No Box to Check: When the Census Doesn’t Reflect You

Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, Amazigh, Arab, American.

These are just a handful of ways that thousands of people who responded to a New York Times callout described themselves. The answers were as diverse as the group of individuals behind them. People with roots in the Middle East and North Africa, often abbreviated as MENA, represent a multitude of cultures, religions and languages. And they all have different viewpoints about how they fit into the American mosaic.

Accounting for MENA identity in the United States has become particularly relevant this year. The 2024 presidential election could hinge on a handful of swing states like Michigan, where Arab American voters turned out decisively for President Biden in 2020. But Mr. Biden has faced mounting frustration from Arab Americans and others within his party for his support for Israel in the war in Gaza.

While people of MENA heritage are by no means monolithic, they do share one common experience in the United States. On official forms, most don’t see themselves represented among the check boxes for race or ethnicity. With few good options, many end up being counted as “white.”

A decades-old federal guideline defines “white” as anyone with origins in Europe, North Africa or the Middle East. In the 2020 census, “Lebanese” and “Egyptian” were offered as examples for the “white” box on the race question. The other categories were “Black or African American,” “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander” and a variety of Asian ancestries.

While the Times survey and follow-up interviews — conducted from September 2022 through August 2023 — do not represent all Middle Eastern and North African voices, a vast majority of respondents agreed that the current race categories are at odds with how they identified.

“I never check the ‘white’ box. I understand why it exists, historically and logistically, but I have never identified as a white person.”

Martin Zebari, 30,

identifies as Southwest Asian

“The categories don’t speak to my identity as Arab or, more specifically, Yemeniya. I don’t walk through this world as a white person, I don’t get those privileges as a white person, I don’t have white culture.”

Samera Hadi, 33,

identifies as Yemeni American

“I am African, but I feel that checking the ‘Black or African American’ box is wrong. My ancestors did not struggle through slavery or racism. My skin color does not make me a target of racism, but I’m not white.”

Imene Said Kouidri, 48,

identifies as Algerian and North African

“You come to the U.S., and if you’re dark skinned, then you’re Black. But there’s nothing in Somali that’s ‘Black’ or ‘white.’ Sometimes I choose ‘other’ and sometimes I choose ‘African American.’ ”

Faisal Ali, 29,

identifies as Somali and Arab

“Given the choices, I would always say ‘white.’ But there are a whole bunch of qualities associated with that that don’t capture me, my identity, my background and my experience.”

Joseph Hallock, 80,

identifies as Syrian American

Community leaders have been advocating for Middle Eastern and North African to be included as an official category for years.

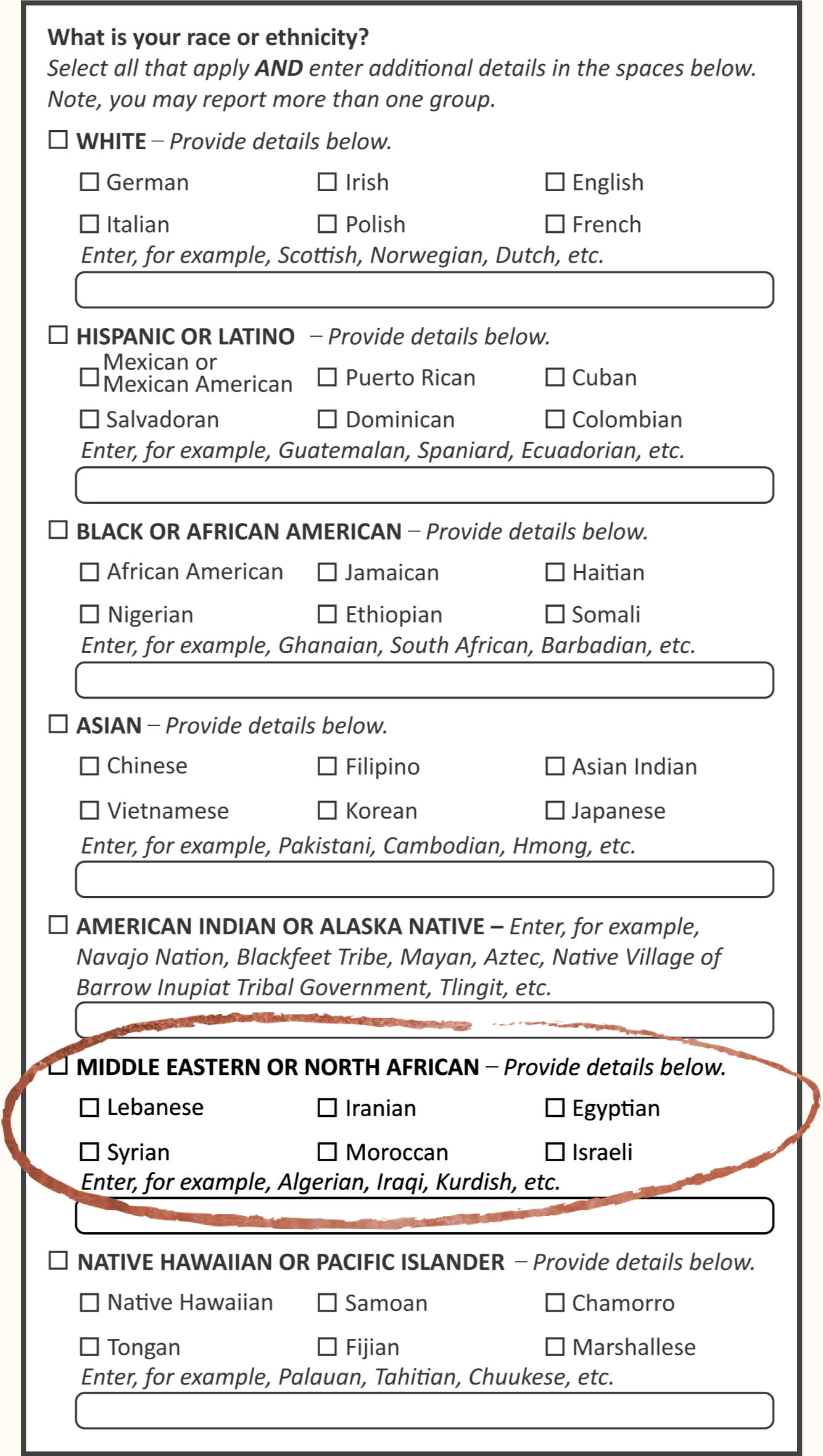

The Biden administration last year proposed removing MENA from the “white” definition and adding a “Middle Eastern or North African” box as part of a larger overhaul to combine the question of race and ethnicity on federal forms.

Take a look at a proposed example of a form. The MENA addition is highlighted.

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Federal Interagency Technical Working Group on Race and Ethnicity Standards

The revisions, currently under review, would give official recognition to a large and growing portion of the U.S. population. They would also ripple through the nation’s statistical universe and have numerous practical implications for the MENA population, especially around health care, education and political representation.

“We spent 30-plus years trying to get to the point where the census would address the massive undercount of our community,” said Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab American Institute.

Some experts worry, however, that the addition of more check boxes, along with a write-in option, might confuse respondents and make the census form too complex to generate accurate data. After all, there’s no agreed-upon set of countries or ethnicities that would fall under a Middle Eastern and North African category.

“This would be the first time since the 1970s that a completely new race or ethnicity category has been added, and that’s a very significant change,” said Margo J. Anderson, a professor emerita at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the author of “The American Census: A Social History.” “You’re asking people to answer in a much more complicated way, and MENA is just one piece of a much bigger need for testing all of these changes between now and the 2030 census.”

The Census Bureau recently announced that 3.5 million people listed a MENA origin in the 2020 decennial census, but the numbers included only those who first identified as white.

Most of what demographers know about the MENA population now comes from the Census Bureau’s annual American Community Survey, which asks respondents about race, ethnicity and also their ancestry. The most recent data, from 2022, shows that nearly four million U.S. residents — just over 1 percent of the population — listed a Middle Eastern or North African ancestry.

Those figures can also be combined with other survey questions to help demographers broadly understand the MENA population in terms of size, location and economic status, but these statistics have no legal standing. Only the categories included in the decennial census dictate how people are classified across a broad spectrum of statistical agencies.

For example, while there is robust research into the public school achievement gap between white and Black students, less is known about the performance of Middle Eastern and North African students because they are not officially tracked in federal education statistics.

When policy makers redraw political boundaries every ten years, there is often much debate over whether the new congressional districts fairly represent various minority groups. But people of MENA descent are not officially part of this conversation because they don’t exist in the data used to draw the lines.

Medical researchers can better detect elevated health risks for certain groups if they gain access to more granular race data, researchers from Cornell University recently found. During the first year of the pandemic, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was able to detect the high risk of Covid among Native Americans in large part because Native American, unlike MENA, is an official race category. Dr. Tiffany Kindratt, a health researcher at the University of Texas at Arlington who has reached a similar conclusion in her work, noted that the designation is crucial to securing funding for studies.

With so much missing information, The Times decided to conduct its own survey to learn more about those of MENA descent in the United States.

“I’m not white, I’m North African. By having to check ‘white’ — I feel like it reduces me to a certain set of expectations or experiences that don’t capture what it’s meant to be an Arab and a Muslim in America.”

Khelil Bouarrouj, 37,

identifies as North African

“I have been discriminated against and have been told to ‘go back to my country’ more times than I can count from white people. Why should I be lumped in with the very people who discriminate against me?”

Dusty Haddad, 51,

identifies as Palestinian

In the Times survey, respondents were asked several multiple choice questions about their racial and ethnic identity.

When asked to choose from a list of race options that did not include “Middle Eastern or North African,” nearly half of the 5,300 survey respondents chose “another race” and about a third picked “white.” When a MENA box was added, the change was drastic — nearly 90 percent chose either MENA alone or MENA along with one other category. (Unlike the census form, which prompts MENA individuals to identify as “white,” the Times survey did not.)

“A lot of MENA people don’t perceive themselves as being part of the majority population in the United States,” said Jeffrey S. Passel, a senior demographer at Pew Research. “Some of them perceive themselves to be subject to discrimination because of their origins.”

Nadine Naber, a professor of Arab American studies at the University of Illinois Chicago, said the lack of a MENA box made it difficult to track instances of racism and discrimination, both for law enforcement and in workplaces and universities.

At the same time, people of Middle Eastern and North African descent are often “hypervisible” and subjected to racial profiling, and stereotypes associating Muslims and Arabs with terrorism persist with pernicious consequences, Dr. Naber said. And there may be some reluctance to self-identify as Middle Eastern and North African on official forms for that very reason, she added.

“People lack access to resources and are being discriminated against, but we can’t respond because we don’t have the data,” said Dr. Naber, who is an author of a study of Arab Americans in Chicago released last year called “Beyond Erasure and Profiling.”

A small share of those surveyed did choose “white” even when a “Middle Eastern and North African” option was offered — showing how difficult it is to find universal agreement on views around identity within such a diverse population. But when MENA was an option, a much larger share of respondents chose it in addition to “white.”

Several survey respondents acknowledged the privilege that comes with the perception of appearing or presenting as “white.”

“If I look at myself, I’m not hijabi, I’m not Muslim, and I know I go around the world with white-woman privilege.”

Ceylan Swenson, 24,

identifies as white and mixed-SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African)

“In our country, race is such a loaded question that I feel like I can’t truthfully say anything other than ‘white,’ as I definitely have the privilege that goes along with that.”

Blake Bachara, 32,

identifies as white and “vaguely Arabic”

“To someone who sees me, I might present as white. But as soon as anyone hears my name, I immediately become nonwhite. I filled out ‘white’ most of the time only because I didn’t feel like I had a good option.”

Amin Younes, 35,

identifies as Palestinian and German

“We’re forced to choose between checking ‘white’ or acknowledging our identity as ‘Arab/Middle Eastern.’ But we can be both.”

Rita Obeid, 34,

identifies as Middle Eastern/Arab

The addition of a Middle Eastern and North African box would impact demographic data for all groups in the United States, and would almost certainly result in a decrease in the number of people counted as white. After all, the Census Bureau has included most MENA individuals in that category for as long as it has counted them.

The debate over how to classify people of Middle Eastern and North African descent is not new. In the early 1900s, Arab immigrants — who were mostly Levantine Christians — fought to be classified as “white” to circumvent rules that allowed only white immigrants to become U.S. citizens.

The matter became the subject of several court cases — and set in place a legal precedent that would last for decades.

The federal government issued guidelines in 1977 that defined people from the Middle East and North Africa as white. A box for this population was on the agenda when the race and ethnicity guidelines were updated in 1997, but there was not enough consensus to implement change.

Extensive research continued under then-President Barack Obama, but it did not result in any changes to the race or ethnicity categories. In 2022, the Biden administration picked it back up and asked the public to weigh in.

Thousands of people submitted feedback, which a working group is now reviewing, before final recommendations are submitted to the Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the race and ethnicity statistical standards are expected by the summer.

“The new category will allow all of us to be seen and also see each other for the first time. It’s a chance to re-emerge from the whiteness many immigrants sought to survive a century ago, but that has served to erase and harm us over the 20th and 21st centuries.”

Thomas Simsarian Dolan, 41,

identifies as MENA

“The census is the only major set of data that lawmakers and corporations and others use to see who is in this country. To not be represented in something like that, it just feels like we aren’t supposed to care about who we are.”

Gabrielle Barbara Guliana, 26,

identifies as Chaldean

The largest group of respondents to the Times survey said they were of Egyptian, Lebanese, Palestinian, Iranian or Syrian descent. Among these identities, those from Lebanon and Iran were more likely to call themselves “white.”

Respondents whose families immigrated to the United States before 1960 were also more likely to identify as “white.” For those with families arriving in more recent decades, “another race” was the most common response.

The survey also revealed differences along generational lines. While those over the age of 50 were more likely to choose “white,” respondents under 30 were less likely to do so.

“Generationally it’s a very different conversation. As you get younger, people are more likely to identify as MENA or not white, but the first generations who came to the U.S. are more likely to identify as white.”

Christina Boufarah, 21,

identifies as Middle Eastern/North African/Arab

“The wish for assimilation is very much inside every immigrant I’ve ever met — wanting to be accepted, wanting to feel safe. What’s changing is really the fact that people are refusing to put up with the shame and refusing to hide, making it easier and safer to not check the ‘white’ box today.”

Michele Magar, 69,

identifies as MENA and non-practicing Jew

“If anything, I consider myself closer in race to Black people than white people. I grew up in this city, born in 1980 and there weren’t many first-generation American Arabs in N.Y.C. My identity and race has always made me question why there are so few selections.”

Soufiane Driss, 43,

identifies as North African

Many people told The Times that they regard Middle Eastern and North African as an ethnicity, not a race. For several decades, the Census Bureau has made a distinction between the two categories. It has captured information about race for people who are white, Black, Asian or Native American. And it has inquired about Hispanic and Latino heritage as a matter of ethnicity. Under the new system, the distinction would disappear, and Middle Eastern and North African would be added to a new combined question that asks for race or ethnicity.

Some respondents took issue with the term the “Middle East,” which is generally used to refer to Arabic-speaking countries as well as others like Iran, Israel and Turkey. The term became widely used in the 1900s, when it was employed by world powers, and its borders have long been subject to debate. There is also no consensus on which countries and territories constitute the Middle East.

Particularly among younger people and academics, a different term has been adopted — SWANA, or Southwest Asia and North Africa.

It’s not an easy task to incorporate a wide swath of the world with many countries, languages, ethnicities and religions into a single box, but proponents say MENA is the most inclusive option and a good place to start.

“As an Afghan, we would get lost in the Asian box, and feel that MENA should become more inclusive like the more current term SWANA, to include Afghanistan, Turkey and Armenia.”

Azita Ghanizada,

identifies as Afghan

“The notion of being an Arab in the West is a politically charged notion — often one where you are seen as an enemy, frankly. Being in control of defining your own identity is a way of defeating the pernicious power of stereotyping.”

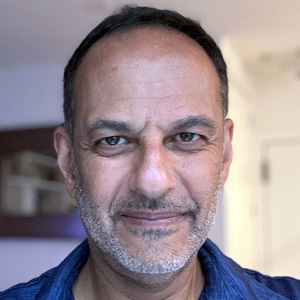

Moustafa Bayoumi, 57,

identifies as Arab American

“I can say I’m American, I’m Arab, I’m Syrian, I’m a Muslim, I’m a West Virginian. So these labels are not so simple for us to just say, ‘All you people get in this bucket.’ But if MENA is what works best for now, I’ll take whatever starts to see us or count us.”

Nawar Shora, 47,

identifies as Arab American

Methodology

The New York Times first published the survey on Sept. 29, 2022, and accepted responses through May 5, 2023. Follow-up interviews were conducted through August 2023. The Times asked more than 75 community organizations and individuals to help distribute the survey through social media and email in an effort to reach a wide cross section of the Middle Eastern and North African population in the United States.

More than 5,300 people responded to the Times survey. The responses skewed young and coastal, with a majority of respondents residing in metropolitan areas such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington, D.C. There were also responses from people from many corners of the country, from Gallup, N.M., to Macomb, Mich., to Bend, Ore.

More than a third of respondents listed their family heritage as Lebanese, Egyptian, Iranian, Palestinian or Syrian, but participants with roots in many countries across the Middle East and North Africa participated. Many said they had mixed heritage. The Times analysis included anyone who said they were of MENA descent.

Times reporters conducted follow-up interviews with more than two dozen respondents. The photos accompanying the quotes in the story were submitted by the individuals who were interviewed.

The labels accompanying colored swatches at the top of the story are a sampling of answers to this question: If you could write anything, how would you describe your race and/or ethnicity?

The bar charts represent answers to two multiple-choice questions, both of which allowed respondents to check more than one box. The first one asked: What is your race? The choices were: “white,” “Black or African American,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “American Indian or Alaska Native” or “another race.” The second question asked was: What is your race and/or ethnicity? The choices were: “white,” “Black of African American,” “Hispanic or Latino,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “Middle Eastern or North African,” “American Indian or Alaska Native” or “another race.” Charts reflect the most common responses to the survey. Values have been rounded.

In addition, The Times examined information about MENA people in the 2022 American Community Survey, including respondents who identified their ancestry among 21 distinct groups with origins in North Africa and Southwest Asia, as well as four additional ancestries (Afghan, Georgian, Sudanese, Somali) that are sometimes included in various definitions of MENA.

Read the full article Here