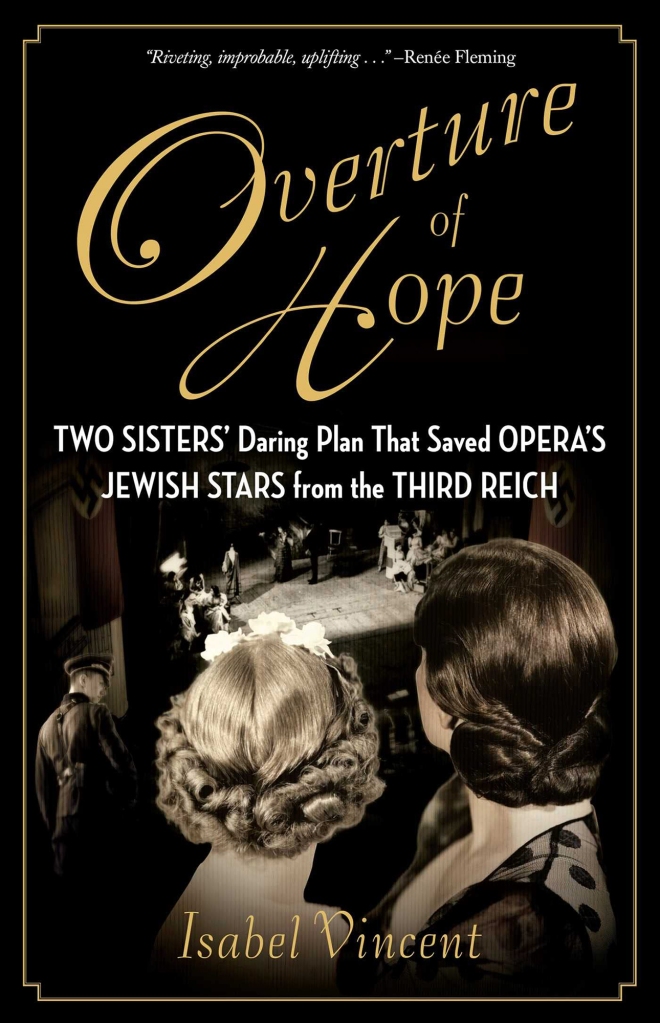

Ida and her older sister Louise had developed a following among the Jewish underground in the Third Reich, and their exploits as well as the stories of the 29 families they saved are chronicled in my book, “Overture of Hope: Two Sisters’ Daring Plan that Saved Opera’s Jewish Stars from the Third Reich” (Regnery History), out now.

The sisters were opera groupies who had befriended some of the biggest divas of the 1920s and 1930s. Among the luminaries was Austrian conductor Clemens Krauss and his wife, the Romanian soprano Viorica Ursuleac. Krauss, a music world opportunist, became a favorite of opera-loving Adolf Hitler, who appointed him to head up the Munich State Opera, the most important cultural institution in the Third Reich. Despite his zeal to take over plum appointments left vacant by conductors who refused to perform for the Nazis, the imperious conductor was also desperate to save the Jewish musicians and scholars he worked with in Austria and Germany. In the mid 1930s, he saw an opportunity in his two adoring British fans.

In the years before the beginning of the Second World War in 1939, the Cooks spent their weekends attending Krauss’ opera performances, which were really a ruse for them to interview potential refugees, and smuggle out their valuables.

“We built ourselves a reputation,” Louise Cook told two US reporters after the war. “The men in customs used to chuckle, ‘Here come those two verruckt (crazy) English ladies. They are only poor office workers and they spend their money to come here to listen to German opera.’”

When they returned to London after a weekend at the opera in Munich, Vienna, or Berlin, they did so laden with the glittering jewels, Swiss watches and furs belonging to refugees who would otherwise have had to surrender their valuables to the Nazis upon their exit from the Reich. They wore gold pendants and plastered diamond brooches on their Marks & Spencer dresses, gambling that the expensive jewelry would surely look fake. They hammed up their roles as “a couple of nervous British spinsters” but their plain, practical exteriors hid romantic souls — real-life heroines in the 20th century’s darkest opera.

In England, they established a small network of friends and strangers who came forward with offers of financial guarantees for the refugees. Others contributed in smaller ways. One friend walked halfway to her office everyday and gave the Cooks the saved bus fares to buy the postage necessary for their work. Another friend cut her cigarette consumption in half and contributed the money toward one of their cases.

As thousands of Jews tried to leave Austria and Germany in the years after the Nazis took power in 1933, the Cooks had become so famous that letters often arrived at British consulates addressed simply to “Ida and Louise.”

“The men in customs used to chuckle, ’Here come these two verruckt (crazy) English ladies.’ ”

Louise Cook, as told in a new history

Lisa Basch and her mother, Helene, put their last hopes in the Cooks. Oswald, his head freshly shaved, had recently been released from the Dachau concentration camp after a British business acquaintance was able to guarantee a visa for him in the United Kingdom. His two sons had already emigrated to the US, and a married daughter was in the process of leaving the country. But Lisa, then 26, and her mother were stuck in Germany with no prospects.

Ida decided to help the family even before they sat down to dinner at the Offenbach home. Although Lisa and her mother had managed to obtain US visas, their “quota” number would not come through for a few years, and following the reign of terror against Jews after Kristallnacht, they needed a temporary sanctuary to await their turn to enter America.

“Though she had never met us before [Ida] invited my parents and me to her apartment in Dolphin Square, London, to await our American quota,” wrote Lisa Basch in a letter to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. In 1965, the Holocaust memorial made the sisters “Righteous Among the Nations,” among the first women to be honored by Israel for their work saving Jews.

“For myself Miss Cook had approached a Member of Parliament to guarantee my years in England as she herself had guaranteed for too many already,” wrote Lisa, who left Germany in April 1939 and traveled to London via Paris where she stayed in the Cooks’ one-bedroom flat, which was crowded with 14 other Jewish refugees as the war began in the fall of 1939.

“My family felt that Ida and Louise were real giants,” said Loren Basch, Lisa Basch’s nephew, now 78. “They never ceased what they thought they had to do to help someone.”

The Cooks’ help did not stop with getting Lisa and her mother out of Germany. Through their New York opera connections, the Cooks helped Lisa find an apartment on West 153rd Street. Lisa worked at Columbia University in the photography department and lived in the one-bedroom flat until her death at 94 in 2006, according to public records.

Lisa and her family remained lifelong friends of the Cook sisters, attending opera with them at Lincoln Center whenever they traveled to New York. Lisa was often dispatched to drive them around the city, said Loren.

“Lisa was bitter, and she was angry,” said Loren Basch, from his home in Tulsa, Okla. “Her life had been shattered and she really never got over it. She never spoke German again and she wanted nothing to do with Germany after the war. She felt very much like her life had been taken away from her. She started over on her wits.”

In addition to her harrowing escape from Germany, Lisa had lost the love of her life — a rabbi who had been shot by the Nazis in France, said Loren.

In contrast, her older brother Frederick flourished once he left Germany. He became one of the first German refugees to volunteer for the US Army to fight in the war. He returned to Germany after the US declared war on the Axis powers, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

“He showed up at the recruiting officer, and in a heavy German accent said, ‘I want to drive a tank through Berlin,’’ Loren told The Post. “My dad had a real spit-in-your-eye attitude about Germany.”

According to his son, Frederick drove a series of Jeeps through Germany, working as a translator for US military brass and helping the Monuments Men, a group of soldiers who gathered up art that was stolen by the Nazis in occupied European countries at the end of the war. Frederick even managed to save his father’s desk, which sits in the family home in Tulsa, he said.

Later, Frederick worked as a military research assistant on the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, a 1947 report that analyzed the effects of Allied bombing raids on Nazi Germany. Frederick later moved to Los Angeles, where Loren was born. The family went on to Salt Lake City where Frederick, who worked in the aerospace industry after the war, was transferred. For his part, Loren worked as an executive in the Jewish community for more than 30 years, he said.

As for Lisa, she roamed the streets of New York after she retired from her job at Columbia University, said Loren.

“She went out on expeditions everyday,” said Loren, who accompanied his aunt on his frequent trips to New York when he was a teenager. “She carried herself like an aristocrat, but she walked around New York City like a kind of bag lady in her final 25 years.”

“She was very much a victimized Jew, who could never forget the war,” he said. “But she never forgot what Ida and Louise had done for her and our whole family.”

Read the full article Here