‘My skinny, sexist, exciting days as a TWA flight attendant’

Ann Hood was 11 years old, living in a small Rhode Island town in the 1960s, when she picked up a book called “How to Become an Airline Stewardess.” The manual described breakfasts in New York, dinners in Rome and boyfriends in every city in the world.

“The airline stewardess leads a life completely different from the routine of any other working girl,” its author declared. To Hood, this sounded just great.

Her seventh-grade guidance counselor thought otherwise. “Ann, smart girls do not become airline stewardesses,” he sniffed.

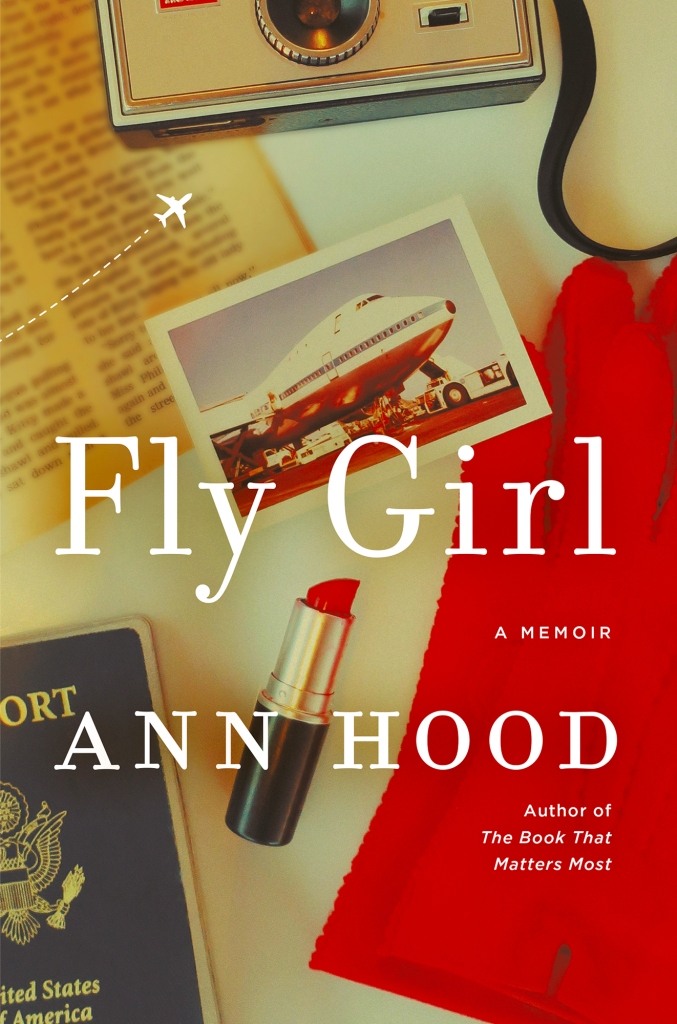

Hood proved him wrong. Not only would she work as a flight attendant for TWA, but she would also become an author in the process, writing her first novel while logging long hours up in the air. Her new memoir, “Fly Girl” (W. W. Norton & Company), chronicles her time flying the friendly skies from 1979 to 1986.

It was, she writes, “one of the most demanding, sexist, exciting, glorious jobs a person can have.”

Hood was born in West Warwick, RI, in 1956. During her senior year studying English at the University of Rhode Island, she finally fessed up to her dream of becoming a flight attendant. “Do we get free tickets?” her initially skeptical father asked. When Hood said yes, he gave her his blessing.

Her first interview, with American Airlines, consisted solely of walking back and forth across a room as a dour woman appraised her legs. Her six-week training for TWA, however, proved harder than college.

“People were sent home every day because they failed written tests, showed a bad attitude, got too frightened during emergency procedures, or just got homesick,” Hood writes. She learned to “evacuate seven kinds of aircraft,” deliver babies, administer oxygen, apply eyeliner and lipstick without a mirror, extinguish fires, mix cocktails, “brush off passes from male passengers” and “make a baby rattle out of two plastic cups and a couple TWA propeller-shaped swizzle sticks.”

Hood passed with flying colors, and was sent to Boston. New hires endured a grueling six-month probationary period, where they had to fly “on reserve,” without a set schedule, ready to take flight at a moment’s notice. Instructors popped up on flights to quiz them about safety and service, or met them after landing to measure their hemlines and even weigh them. “Other than missing a flight, the number-one reason new hires got fired . . . was for being overweight,” Hood writes.

New attendants had to maintain their hiring weight, even if many of them, like Hood, had starved themselves before their final interviews so they would look as attractive as possible in TWA’s chic Ralph Lauren uniforms. So Hood — 5-foot-7 and 120 pounds — and her five flight-attendant roommates would sit in the sauna of the YMCA, “trying to sweat off the pounds.” They took diuretics, tried crazy diets and sometimes “just drank water until a pound or two came off.” One of her roommates passed out from hunger while packing for a trip. (The weight requirement was eliminated in 1991.)

“The doorman was always calling us with flower deliveries,” Hood writes of the bachelorette pad she shared with her co-workers. Men showed up, and the girls “went on their boats and zipped around in their Porsches or sat in their box seats at Fenway Park” — that is until their pagers buzzed, whisking them away to “Vegas or Wichita.”

Flights were simultaneously thrilling, challenging and grueling. Hood describes finding “a pile of toenail clippings” in a seat pocket, administering oxygen to a passenger having a heart attack, and making an ice-cream sundae for Richard Gere in first class (asking if he wanted nuts “still makes me blush,” she writes).

She witnessed a young woman die of a drug overdose, comforted countless grieving passengers on their way to funerals and once watched the mile-high club in action, as every man in first class one by one got up to visit a woman in the bathroom during a trip from Boston to LA. “How did they know she would go along with that?” a naive Hood asked her fellow attendant later that night over margaritas. “They hired her,” he said laughing. “She was a prostitute.”

Eventually, she got to work on international flights. She wept seeing the pyramids in Egypt, and enjoyed a 24-hour romance during a layover in Portugal. “One of the biggest love stories” of her life began “at 35,000 feet,” with an aspiring actor with whom she would move to Greenwich Village.

Hood eventually wrote and sold her first novel, “Somewhere Off the Coast of Maine” — based on her brother’s group of college friends. She went on strike in 1986, after TWA’s new owner Carl Icahn announced a 44% percent pay cut for flight attendants, and was eventually fired. She worked at Presidential Airlines for a year, but hung up her uniform shortly after her book was published in 1987.

Hood married, had children, wrote and taught. Yet she never stopped romanticizing air travel.

She writes: “Being a flight attendant brought me everything I had dreamed.”

Read the full article Here