American who cooked up frozen foods

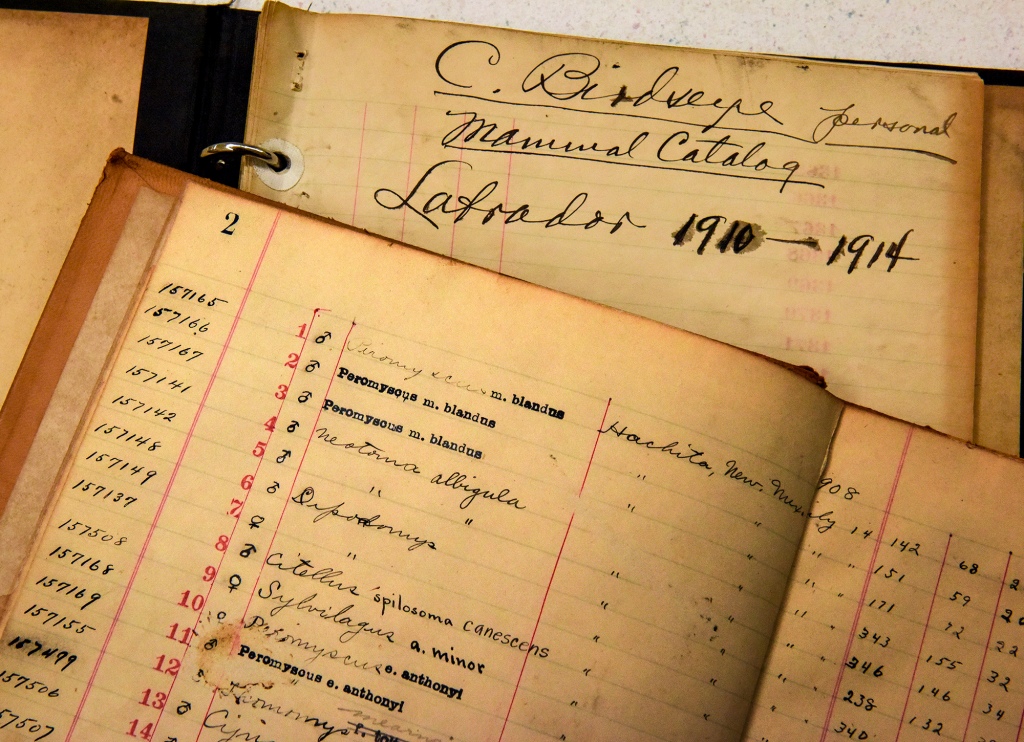

Clarence Birdseye proved you can’t judge a book by its cover.

The Brooklyn native and frozen food pioneer looked scholarly in his spectacles as if he belonged at the head of a college lecture hall.

He was actually a college dropout. And instead of lecturing scholars, he lived a life of adventure in remote areas of the world, from the frigid coast of Newfoundland to the steamy sugarcane plantations of South America.

He craved the outdoors and loved hunting.

Birdseye, among many other quirks, possessed a voracious appetite for harvesting and eating anything that walked, waddled, chirped, crawled, swam, or slithered.

In his years of exploring Labrador, Canada, or working for the U.S. government in the American West, he trapped and cooked mice, chipmunks, porcupines, otters, and rattlesnakes, to name just a few of his unusual edibles.

He raved about sherry-brined lynx and the “fine” taste of gull gravy.

Birdseye ate anything that walked, waddled, chirped, crawled, swam or slithered.

“I arrived by dog team at the North West River,” he wrote in one notably enthusiastic account of his carnivorous Canadian diet.

“And after thawing out, sat down to one of the most scrumptious meals I ever ate. The pièce de résistance was lynx meat, which had been soaked for a month in sherry, pan-stewed, and served in brown gravy.’”

Birdseye’s keen taste buds wound up reshaping the way Americans shop, eat — and even plan for disaster.

He founded Birdseye Seafood Inc. in 1924, pioneering and patenting new ways to both flash-freeze and market food for American consumers.

There’s a good chance you even have frozen vegetables bearing his name in your freezer right now.

Birds Eye — two words — is a prominent label in the frozen food aisle of American and British supermarkets, owned today by international powerhouse Conagra Brands.

The appeal of frozen foods was evident during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 when consumers stockpiled long-lasting sustenance for the unknown days ahead.

“The category rang in $65.1 billion in retail sales” in 2020, the American Frozen Food Institute reported last year — representing an incredible 21% increase over sales in 2019.

‘An odd sort of guy’

Clarence “Bob” Birdseye was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Dec. 9, 1886, to attorney Clarence Frank and Ada Underwood Birdseye.

His family moved to Montclair, N.J., when he was a teenager. High school cooking classes there fueled his innate interest in food.

Frozen food rang in $65.1 billion in retail sales in 2020 — an incredible 21% increase over 2019 sales.

“At the age of 10 he was hunting and exporting live muskrats and teaching himself taxidermy,” NPR wrote in a 2012 biography.

“He studied science in college but had to drop out for financial reasons. Forced to support himself, he joined various scientific expeditions that took him to remote places, including Labrador, where he spent several years in the fur business.”

Celebrated food historian and Birdseye biographer Mark Kurlansky also told Fox News Digital, “He was an odd sort of guy who had an impact on a lot of different things, including a huge influence on American food.”

“He was a product of the industrial revolution and thought everything, including food, should be industrialized.”

The author was inspired to write about Clarence Birdseye after the innovator made frequent appearances in many of Kurlansky’s other works, including his landmark food history, “Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World.”

Kurlansky wrote two books about him: “Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man” in 2013; and, for middle-school students, “Frozen in Time: Clarence Birdseye’s Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food” in 2014.

Yet Birdseye’s interests and inventions extended far beyond food, Kurlansky said.

“Birdseye was a product of the industrial revolution and thought everything, including food, should be industrialized.” — author Mark Kurlansky

He patented the reflecting lamps commonly used on job sites today. He helped the federal government combat Rocky Mountain spotted fever by showing that it was transmitted to humans through animals. Later in life, he also found a new adventure in Colombia, developing a process to turn sugarcane residue into paper.

Birdseye developed some 300 patents and inventions in his lifetime, Kurlansky said.

None had more impact on the nation, however than his work in frozen food.

Inspired by Inuits

Birdseye’s Eureka moment came during his dog-sled expeditions across Labrador.

He noticed that native Inuit fishermen harnessed the power of wind and ice to flash-freeze their catch.

“Fresh food was a very urgent problem in Labrador,” Birdseye wrote, in an oft-repeated account of his work.

“I found that foods frozen very quickly in the dead of winter kept their freshness as long as they were held at a low temperature.”

The secret was to replicate the flash-freezing process far from the icy shores of the Canadian coast.

“Birdseye, the biologist, saw that the fish was frozen too quickly for ice crystals to form and ruin their cellular structure,” writes the Lemelson-MIT Program, an academic organization devoted to cultivating inventors and innovators.

“Birdseye, the businessman, saw that the public back home would gladly pay for such frozen foods if he could deliver them. He returned to New York and, in 1924, founded Birdseye Seafoods, Inc.”

He set up the business, now General Seafood Corp., a year later in Gloucester, Mass., to be near one of the nation’s most prominent and productive fishing ports.

He developed a process that would rapidly freeze fish and vegetables.

“In the case of fish or meat,” the application stated, “slow freezing disrupts the cells of the animal tissue, with loss of the pristine qualities and flavors and rapid deterioration after thawing.”

His rapid-freezing process, though, ensured “the pristine qualities and flavors of the product are retained,” as he wrote on a 1927 patent application.

Chance encounter changed food industry

He was desperately lacking capital, however, when a chance encounter with business tycoon Marjorie Merriweather Post changed his fortunes.

The encounter changed the global food industry.

Birdseye’s patented flash-freezing process ensured that “the pristine qualities and flavors of the product are retained.”

The post had inherited Postum Cereal Company from her father in 1914. It’s known today as General Foods. She was a hugely influential businesswoman.

Among other notable accomplishments, Post built a mansion in Palm Beach, Fla., in the 1920s that she dubbed Mar-A-Lago.

Post happened to be sailing through Gloucester in 1926 when she discovered Birdseye’s frozen food company, at least according to company legend.

The deal in 1929 gave Birdseye the resources needed to bring frozen food to the American consumer.

Details of the story are sketchy, writes Kurlansky in “Frozen in Time.”

What’s not disputed is the result: Birdseye’s “company was of obvious appeal to the Postum Cereal Company. General Seafoods had developed the ideas and technology for an entirely new food industry,” the author writes.

“Eventually, Postum secured [Birdseye’s] company for a record $22 million.”

The deal in 1929 gave Birdseye the resources needed to bring frozen food to the American consumer.

Birdseye improved health of the industrialized world

Clarence Birdseye died on Oct. 7, 1956, at a home he kept at the Gramercy Park Hotel in Manhattan.

He spent his final days, after a life of adventure and innovation, battling a heart ailment in the city in which he was born.

“We can say that Clarence Birdseye has indirectly improved both the health and convenience of virtually everyone in the industrialized world”

He was lauded for his vision and ability to turn his ideas conceived on the ice of Labrador into an international food-industry empire.

“At the start, he could afford to spend only $7 on equipment, including an electric fan, ice, and salt.

Later, a friend lent him the corner of an ice house to carry on his work,” The New York Times wrote in its obituary of him.

“After his return from [from Labrador], Mr. Birdseye began the experiment that led to the development of his [flash-freezing] process. The development not only brought a fortune to Mr. Birdseye but helped revive the Massachusetts fishing industry.”

Frozen food today is a goliath of global consumer culture, with $252.2 billion in revenue in 2021, as Polaris Market Research reported in June.

The research company predicts global frozen food sales to reach $389.9 billion by 2030.

Birdseye “is credited with increasing the quality of the American diet by providing high-quality foods for long-term preservation without drying, pickling or canning,” proclaims the Inventors Hall of Fame, which inducted the innovator in 2005.

“Today, we especially appreciate that Birdseye’s process, still basically in use, preserves food’s nutrients as well as its flavor,” proclaims the Lemelson-MIT Program for innovators.

“In fact, we can say that Clarence Birdseye has indirectly improved both the health and convenience of virtually everyone in the industrialized world.”

Read the full article Here