Biden sold out Haitian democracy for a migrant deal: Ex-envoy

The Biden administration scuttled Haiti’s plans for free elections and backed a de facto dictator in exchange for his willingness to accept deportees, America’s former envoy to the country says.

Daniel Foote, the Biden- appointed former US special envoy to Haiti, says the administration has supported Dr. Ariel Henry — who took power as both acting prime minister and acting president after the assassination of President Jovenel Moise — because he was willing to accept Haitian migrants who have rushed the US border.

Henry was supposed to have organized new elections by now. But in September 2021, a large group of Haitian migrants camped in Del Rio, Texas, and images of the encampment — including border agents on horseback trying to prevent them from crossing the river — caused a political headache for President Biden.

Henry agreed to take in deported Haitians, Foote says, and the Biden administration stopped pushing for democracy on the Caribbean nation.

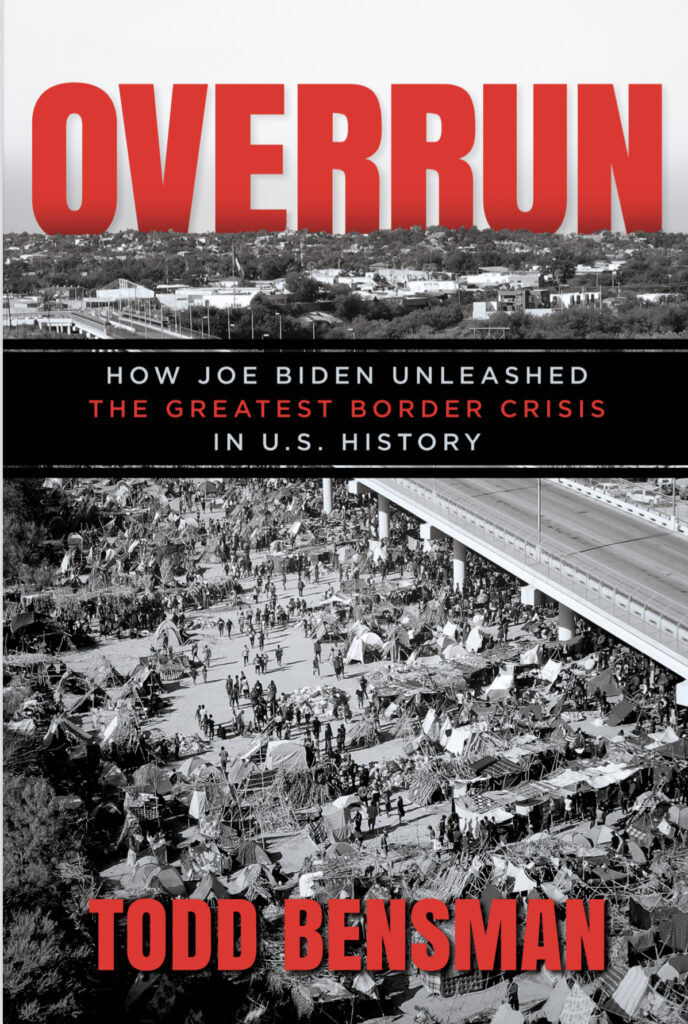

“I am confident that the chief reason they did that is his [Henry’s] malleability and the fact that he agreed that he would take all the deportees that they wanted to send. It wasn’t long after that . . . we started putting them on planes,” Foote told me in an interview for my forthcoming book, “Overrun: How Joe Biden Unleashed the Greatest Border Crisis in U.S. History.”

“The US carried out a non-democratic transfer of power. We were just kicking the can down the road so that we don’t upset the vote moving toward the midterms.”

On the morning of July 7, 2021, two dozen armed men stormed the Haitian presidential compound, killing President Moise with 12 shots and wounding his wife.

The case remains unsolved, though reports by The New York Times and CNN show that Henry is close to one of the men accused of the murder, Joseph Felix Badio. Henry has denied any involvement.

Henry was supposed to oversee the work of a “Provisional Electoral Council” that was organizing Haiti’s long overdue presidential and parliamentary elections set for November 2021.

But nearly a year later, Henry remains Haiti’s US-backed chief of state. No elections have taken place. Meanwhile, the country’s bicameral National Assembly legislature, which is supposed to provide ratifying checks or balances on executive branch power, is defunct, as is the nation’s supreme court.

Henry is a leader with no domestic checks on power — a dictator.

Foote, who was appointed envoy shortly after the assassination, thinks the Del Rio encampment is why Biden officials have looked the other way.

Starting on about Sept. 18, 2021, a massive and squalid encampment that would quickly peak at some 17,000 mostly Haitian immigrants suddenly formed on the Texas side of the Rio Grande under the bridge between Del Rio in Texas and Ciudad Acuna in Mexico.

White House advisers viewed the Texas encampment crisis as a serious political threat to Democratic prospects in the 2022 midterm elections.

The Biden administration decided to deport most of the Haitians by air from Laughlin Air Force Base outside Del Rio. But this required formal Haitian approval. Henry agreed.

The first of what would be 58 flights from the Del Rio camp carrying nearly 9,000 Haitians from Texas started landing in Port-au-Prince on about Sept. 20, and on Sept. 27, Henry abolished the Provisional Electoral Council ahead of the elections.

He could not have done such a thing without American backing and the effective anointment of Henry to indefinite power, says Foote, whose input senior State Department officials told him they did not want because the decision was already made.

On Sept. 22, Foote resigned over this undermining of Haitian democracy, his departure falsely reported as stemming only from moral objections to the air expulsions from Del Rio.

“The biggest reason” he resigned, Foote told me for “Overrun,” was the Biden government’s morally reprehensible backing of Henry to power by scuttling the democracy-restoration processes in exchange for Henry’s agreement to accept the deportation flights from Texas.

“I believe they were terrified of immigration as an issue in the midterms and beyond,” Foote says.

In its haste to scuttle Haitian democracy, Foote noted, the Biden administration showed no fealty to its most exalted immigration policy ideals: its dedication to addressing so-called “root causes” of emigration to the American border, such as poverty, violence, and poor governance.

“We’re just adding to the human tragedy in a place where the state has already failed, and creating more demand for emigration by doing that,” Foote says. “Whereas, if we did it like reasonable adults and thought through the best way to do it, we could address the drivers of emigration and minimize the amount of emigration.”

Biden also faces critics in his own party.

In March, seven US members of Congress pushed Biden to withdraw support for Haiti’s Prime Minister Ariel Henry and instead push for a transitional government.

“If we look at what are the reasons behind [the immigration], it really comes down to the political instability that’s increasing the crime going on in Haiti,” Haitian-American Rep. Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick (D-Fla.) said to Reuters.

But an agreeable strongman is preferable to an elected government that might block the flights.

As The Wall Street Journal reported last year, “Some of Mr. Biden’s top advisers, who favored the mass deportations, said images of the migrants under the bridge weeks after the chaotic withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan could add to the criticism that the administration was losing control of tough situations.”

Amid electoral setbacks in Virginia and New Jersey for Democrats at the time and the “disarray” of the Del Rio camp, The Washington Post reported, the White House found itself under pressure to “avoid further scenes of chaos at the border.” Top moderate advisers viewed the crisis “almost entirely from a political lens,” the paper reported.

And even though the Biden administration had bashed Donald Trump’s policies, it knew that air deportations were highly effective at deterring illegal migration.

By the end of September 2021, some 8,000 Haitians had been deported and the camp was mostly forgotten by the media.

The Biden administration made a show of ending the Del Rio flights under pressure from the party’s liberal progressive wing, which was outraged by them. But in December 2021, as the number of Haitians began to climb again, the administration restarted the Haitian deportation flights.

Henry was still there to accept more than 10,000 returned Haitians from January through April 2022. No new similar camp of Haitians has ever formed again. Henry still has not reestablished the Provisional Electoral Council.

Todd Bensman is a national security fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies and author of the forthcoming “Overrun: How Joe Biden Unleashed the Greatest Border Crisis in U.S. History.”

Read the full article Here