An experimental horror ARG is testing the boundaries of AI art

According to ancient Nine Inch Nails (NIN) lore, we’re living in Year Zero, which began on February 10th, 2022. It’s a period of extreme dystopia, where a fundamentalist religious government oversees an omniscient Bureau of Morality and a strange phenomenon known as “The Presence” — two massive spectral arms reaching from the sky — is spotted across the country.

Year Zero was an alternate reality game (ARG) that accompanied the NIN album of the same name, and it included events that immersed fans in a theocratic police state. It was designed by 42 Entertainment, which also made Halo 2’s I Love Bees ARG and Last Call Poker for Activision’s Gun. The game began in February 2007 at the tail end of a “golden age” for commercial ARGs, which included an Audi campaign, ARG companions to major TV shows, and an “interactive clothing” company. Most of the time, these were marketing projects, which Trent Reznor found frustrating for Year Zero. “It‘s not some kind of gimmick to get you to buy a record — it is the art form,” he said at the time.

The most evocative Year Zero imagery came from designer / photographer Rob Sheridan, the band’s longtime art director who also worked with Reznor on its mythology. (Sheridan stopped working with NIN in 2014.) NIN fans followed breadcrumbs like USB sticks stashed in concert bathrooms, images hidden in song files, and cryptic messages on T-shirts. These were the days before Twitter, before AI as a Service, and before the general public became inured to the idea of mainstream social media — a necessity or utility for modern life today — as a vehicle for fiction.

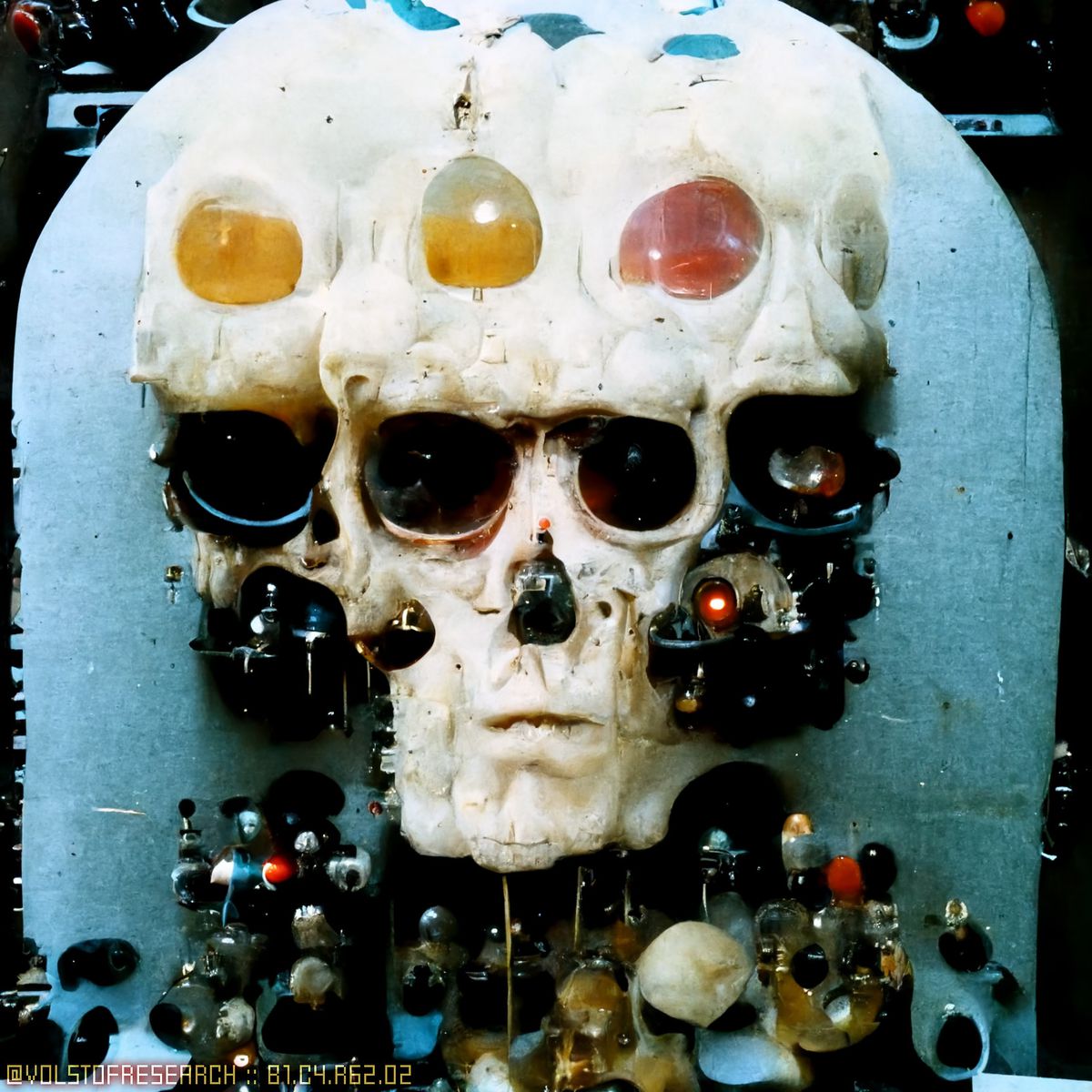

On March 29th, 2022, an enigmatic tweet appeared from the Volstof Institute for Interdimensional Research (VIIR), followed by eerie images of a forgotten lab filled with organic horrors pushing through from another dimension. This was the beginning of Sheridan’s own ARG experiment using AI art to flesh out a mix of cosmic horror and alt-history science fiction. VIIR invites “players” to examine documents taken from the fictional institute, founded in 1958 by a physicist named Florian Volstof. Volstof studied “soft places” of interdimensional bleeding and tried to communicate with strange organic beings through electronic hardware, until one day, the whole place was incinerated. The “player” is part of a diehard community who wants to figure out what happened to the lab and its unknown location.

The concept for VIIR started when Sheridan was invited to the early beta phase of a new AI art service called Midjourney, which has since become a favorite tool for artists and creators on Twitter. “I was talking to [the Midjourney bot], for lack of a better way to explain it,” he says of his early experiments with the Discord-based text-to-image generator, “and it was generating stuff that felt like it was coming out of my imagination in crazy ways and it spurred this whole project out of it.” Excited by this new frontier, Sheridan set about trying to contextualize this technology, to figure out how he could use it beyond making cool pictures. The idea of a Twitter-based ARG isn’t new, but VIIR is one of the first projects to harness AI art in a meaningful way — and arguably the first to showcase what Midjourney could do in the realm of horror.

Image: Rob Sheridan

Image: Rob Sheridan

The VIIR documents are a fantastical window into weird science gone wrong: eerie snapshots of bone growths emerging from stereos; delicate jellyfish-like structures; arcane research sketches; and rooms crisscrossed with bony tendrils. There are different species of interdimensional growths — Azathrys enjoys mimicking the human skull, while Drurigu is drawn to synthesizers — that behave like fungus, taking over everything from pinball machines to Tesla coils. These are accompanied by tweets, usually snippets from scientists’ journals, Volstof’s notes, and descriptions of the latter’s increasingly deranged behavior. Each image is stamped with a short code of text and numbers — Sheridan’s only addition to the images made with Midjourney.

Sheridan, at the time, felt like he was using the software “the wrong way,” a sentiment that has since been echoed by others using AI art tools. On Discord, he noticed that most Midjourney users seemed focused on conventional ideas of art and beauty. “Most of the artists I see on it are like, ‘a child’s dream in the style of early Andy Warhol,’” Sheridan says of the early days. “And I’m like, ‘Okay, how do I get this thing to give me a mangled body with partial cybernetic parts that has tentacle monsters from another dimension growing into it in a laboratory in the 1960s and make it look like an old photo?’” Through trial and error, he found the right recipe of descriptive words to create consistent results — words like “flesh” and “body horror” and “Cronenberg.”

Absolutely stunning looks at the #MetGala2022. I know it was a controversial decision, but I think opening a portal to Hell was exactly what this year’s event needed to spice things up. pic.twitter.com/hgtYQOqEwr

— Rob Sheridan (@rob_sheridan) May 2, 2022

At first, Sheridan felt weird about the results. “I didn’t know what to do with it, because it just looked like someone else’s art,” he says, acknowledging that Midjourney, like all other AI art bots, is trained on the work of countless other artists. “I wrote something that I thought of in my head, and it gave me back a beautiful piece of art… but I don’t feel like this is something that I can claim on any level that I made.” He is, though, acutely aware of the fear that artists might have about robots taking their jobs and has come to see Midjourney as another tool that can be used to create entirely new art instead of meme-like facsimiles. Sheridan learned to develop a collaborative approach with the Midjourney bot: it works using a simple /text command in Discord, so you can describe what you want to see in whole sentences. It was still the early days — before AI art enthusiasts drowned Twitter with “this object doesn’t exist” memes and knockoff Zdzisław Beksiński paintings.

On May 3rd, 2022, Sheridan went viral with a delightfully ghoulish AI art parody of the Met Gala, the annual fashion extravaganza — considered by some as an increasingly out-of-touch circus of class elitism — to raise money for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. It was the most popular tweet in a thread called “Events From Hell,” filled with body horror takes on pop culture, including Coachella “photos.” The post “really freaked [Midjourney] out… and their response was to assert that Midjourney is not a platform for ‘gore’ or ‘shock content,’” he says.

Not long after, Midjourney expanded their list of banned terms, including “body horror,” “Cronenberg,” and “flesh” — the terms that made VIIR possible. Others also began to feel the squeeze of Midjourney’s word bans, like Zac Gorman, an artist who tweeted about Midjourney’s restriction of the words “nudes,” “erotica,” and “seductive” and another who pointed out the apparent ban of “Jinping.” Google’s new Imagen platform also stirred discussion about “wholesome” imagery as a default, as the company admits that there’s immense potential for harmful biases, as AI art models use “large, mostly uncurated, web-scraped datasets” that can “often reflect social stereotypes, oppressive viewpoints, and derogatory, or otherwise harmful, associations to marginalized identity groups.”

When reached for comment, Midjourney co-founder David Holz explains that their image creation policies must adhere to Discord’s rules, which don’t allow “real media depicting gore, excessive violence, or animal harm, especially with the intention to harass or shock others.” He adds, “We understand banning words is a blunt tool. We continue to explore better, more subtle, and expressive solutions in the future, and certainly, they will come.”

Sheridan has since branched out to OpenAI’s DALL-E 2, which has much tighter restrictions than Midjourney. (New users have to do an hour-long video chat to go over their responsibilities, and there are far more rules about what kind of content you can generate.) Right now, he’s using both Midjourney and DALL-E 2 to create composites of each platform’s output in Photoshop. “Midjourney has much more expressive, artistic interpretations that are very inspiring and have really sparked my imagination and created new ideas, but struggles with practicality, realism, and composition — but often in a good way,” he says, showing me the product of the same prompt — a photorealistic human skull — on each platform. “DALL-E 2’s outputs are very functional and direct,” Sheridan says. “There’s much less surrealness and accidental beauty, but much more practicality, realism, and composition.” Midjourney, he says, retains a sense of creativity that has made its particular aesthetic easily recognizable.

As for the idea of censorship, Sheridan feels that it’s an issue of responsibility for companies to avoid even the smallest possibility of generating a realistic murder scene or something that can be used in a crime. “[OpenAI] explained that they understand the human body is the human body, and nudity is a part of art,” he says. “But they are accountable for what their software generates, and currently they do not have enough faith in their models to guarantee that it won’t generate something harmful or illegal (they mentioned, for example, the need to be certain beyond any doubt that the system would not generate naked children by accident).” For Sheridan, these are private platforms entitled to control the kind of content allowed. “The simple binaries of Midjourney’s content policies, which last I checked basically say ‘no porn, no gore’ can tend to feel more ideological in nature, which has frustrated some artists.” He adds, “It is not a ‘censorship’ debate, no matter how much people like to throw around that word. It is, certainly, an ideological conversation about art.”

Image: Rob Sheridan

Image: Rob Sheridan

For now, VIIR fans have to wait as Sheridan works on finishing the story. He says some have asked if he’ll expand it into a game or movie. “VIIR has been on a short hiatus while I’ve been consumed with a different kind of horror: a newborn baby,” he says. He’s had to get increasingly creative with the way he talks to the Midjourney bot as some of the key conceptual terms used in the original VIIR image “recipe” are now banned. But, on the upside, he points out that more horror artists have joined up, and he’s still able to produce horror work with it. “I’m glad the aesthetic is able to thrive there even with limitations, and I hope that can continue to be the case as Midjourney evolves.”

The evolution of Midjourney’s content restrictions (and that of other private AI art platforms) will certainly have an impact on the way that people tell stories on what are seen as the best text-to-image generators we have right now. But there will always be the danger of losing more provocative bodily forms of expression (e.g., horror, sex, nudity, and kink) to corporate caution as long as these platforms remain private — or if they use apps like Discord, which have their own terms and conditions. It’s somewhat ironic to think that, while these neural networks are trained on every painting and piece of art made by humankind, it’s humans that can’t be trusted to use it to its full potential or enforce better standards of art and media literacy. There’s also the underlying current of moralism that imbues art discourse today, which, in some ways, echoes the puritanical dystopia of Year Zero — a world where art is a form of resistance, with crackdowns on “disobedience” and “subversive” materials. For now, at least on Twitter, most AI art bots are just tools to churn out memes or goofy one-sentence “what if…” scenarios that don’t warrant anything longer than a two-second glance.

Sheridan ultimately believes that AI art platforms are something to be harnessed in service of the artist. “I saw so many people who have creative thoughts and ideas but have never been able to master the technical skills of art — or have disabilities or other things that prevent them from being able to develop strong technical skills — finally able to bring their visions to life in a powerful new way,” he explains. “When you see… how much creativity it unlocks from people who were kept out of visual art for one reason or another, it’s hard not to see the net good of this tech outweighing the bad.” He does have concerns about companies trying to wholly own the fruits of their software given that these bots have been trained using the entire history of human artistry. It’s important to ensure that we also have comparable open-source alternatives that everyone can use and retain the rights to their work.

“As with any new tech that absorbs the fruits of human labor, there are plenty of valid concerns and plenty of ways it could go down some dark paths,” he says. “It’s up to us as artists to get involved, watch what these companies are doing, and really be a part of the conversation.”

Read the full article Here