Josephine Baker was a badass resistance spy

As Josephine Baker moved through international checkpoints in Spain and Morocco, the dancer and singer teased the agents who asked to see her papers, saying they just wanted her “autograph.”

Her official story was that she was on a “tour of Spain.” She was really working as a spy for the resistance, with state secrets neatly hidden in her bra.

Baker took a gamble that no one would dare to strip-search her. She smiled her famous smile — she was at the time the most photographed woman in the world — as the documents stayed “snugly in place, secured by a safety pin.”

Baker’s role as one of the true heroes of World War II, fighting against the Nazis at great risk to herself, is detailed in the new book “Agent Josephine: American Beauty, French Hero, British Spy” (PublicAffairs) by Damien Lewis. In 1961, she received a Legion D’Honneur, France’s highest decoration for military service, for her Spain and Morocco mission, and was commended for retrieving “precious information.”

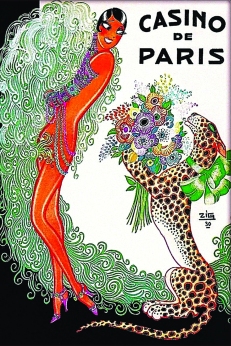

Born in St. Louis in 1906, Josephine Baker moved to France at 19. She emigrated with the hope of leaving the racism that hindered her American aspirations behind. She quickly became famous for her singing and dancing, including her beloved act where she wore only a skirt made of rubber bananas. She befriended French luminaries like the writer Colette. She bought a chateau, wore gowns by the most exclusive designers, and often walked the streets with her pet cheetah, Chiquita, who wore a diamond collar.

And for a while she was treated equally.

Once, when a visiting American seeing her dance at the Folies Bergere theater remarked, “At home a n—-r woman belongs in the kitchen,” the room fell silent in horror.

“You are in France,” the manager curtly replied, “and here we treat all races the same.”

But dark forces were rising in Europe.

In 1925, when Hitler’s “brown shirt” storm troopers were still considered a fringe group, Baker performed in Berlin to thunderous applause. When she returned two years later — after Hitler had gained prominence with the publication of his book “Mein Kampf,” which denounced black people as “half-apes” — the response was very different. German and Austrian newspaper headlines denounced her as a “black devil” and a “jezebel.”

“How dare they put our beautiful blonde Lea Seidl with a Negress on stage?” asked one paper, while another claimed “the convulsions of this coloured girl” would undermine Dresden’s sense of dignity. The mobs were such that Baker feared for her life.

Ten years later, Baker’s face adorned the cover of a 1937 brochure denouncing decadent artists issued by Joseph Goebbels, the chief propagandist for the Nazi Party. That same year, Josephine married the Jewish industrialist Jean Lion. Her passion to fight against the Nazis — and to defend her adopted country and husband, as well as herself — grew to a fever pitch. In 1938, she declared that Nazis were criminals and “criminals need to be punished.” She claimed she would kill them with her own hands if necessary.

![Baker was not shy to call out the evil of the rising Nazi power in Germany, declaring in 1938 that she would kill [Nazis] with her own hands if necessary.](https://mamardi.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/jobaker1.jpg)

That same year, she was approached by the Deuxième Bureau as an Honorable Correspondent, a voluntary position that involved retrieving intelligence for the bureau. It was entirely unpaid, as was typical for such a role. Throughout the war, Josephine refused to accept money for her work and sometimes resorted to selling off jewels and other assets to help finance her excursions.

Soon after she began working as a spy, Baker learned through friends at the Japanese Embassy that Japan had signed a secret anti-communist pact with Hitler. It was the first of many pieces of information she’d convey back to the bureau. Shortly after that, she informed the bureau that — through friends at the Portuguese embassy — she had learned that Germany planned to occupy neutral Portugal to use their ports. She quickly became one of France’s most valuable assets. Espionage gave Baker the ability, as Lewis puts it, “to strike back, without necessarily ever needing to draw blood.”

When the war came to France in 1940, Josephine’s glamorous country home — the Château des Milandes in the Dordogne region — became a base of operations for the local members of the resistance, as well as refugees, including a Belgian Jewish couple whom Baker sheltered there. A radio transmitter was installed on the tower for contact with Britain, and the cellar was filled with weapons for the resistance. When German soldiers stopped by to investigate after receiving a denunciation, Baker assured them that she was merely a dancer.

Though, she informed them pointedly, “I would not have the heart to go on stage when there is so much suffering.” In fact, Baker did go on stage throughout the war — she just wouldn’t perform for Nazis.

As a star performer, Baker had a cover that allowed her to easily travel to other countries — from Portugal to Spain to Morocco — something most people could not obtain visas for during the occupation.

“I come to dance, to sing,” she told journalists abroad who asked her why she’d left France. She’d actually come to ferry missives, photos and documents that might be helpful to the allies, and to meet with those sympathetic to the cause of the resistance. She carried sheet music with information written in invisible ink regarding the positions of the enemy defenses in southwestern France. She stuffed notes about other important details in her lingerie. Fellow agents would travel with her, pretending to be her “tour manager.”

Throughout the war, she worked with “Berber leaders, Rif chiefains [from the Northeastern region of Morocco], Arab dignitaries, American troops both black and white, (former) Vichyites, plus the Free French forces.” Even as her friends were murdered by Nazis or sent off to concentration camps, Baker maintained her cool. When she performed for American troops in Northwestern Algeria, she survived enemy fire by diving near the buffet tent. A Texan soldier crawled over on all fours with a bowl of ice cream for her, which she happily ate.

Afterward, she joked, “Me, belly down, amongst soldiers from Texas, Missouri and Ohio in my 1900 Paris dress, must have been an irresistibly funny sight. Mostly because I kept on eating.”

After the war, Josephine returned again to Germany in 1945. This time, she was honored at the Allied Victory ceremony at Hohenzollern Castle, the historic home of the German royal family. She took the place of honor in a country that had degraded and ridiculed her only a few years before. Then, she performed for the survivors of Buchenwald death camp who were too feeble to leave the prison. Although the camp was riddled with typhus and still littered with bodies, and Baker was in poor health, she still found the strength to sing a number called “In My Village” about the simple pleasures of home.

Even after France was liberated from the Nazis in 1944 and the war ended the following year, Baker never stopped fighting for equality for all people.

“She would never forget the lesson of the war years: freedom must be fought for, every day,” writes Lewis.

She died in 1975 at the age of 68. While she danced right up until the day before her death in a revue at the Bobino Theatre in Paris celebrating her 50 years in show business, she said that “the war years” had been the highlight of her life.

“I gave my heart to Paris, as Paris gave me hers,” she said onstage at the Revue’s opening night.

In 2021, she was given her greatest honor — admission to the French Pantheon, which recognizes only the greatest figures in French History, such as Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Marie Curie.

She is one of only five women to earn a place there.

Read the full article Here