After Uvalde, a Cemetery Anchors Families of Victims

Alexandria Rubio’s mother and sister approached her grave one morning, the dark ink still fresh on their skin.

“My Lexi-roo, we got a tattoo for you!” Kalisa Barboza, 18, shouted, facing the headstone. They were visiting the cemetery, as the family has done nearly every day in the year since their 10-year-old daughter, known as Lexi, was killed along with 18 other students and two teachers at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas.

Ms. Barboza and her mother, Kimberly Rubio, raised their upper arms. “Destination Lexi,” the matching tattoos said in elegant cursive, a reminder of the women’s belief that their family will eventually be reunited.

NOVEMBER Siblings and a cousin of Rojelio Torres, who was killed in the shooting, in the cemetery on Thanksgiving.

The families of the 21 people who were killed have spent the last year working their way through a wilderness of grief, anger, despair, frustration and confusion — searching, if not for peace, then at least purpose.

The cemetery, where most of the victims are buried, has become an anchor for many of the families, as has the bond forged among them. The families decorate the graves and meticulously maintain the area surrounding the headstones; and together, they gather at the cemetery to celebrate birthdays and holidays.

APRIL Felix Rubio, Lexi’s father, at her gravesite. “I’m always thinking of her every month,” he said, “every week, every day, every hour, every minute, every second.”

Mass shootings have continued to occur across the country since the Uvalde massacre, and the process of recovery in the months since has been slow, moving season by season.

“Time doesn’t heal,” said Ana Rodriguez, whose daughter Maite was among the dead. “It shows us how to learn to live with the pain.”

In the wake of the tragedy, most of the families were drawn to the cemetery. In early June, mounds of dirt rose above the fresh graves of nearly a dozen 9-and-10 year-olds in the northern section, a constellation of anguish. Half of the victims were buried there. The others occupied places beside relatives elsewhere in the cemetery. A few were cremated.

AUGUST Gloria and Javier Cazares watch a school board meeting in their daughter Jacklyn Cazares’s room.

AUGUST Ana Rodriguez wipes her eyes while reading a letter she wrote to her daughter, Maite.

In Uvalde, the small, mainly blue-collar and mainly Latino town not far from San Antonio, people run into each other at school activities and the town’s only supermarket. Now, these families are also connected through grief and, for many, a new sense of purpose: They want accountability for the well documented law enforcement failures of May 24, 2022, and changes in law that they hope will prevent other families from experiencing the same fate.

JUNE Mr. Cazares at his daughter Jacklyn’s grave two days after what would have been her 10th birthday. Her family left flowers and rocks painted to resemble ramen noodles, the Eiffel Tower and things she loved.

JUNE The Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District school board meets for the first time since the shooting.

AUGUST Relatives of the shooting victims stand before dawn outside the Texas Governor’s Mansion in Austin, repeating the names of their loved ones. “We lost a child,” Ms. Cazares said. “We lost all her friends. Our friends lost children. It’s so much.”

They packed school board and city meetings and held rallies, many relatives calling for stricter gun laws. Like the cemetery, the halls of power in Austin and Washington D.C. became familiar places.

“I feel like her chapter closed and mine opened,” Ms. Rubio said of her daughter. “I feel this responsibility to her to share her story and to make change for her.”

SEPTEMBER Relatives of victims gather at the memorial in the plaza before the first day of school. “These people that I’m holding hands with, they feel exactly the way I feel,” Ms. Rodriguez said.

SEPTEMBER Ms. Rubio with her son Julian Rubio, 9, the morning he was to start third grade.

SEPTEMBER A Uvalde school bus on the first day of school.

Early on, the families began supporting one another and managing the logistics of their interwoven lives using a private message group they called “21 Angels.”

The evening before the first day of school in September, some of the parents expressed their anxiety and dread to the group. “Anyone up for a quick visit to the plaza?” Gloria Cazares, whose daughter Jacklyn, known as Jackie, was killed, wrote in response.

A little over an hour later, nine sets of parents formed a circle near the crosses still standing in the town plaza. They held hands and prayed.

By November, the swollen dirt above the graves had settled, and lush grass was starting to take hold. Nearly all the families gathered at the cemetery to observe Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, a traditional Mexican holiday when people commune with loved ones who have died. They set up ofrendas, and took turns visiting altars for the children and teachers.

OCTOBER Ms. Rubio and her husband, Felix, shop for decorations to celebrate what would have been Lexi’s 11th birthday.

OCTOBER Ms. Rodriguez gets a tattoo of her daughter’s name.

OCTOBER Lexi’s family beside her grave on what would have been her 11th birthday.

“I like to think that we’re not bonded by just the tragedy, but by shared memories of our children,” Ms. Rubio said. “It’s almost like this puzzle that none of us have access to unless we’re together.”

OCTOBER Ms. Cazares whispers to Ms. Rubio, during an event to remember their children and the teachers who were killed in Uvalde.

NOVEMBER Uvalde families carry a Day of the Dead altar honoring the 21 victims from the Texas State Capitol to the Governor’s Mansion in Austin.

The day before, a group from Uvalde traveled to Austin, where they carried a Day of the Dead altar from the State Capitol to the Governor’s Mansion nearby. They were demonstrating in favor of tighter gun regulations, including raising the minimum age to buy an assault rifle to 21 from 18. The gunman, who was 18, legally purchased the assault rifle used in the shooting.

NOVEMBER Ms. Cazares and her family sit by Jackie’s grave after the Day of the Dead gathering.“I don’t want the world to forget her,” Ms. Cazares said.

NOVEMBER Parents of the victims vow to continue fighting for stricter gun laws after Beto O’Rourke, who backed their pleas, lost the governor’s race. “We’re not done!” they chanted.

Back home, the pain of experiencing the first of many cycles of milestones without their lost family members was unrelenting.

SEPTEMBER Veronica Mata, Tess’s mother, and other relatives of Uvalde victims, ride a bus to Edinburg, Texas, to support Beto O’Rouke’s candidacy for governor.

SEPTEMBER Uvalde families meet with members of Texas Senator John Cornyn’s staff in Washington. “It’s moms and dads trying to prevent other moms and dads from being in our shoes,” Ms. Cazares said.

SEPTEMBER Brett Cross, uncle and guardian of Uziyah Garcia, along with other relatives and supporters, camped out in protest against the school district’s handling of the school police officers who were slow to respond to the shooting.

At 6 a.m. on the day before Thanksgiving, Ms. Cazares and her husband, Javier, were the first to arrive at a Uvalde banquet hall for “Luv Ya Uvalde,” a Thanksgiving lunch that the family holds annually for the community. In the dim light, surrounded by empty tables, the couple held each other, wiping away tears. Each member of the family had a role in organizing the lunch and serving food during the event, which was a favorite of Jackie’s.

NOVEMBER Jackie’s family prepares food for the annual “Luv Ya Uvalde” event, which they took over hosting before Jackie was born.

NOVEMBER Gladys Gonzales, center, hugs Polly Flores, Jackie’s aunt, during “Luv Ya Uvalde.”

NOVEMBER Evadulia Orta, whose son Rojelio was killed, consoles her son, Federico, while her daughter Sara arranges a wreath on Rojelio’s grave on Thanksgiving.

“We’re now realizing she was not just a little part of our family,” Ms. Cazares said. “She was probably the biggest part of our family.”

Ms. Cazares got to work to distract herself. Then her older sister approached her and asked, “Who’s in charge of dessert?”

Ms. Cazares paused. “Jackie was.”

Xavier Lopez, known as X.J., loved the holiday season. In late November, his family attended his favorite event, Uvalde’s annual Christmas extravaganza.

DECEMBER Steven Garcia, father of Eliahna Garcia, poses for a Christmas photo.

As his parents, Abel Lopez and Felicha Martinez, and his siblings walked through the elaborate trail of lights and decorations to a soundtrack of a children’s choir, a loud blast pierced the air. An overloaded transformer had burst, cutting the power briefly. Ms. Martinez had a panic attack and collapsed on the grass.

NOVEMBER Mr. Lopez and a relative comfort Ms. Martinez during a panic attack while their granddaughter Katalina Mata, 2, looks on.

DECEMBER Uvalde families march in Washington to support a proposed assault weapons ban. “I can travel to D.C. and fight, but I can’t make chicken alfredo,” Lexi’s favorite dish, Ms. Rubio said. “You’d be surprised what you can and can’t do.”

DECEMBER Mr. Cazares at an annual vigil for victims of gun violence in Washington.“I wish I could be stronger for our family,” he said.

“These days are supposed to be happy,” she said later that evening, “but they are just reminders that our lives are torn apart.”

JANUARY Faith Mata looks at a flock of passing birds while decorating her sister Tess’s grave.

JANUARY Mr. and Ms. Rubio shop for Valentine’s Day decorations for Lexi’s grave and her cross at the plaza.

JANUARY Kandace Morales and Arabella Torres, relatives of Eliahna Torres, visit a room in Eliahna’s family’s new home that has been decorated in her memory, on what would have been her 11th birthday.

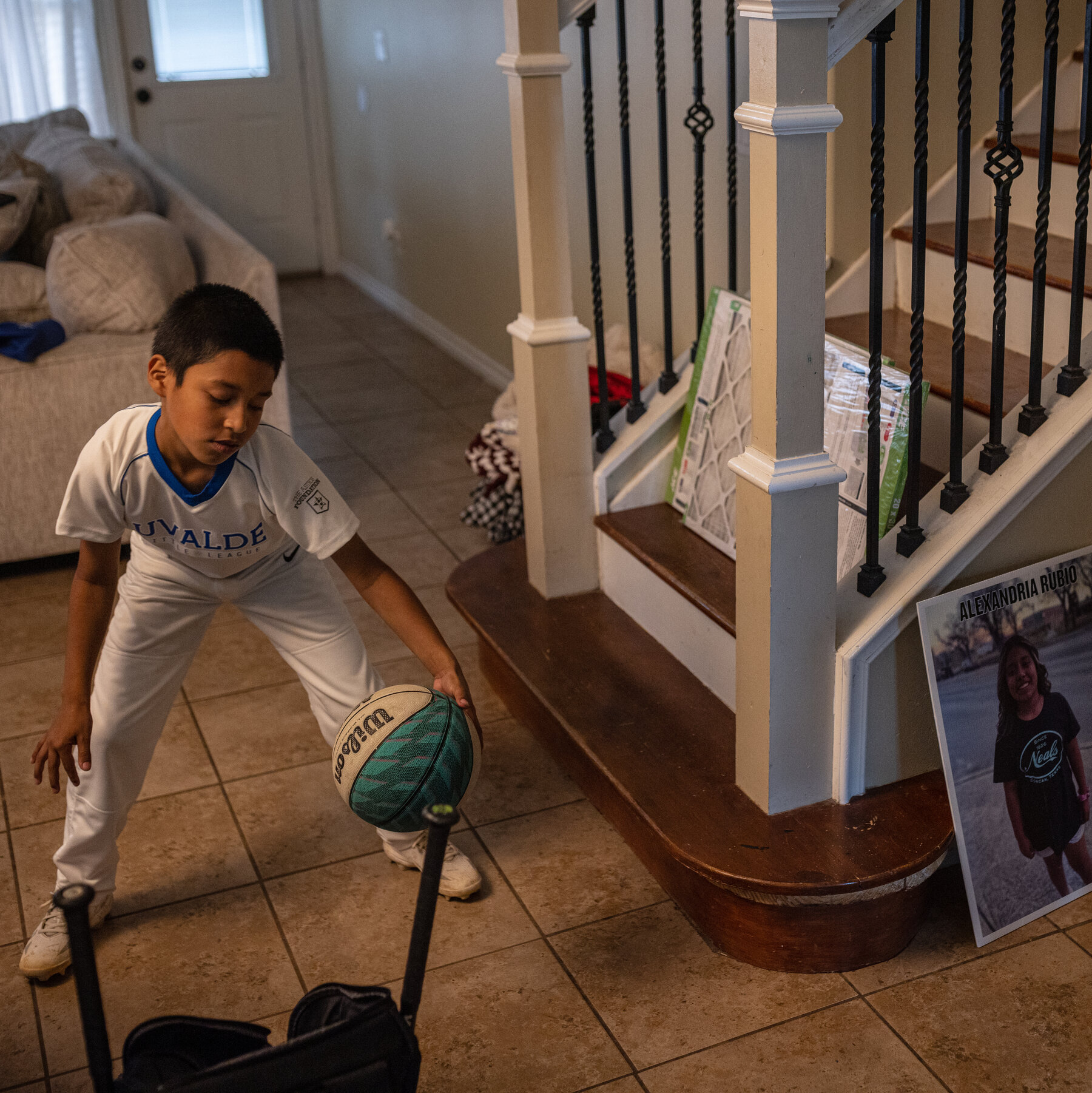

MARCH Julian, Lexi’s younger brother, at home before a baseball game.

Other reminders are more subtle.

Before her death, Tess Mata made a lot of noise at home. When the 10-year-old wasn’t singing along with TikTok videos or talking to her older sister on the phone, she was roller skating around the living room, the pink wheels making a distinct click clack over the tiled floor.

“When Tess was quiet, you worried,” said Veronica Mata, her mother.

MARCH Mr. and Ms. Rubio hang photos and artwork of Lexi at home. Lexi loved math, wanted to be a lawyer, and was a basketball and softball player with “a cannon for an arm,” Mr. Rubio said.

DECEMBER Ms. Mata in Tess’s room. “You don’t hear her laughing,” she said. “You don’t hear her coming in to sneak the bags of chips, thinking that we can’t hear.”

“It’s just the A.C. — that’s how quiet it is,” her father, Jerry Mata, said. “That’s our new normal now.”

MARCH In the spring, the Uvalde families made frequent trips to meet with lawmakers in Austin. “If you can’t picture it, or that it could be your child, then you’re never going to step up,” Ms. Rubio said.

MARCH Katalina Mata, 2, wears a faded shirt with X.J.’s photo, on what would have been his 11th birthday.

MARCH Jackie’s family continues to maintain and decorate Jackie’s gravesite. “I’m still her mom,” Ms. Cazares said, “it’s my responsibility to take care of her last resting place.”

APRIL Mr. Cazares celebrates his 44th birthday with his family.

On Feb. 6, Mr. Mata sat in the back of his white S.U.V., watching relatives and friends trickle into the cemetery to celebrate what would have been Tess’s 11th birthday.

As the sun set, Mr. Mata joined the people gathering around Tess’s grave. Steven Garcia, whose daughter Eliahna Garcia, known as Ellie, was also killed, put his arm around Mr. Mata. “When you feel it, and it’s hitting you, just look around,” Mr. Garcia told him. “These people can be anywhere in the world but they’re right here with you and your beautiful daughter.”

Ms. Rodriguez decided to cremate her daughter, Maite, a creative and curious 10-year-old. Maite’s urn sits on an altar surrounded by photos and the shoes she had on when she was killed: Lime green Converse with a heart on the right toe. The shoes became a symbol of the tragedy when the actor Matthew McConaughey displayed a similar pair at a news conference at the White House in June, as he described Maite’s dreams of becoming a marine biologist.

At first, Ms. Rodriguez said her grief was debilitating and she struggled to take care of her two boys. She wondered how she would ever laugh again.

NOVEMBER Ms. Rodriguez carries the urn containing the ashes of her daughter on her way to the cemetery to observe the Day of the Dead.

Ms. Rodriguez thought she would keep Maite’s room as it was forever, but recently she decided to give it to her youngest son, Caleb, 12, who had been sharing a room with his older brother.

“She knows what she means to me,” Ms. Rodriguez said. “Caleb needs to know how much he means to me.”

APRIL Ms. Rodriguez recently restored Maite’s room to look like the way it did before her death.

MARCH Ms. Rodriguez and her sons Caleb, 12, and Darnell, 16, paint Darnell’s room.

MAY Ms. Rodriguez and Caleb shop for beds in San Antonio. He has been sleeping beside her since Maite’s death.

While the parents have experienced their own unique pain, their other children are learning to live without their siblings.

The weekend before the shooting, Tess told her older sister Faith, who was about to begin her senior year in college, that she wanted to learn how to swim. It is tradition for graduates of Faith’s university, Texas State, to jump into a river on campus on Graduation Day, and Tess wanted to take part.

MAY Mr. and Ms. Mata cheer for Faith at her graduation. “We lost Tess,” Ms. Mata said, but “we lost a piece of Faith, too.”

As Faith walked across the arena floor at her graduation, her parents cheered, alongside Ms. Rodriguez and the Rubio and Cazares families. They talked about how thunderstorms had been forecast for the day, and agreed Tess had kept them at bay.

After the ceremony, they walked to the river, where Faith stood at the edge of the water. Clutching a photo of Tess, she jumped.

In the spring, the Rubios, along with several Uvalde families, returned to Austin to testify before the House Select Committee on Community Safety in favor of the “Raise the Age” bill. They arrived at 7:30 a.m. wearing T-shirts with images of their lost loved ones.

APRIL Jazmin Cazares, Jackie’s older sister, cracks a cascarones egg filled with confetti on her father Javier’s head during an Easter celebration.

APRIL Friends of Makenna Elrod Seiler, who was killed in the shooting, celebrate what would have been her 11th birthday at the cemetery.

APRIL An event held in honor of Makenna at the Uvalde County Fairplex.

After waiting 13 hours, Ms. Rubio was the first to testify.

“Did you think we would go home?” she asked the committee members.

APRIL Caitlyne Gonzales, who lost many of her friends in the shooting, sings and dances to Taylor Swift songs at Jackie’s grave.

A few weeks later, the families crammed into a fluorescent-lit committee room for a vote on the bill. Two Republicans broke with their party, ensuring the bill would pass out of committee. The room erupted in applause and tears.

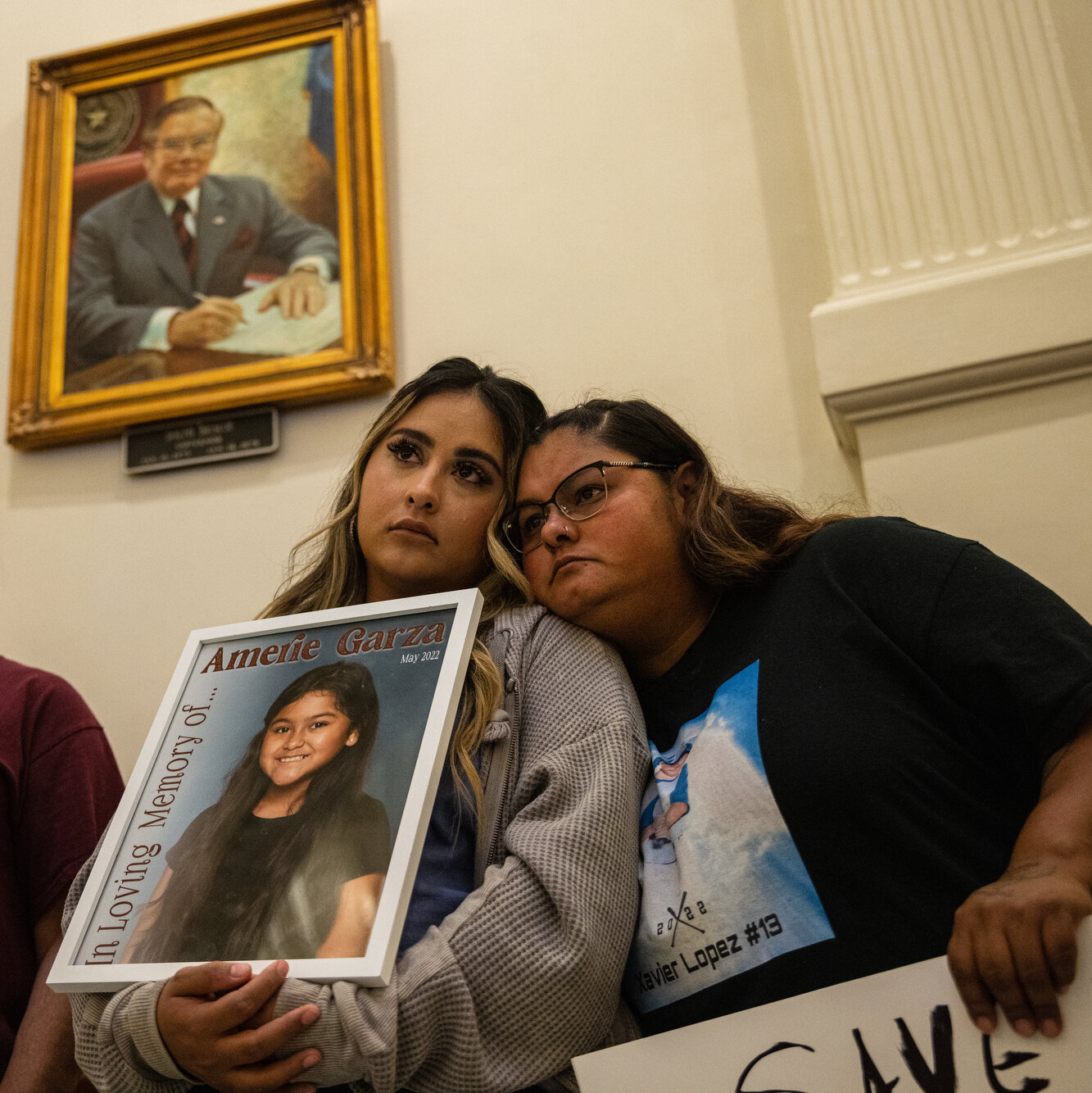

MAY Ms. Martinez and Kimberly Garcia, mother of Amerie Jo Garza, with a group of Uvalde families at the Capitol in Austin on the day the “Raise the Age” bill was voted out of committee.

MAY Angel Garza, Amerie Jo Garza’s stepfather, testified in Austin: “I had no idea that ‘I love you, Daddy’ would be the last words I would ever hear come out of her little mouth.”

APRIL Ms. Rubio sits next to her husband as she testifies before the House committee.

In the end, the bill did not reach the floor, because of Republican opposition. Still, the families said they felt they had shown that progress toward gun legislation could be made in Texas.

MAY Ms. Rubio sits in front of Lexi’s cross outside Robb Elementary School. Earlier in the day, she and other relatives of victims were allowed to enter the school for the first time since the shooting.

MAY Ms. Rubio walks outside Robb Elementary School after visiting the school.

Ms. Rubio and her husband, Felix, drove straight to Uvalde, arriving at the cemetery just after sundown. All Ms. Rubio wanted to do, she said, was lie on top of Lexi’s grave. The ground in front of the headstone was wet from the sprinkler, but she lay down anyway, letting the cool water soak into her yellow shirt that read “Lexi’s mom.”

“We did it,” she whispered. “You did it.”

Read the full article Here