King Curtis was the greatest musician you’ve never heard of

As more than 1,000 people began arriving for the noon service at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue and East 54th Street, they couldn’t help but see the sign at the entrance. “Soul is the feeling of depth, the ability to reach someone. It’s being part of what today is all about . . .” the message began.

It was signed at the bottom, “Aretha Franklin.”

This was a memorial service for musician King Curtis, who had been stabbed to death at his Upper West Side doorstep days earlier, succumbing on Friday, Aug. 13, 1971.

The passage of time may have made the name King Curtis less familiar to the general public. But the music he made — from the staccato “chicken scratch” sax solo that propelled The Coasters’ 1958 hit “Yakety Yak” to the top of the charts to his soulful saxophone wail that gave added oomph to Aretha Franklin’s signature hit “Respect” — lives on.

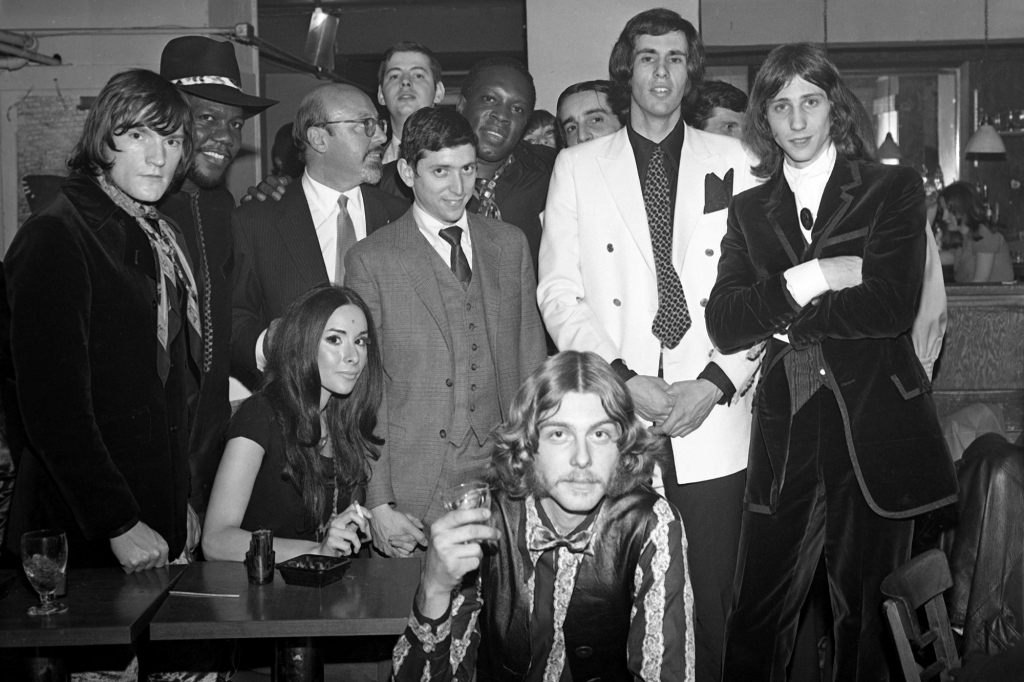

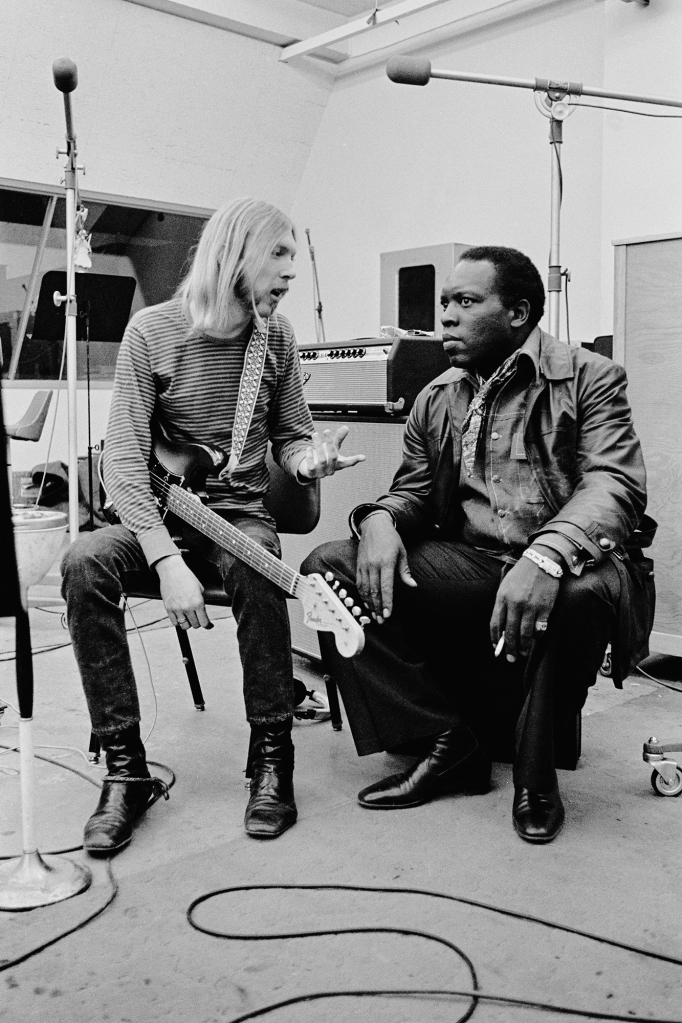

Curtis was the musical director and bandleader for Franklin, who he referred to as his “little sister.” He and his band opened for the Beatles at Shea Stadium and the rest of their 1965 US tour. He played with pal Sam Cooke, who gave a shoutout to his friend’s song “Soul Twist” on “Having A Party.” He brought his unique sound to hundreds of tracks by singers ranging from Wilson Pickett to Andy Williams. Curtis recognized the talent in Jimi Hendrix early on and hired him for his band, the Kingpins, in 1966. Duane Allman played with — and became best friends with — Curtis. In 2000, King Curtis was posthumously inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as a sideman.

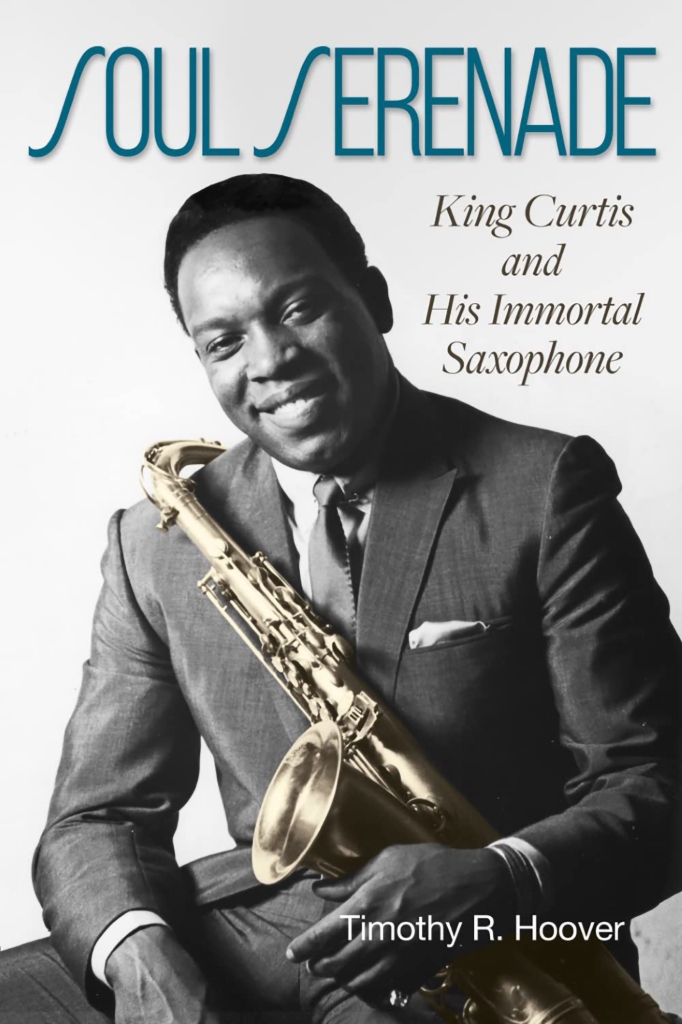

A couple of decades later comes the new, and long-overdue, biography “Soul Serenade: King Curtis and His Immortal Saxophone” (University of North Texas Press) by Timothy Hoover.

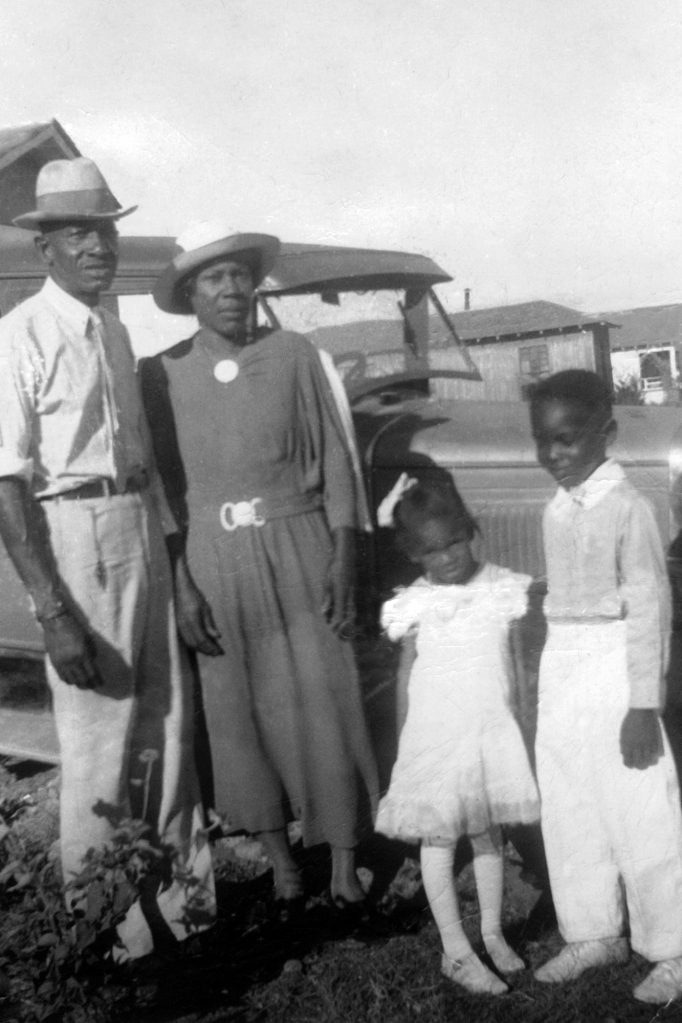

The Texas-born sax player, bandleader and record producer was born in 1934 and adopted as an infant by Josie and William Ousley — his father played guitar in church. Curtis got his first saxophone when he was 11. And as a high-schooler, he began playing at local Fort Worth spots, even the all-white nightclubs.

In the summer before his senior year, Curtis visited an uncle in New York City. At 6-foot-2 and over 200 pounds, “he was not intimidated by his new big city surroundings and fast-paced lifestyle,” Hoover wrote. “Curtis wanted to see how he stacked up against the established New York competition. What better way to find out than entering Ralph Cooper’s Amateur Night at the famous Apollo Theatre?”

He won the heated competition at the Apollo his first two times onstage. And he quickly scored work at a recording session in the city, the first of many. After returning home and graduating in 1953, Curtis turned down music scholarships to college in Texas and adopted New York City as his home.

As his live gigs and session work continued to to increase, Atlantic Records’ president Ahmet Ertegun recommended Curtis for the Coasters’ new record. Following his 1958 “Yakety Yak” success with the group, Curtis led the house band at the famous Harlem nightclub Small’s Paradise, where he’d frequently spend late nights with club owner Wilt Chamberlain in the back room “with all sorts of celebrities until 3, 4 or 5 in the morning playing dice, gambling and that sort of thing,” wrote Hoover.

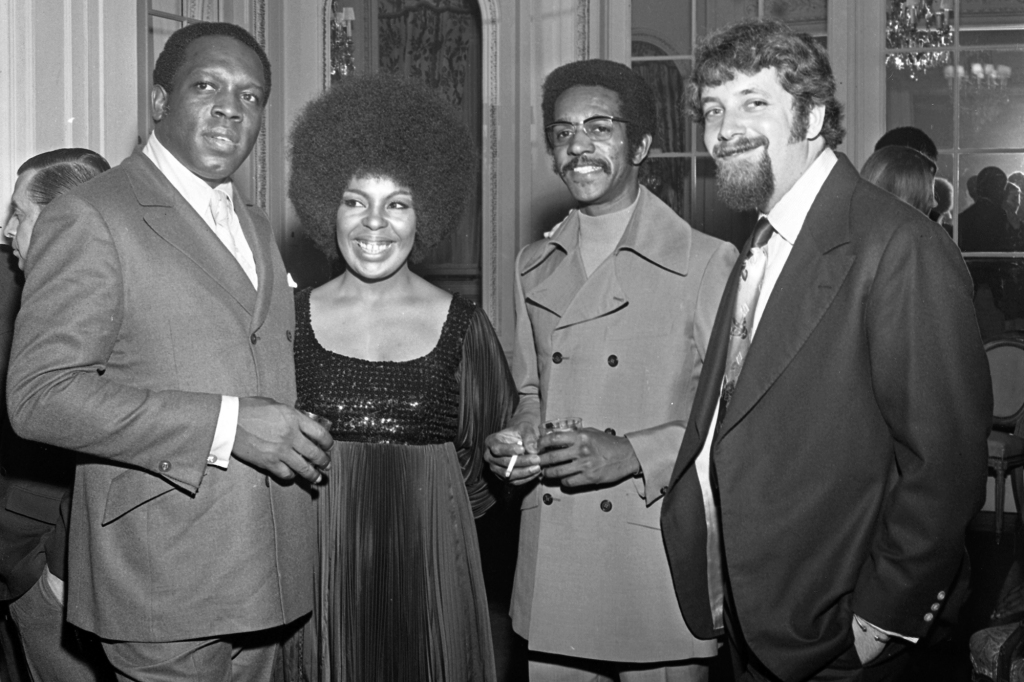

King Curtis was magnetic — he was at the center of a music scene in the ’60s that included R&B, soul, jazz, pop. People gravitated toward him.

“It was his personality, tied into his appearance,” Hoover said in a phone interview. “He was a stickler for always having a tie, making sure his shirtsleeve cuff came past the sleeve of his coat. He always had a gold wristwatch on, liked to wear big furs and big suits and just liked to play the big bandleader about town.”

Curtis and his wife, Ethelyn Butler, had a son, Curtis Jr., in 1959. The couple formally separated in 1964, but never divorced. Curtis took up with Modeen Broughton, a model and events planner, and the couple was living together in a condo on West 96th Street in Manhattan. Later, Curtis purchased a limestone building at 50 W. 86th Street, near Central Park. “He was redoing the place,” said Hoover, adding that he’d often have musicians over to work on some songs with him, or have friends over to hang out.

It was there, on a warm August night in 1971, that Curtis was killed.

There was a swimming pool and a pool table in the basement of the building. Curtis and Modeen and friends were hanging out there when the power went off — a new air conditioning unit in the building kept tripping the circuit breaker. Curtis grabbed a flashlight, and he and his personal assistant Norman Dugger had to walk outside to access the building utility room, where they could check the fuse box.

They found a young man arguing with a girl on the stoop. “Curtis was incensed at this uninvited company,” wrote Hoover. “You better get your trash out of here,” Dugger recalls Curtis yelling. The larger man was further agitated at the response of “No hablo Ingles.”

“Curtis was so angry,” Dugger recounts to the author. “And he raised his hand and broke the flashlight right over the kid’s head! Man, batteries were flying everywhere . . .”

The two men fought. “Then King stumbles back and pulls a knife outta his chest. He grabs the guy and slashes him three, four times — then falls down on the ground.”

His friends rushed him down to Roosevelt Hospital with a police escort leading the way.

Just after midnight, he was pronounced dead. But meanwhile, another man was wheeled into the emergency room accompanied by two cops. Dugger recognized Curtis’ assailant. He told the police, and the perp was arrested on the spot.

At the funeral service, Rev. Jesse Jackson gave a sermon. Stevie Wonder sang a revised version of the hit song “Abraham, Martin and John,” adding, “and now King Curtis.” Afterward, he gave 11-year-old Curtis Jr. his harmonica.

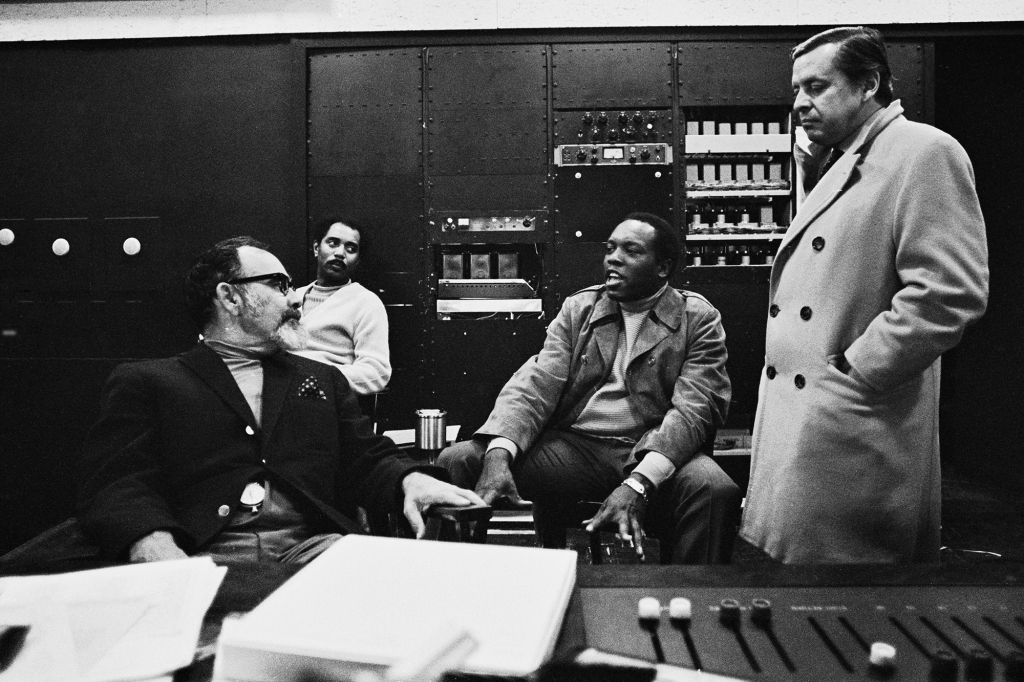

King Curtis was perhaps at the peak of his career that summer. He had backed Franklin at her landmark shows at the Fillmore West earlier that year, with the live performances turned into a pair of highly acclaimed records of Franklin’s set and of his own. And just a few weeks before his death, Curtis was at the Record Plant studio in Manhattan with his friend John Lennon to record for a couple of tracks for Lennon’s “Imagine” album. Lennon, would be murdered nine years later 14 blocks south of where Curtis was killed, also outside of his own home.

The service for Curtis concluded with an emotional Aretha Franklin singing the gospel song “Never Grow Old.”

King Curtis was 37.

Read the full article Here