Artist seeks corpse of British person to ‘sacrifice’

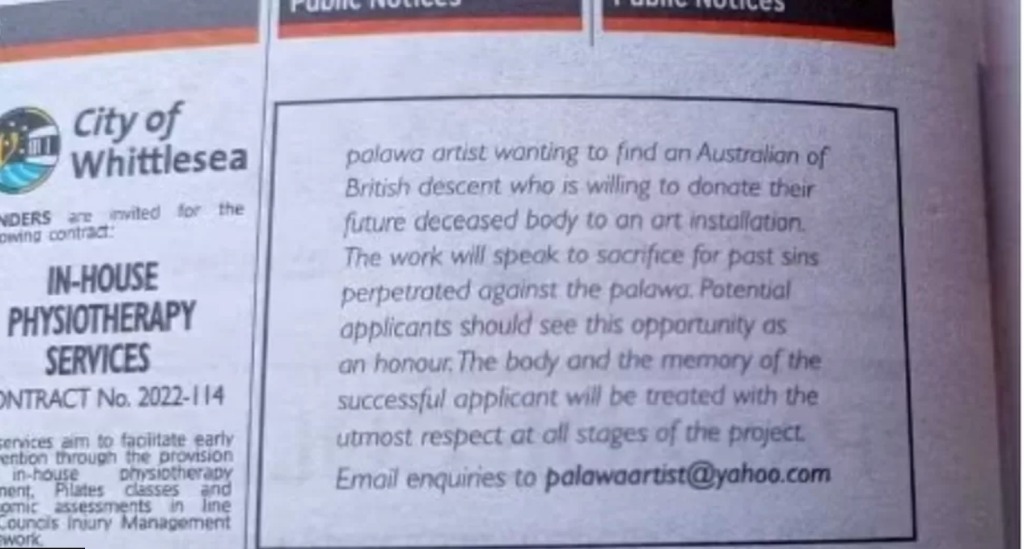

An Aboriginal artist turned heads recently when he shared an advertisement seeking the body of a British person to “sacrifice” for an upcoming project.

The ad, which appeared in Australia’s The Age newspaper, asked for a volunteer “of British descent” to contribute their future corpse “to sacrifice for past sins” against indigenous people, the BBC reported.

Palawa performance artist and playwright Nathan Maynard told the outlet that he got the idea for the offbeat request after witnessing “virtue signaling” on social media.

“With social media … everyone looks great. But lost is the fact that we’ve still got how many of our people in custody. We still haven’t got that treaty [a legal agreement with the government] in this country,” Maynard explained.

With “Relic Act,” the new work he plans to debut at an arts festival in November, Maynard said he hopes to ask viewers “what would they physically do for First Nations people in this country and around the world?”

“Would they put their body on the line if they had to? Would they protest the next time an Aboriginal person is killed in custody? Will they join our protests?” he listed.

Maynard told the BBC that he’s already had several responses to his ad, and all candidates will go through an interview and selection process.

While he emphasizes in the ad that the donated body will be treated with the “utmost respect,” he also clarifies that the project itself will address the centuries of subjugation of indigenous people by white settlers.

This includes the mutilation, theft, and display of indigenous bodies by European anthropologists, museums and other institutions over the years.

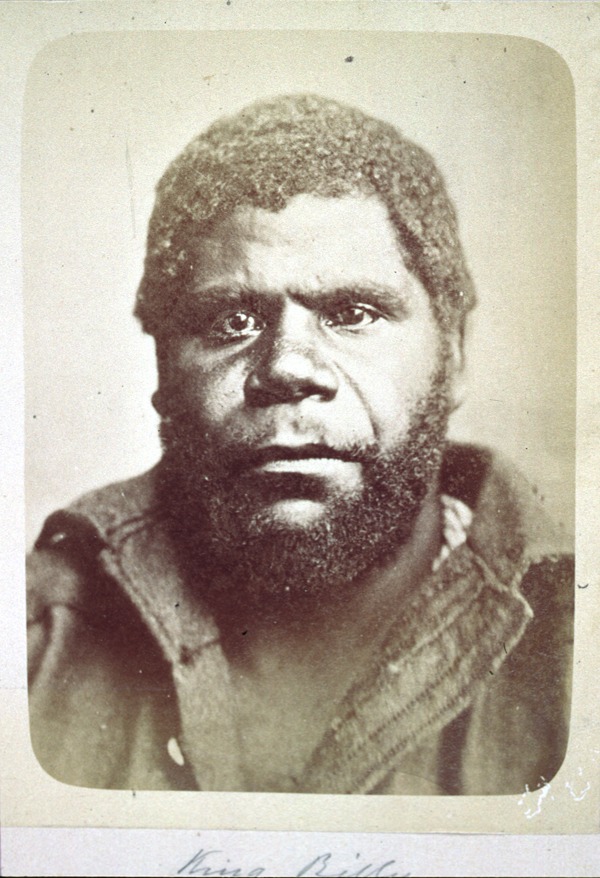

Maynard specifically referenced the story of William Lanne, an Aboriginal Tasmanian whose remains were dismembered and distributed for scientific research after his death in 1869.

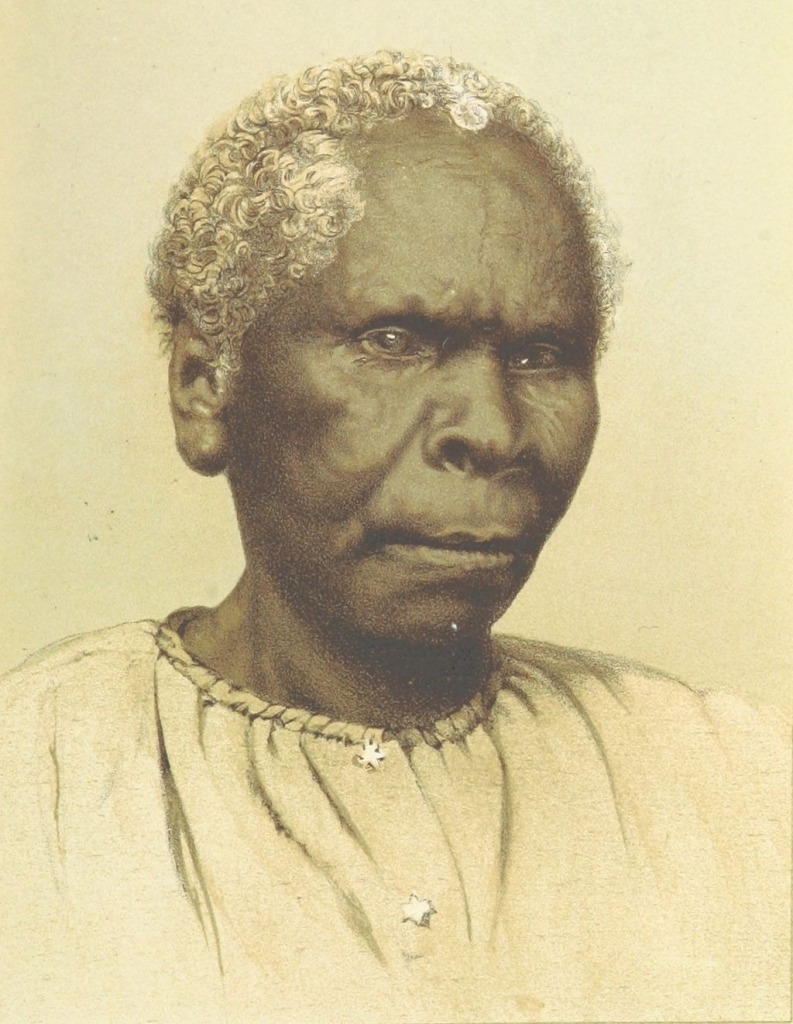

Lanne’s partner, Truganini, was also displayed in a museum after her death, despite her repeated pleas to avoid that fate. Her remains were returned to the Aboriginal community in 1976, with some additional hair and skin samples returning in 2002.

“She pleaded with everyone and the government not to do that to her. And what did they do? They waited for two years after her death, and exhumed her body and put it on display in a museum until the 1940s,” Maynard lamented.

Lanne and Truganini are just two examples of a much larger issue: According to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Studies, the remains of over 1,650 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been returned to Australia in the last three decades.

Government reports, however, indicate that as many as 1,500 bodies remain in institutional and private collections spread across 20 countries, the BBC said.

The festival where Maynard will debut “Relic Act” is even sponsored by the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), which apologized two years ago for its role in “the collection, and the trade of, ancestral remains of Tasmanian Aboriginal people.”

Even so, some question the artistic worth of Maynard’s own plan.

“I view expression through art as being a core part of being human, but when the public’s money is involved, I think there are fair questions that need to be asked,” Hobart councilor Louise Elliot said.

“In this case, how ‘healing’ is an artwork like this? I suspect it is more divisive attention-seeking than truly therapeutic and question-inducing as good art should be.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Simon Longstaff of Australia’s The Ethics Center says Maynard’s conscientiousness is a marked contrast to that of European colonizers.

“The mere fact of [Maynard] asking the question, and the debate it spurs, is already raising some really interesting questions,” Longstaff told the BBC.

“As a culture, we’ve lost the capacity to deal with genuine complexity, and to recognize that people can have different views on different topics, or different views on the same topics. I think the more that art engages us, the better we are as a democracy.

“There’s lots of mummies in museums and other bits and pieces of people that were collected and commodified in the past,” he continued.

“But where someone has actually, wilfully chosen to [donate their body] as a contribution towards not just art, but social progress, maybe this is the first.”

The TMAG also issued a statement supporting Maynard’s effort, writing that the “confrontational” work is “an important part of our commitment to [our] apology and truth-telling.

“Once the final shape of the work is clear, TMAG will continue to work to ensure the work complies with all relevant legislative requirements.”

Maynard, for his part, says he does not mind that some people are offended by his project.

“Everyone’s allowed to have opinions. I believe in what I’m doing,” he told the outlet.

“Unlike the thousands of remains of First Nations people that are displayed around the world that were cut up, dug up and sent without their permission … this person is willingly donating their body.”

His ideal donor, he said, will “understand the history and First Nations struggles.”

“I think who they are and their beliefs will really shape this,” Maynard noted.

“I want to know if they’re genuine. I want to know that they’re in it for the right reasons.”

Read the full article Here