Inside the high-stakes Afghan rescue mission after Kabul fell

It was August 2021, and Afghanistan had turned into a tinderbox ready to explode in the wake of President Biden’s botched evacuation of American troops. Nezamuddin “Nezam” Nezami was an Afghan commando who graduated from the elite Q Course at Fort Bragg, in North Carolina, and did special operations work for the US military. The Taliban knew all about Nezam, who was now a marked man. Members of the terrorist regime were looking for him as he hid out in the home of his uncle. Nezam had two options: Get out of Afghanistan or get killed by Taliban forces — and possibly leave his family to face the same fate.

Nezam’s hole card was retired Lt. Col. Scott Mann. Living the good life in Tampa Bay, Fla., Mann was a highly decorated Green Beret who had parlayed his military experience into a lucrative career. Through his firm, Rooftop Leadership, he uses combat experience to help sharpen the leadership skills of corporate executives. Earlier that summer, however, Mann began receiving SOS messages from his Afghan brother-in-arms.

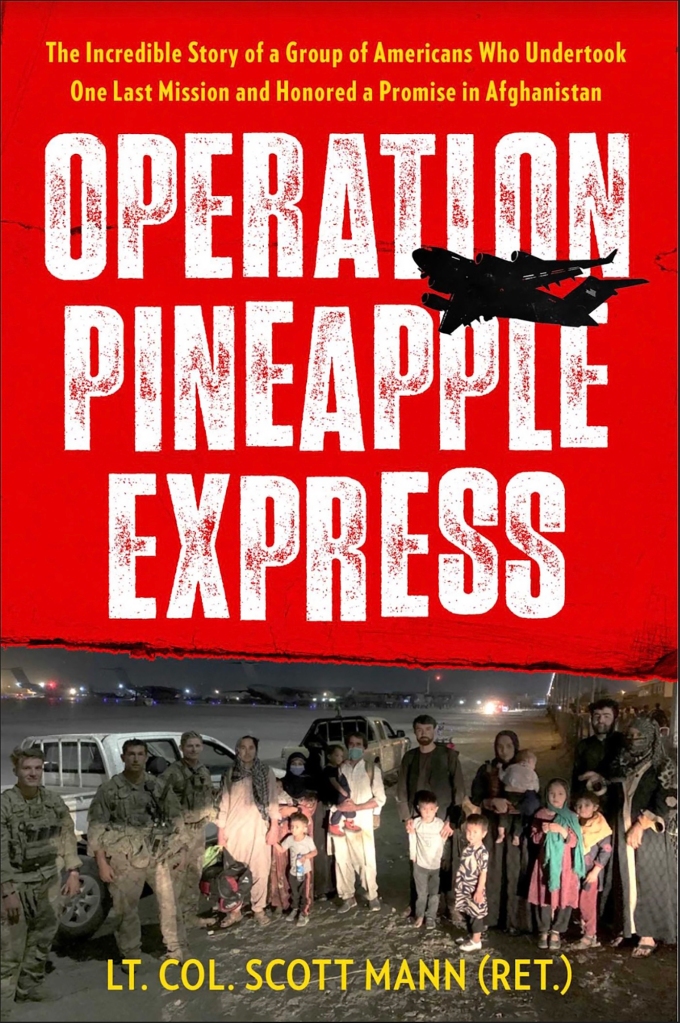

The situation sounded increasingly dire. “He made it clear that everyone was gone, he was on his own and he was not afraid to die — but he was afraid to die alone,” Mann, author of “Operation Pineapple Express: The Incredible Story of a Group of Americans who Took One Last Mission and Honored a Promise in Afghanistan” (Simon & Schuster), told The Post.

Then, on Aug. 15, Kabul fell. A visa ceased being an option as Afghanistan deteriorated into fundamentalist madness. “As that happened, whether this young man lived or died fell on my shoulders,” Mann explained. “I said, ‘The hell with it. We’ll give it a shot.’ I couldn’t leave him to die.”

Mann called in favors and contracted a crack crew of military experts from the special operations community — some retired, some still active — and, communicating by text, they hatched a plan to bring his old friend to safety. He vowed that it would be one mission for one man. “We started putting together the plan immediately,” said Mann.

“The first problem was getting him across the city because of the checkpoints. Records had been compromised. Nezam, if searched, would be found out. The Taliban guys would look at him with suspicion and ultimately kill him on the spot. He was known for being a hunter of Taliban.”

Against all odds, with encrypted text messages ricocheting around the world, they got Nezam to the notoriously congested Gate, where hundreds of desperate Afghanis jostled to get through. US military tried dispersing crowds by shooting off disorientating flash-bangs. Nezam, who lacked the proper documentation to be let in legitimately, knew how to handle the nonlethal grenades. Then he latched onto a family with the correct papers. He followed them through but still needed documentation in order to squeeze onto a plane.

Mann and his partners sent frantic messages to contacts on the ground inside Kabul Airport. On the fly, an officer there provided a randomly chosen code word for Nezam to use: “Tell him to shout ‘Pineapple,’ and we’ll know it’s him.”

It worked. Nezam got through. Before boarding, he mentioned that his wife and children had been left behind — “He always kept it quiet for fear of their lives,” said Mann, who assumed Nezam was single — they were whisked to the field and let in through a secret VIP entrance. In four days, on Aug. 19, Nezam and his family were saved from all but certain death. They were evacuated and the guys thought their work was done. Exhausted but exhilarated, they planned on returning to their regular lives. Then congratulatory messages rolled in. And the kudos were invariably laced with requests to get others out. Mann and his crew could not say no. They had already built an infrastructure for Nezam and his family. Rather than shutting it down, they birthed Operation Pineapple.

It became clear that nighttime was the right time for moving people, the only way to do it discreetly. “Pineapple” became the code word that would be shouted to get through Abbey Gate. But soon that news got out, and random people shouted “Pineapple.” It created mayhem. Further steps were required. An ingenious plan came via a crew member from Pittsburgh. He was an ex military man who taught high school history and focused on Harriet Tubman and her Underground Railroad.

Operation Pineapple proved a roaring success. Sometimes too successful. It became an obsession for those involved, eating up family time, impinging on jobs – “We were people’s lifelines,” said Mann, “but we also had had lives” – and running around the clock. “We saved 700 to 1,000 people who were in danger of being killed or arrested by the Taliban,” said Mann, adding that it all came at a price. “I put my business on hold, another guy quit his job and someone cashed in his kid’s college fund to pay for a safe-house.”

They were still going strong on Aug. 26, the day that a suicide bomber attack killed 170 Afghans and 13 American troops at the Abbey Gate. “The guy blew himself up,” said Mann. “And that was the end of us getting people out.”

Among the dead: hundreds of girls that the Pineapple group was ambitiously trying to evacuate on that ill-fated day. “I’ve heard that several people saw footage showing that quite a few young girls were killed,” said Mann. “It was so chaotic that we never ascertained what happened. But a woman [working with the evacuees] said, ‘Scott, those girls didn’t make it but you gave them one thing they they didn’t have.’ I asked what that was. She said, ‘Hope.’ That broke me. I really wanted to get those girls out.”

Looking back on it all, he is proud of what Operation Pineapple accomplished — it continued until January 3, 2022, working with humanitarian organizations “to keep people alive” if not to exfiltrate them — and frustrated by the fact that it had to be initiated in the first place. “This was an Uncle Sam sized problem, which would have been a rounding error for the government to handle,” he said. “But they didn’t want to take it on. So we tried to solve it with our cell phones and bank accounts.”

Read the full article Here