Pelé was the greatest soccer player — and, apparently, lover

When Pelé ended his legendary, game-changing soccer career at the Meadowlands in 1977, he went out with a special rallying cry.

Having played half the game for his final team, the New York Cosmos, and half for Santos, the Brazilian club that saw him become a superstar, Pelé said to the capacity crowd: “Love is more important than what we can take in life.”

Then he got them to chant with him: “Love, love, love.”

On and off the field, Pelé was all about sharing the love.

Last year, the icon — who passed away Thursday at age 82 — said that he had loved so many women that he had no idea how many children he had fathered.

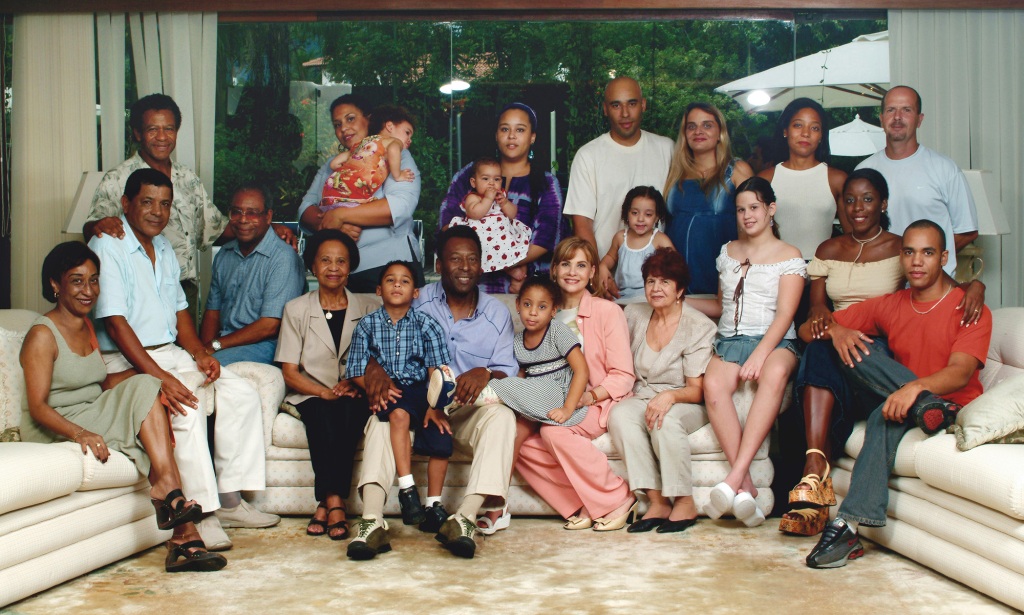

Several of the six he officially recognized gathered around their father this week at a Sao Paulo hospital and posted images to social media showing the soccer great in a hospital bed at the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo. Pelé was suffering from end stage kidney and heart problems, according to a recent report in the Brazilian press, and doctors had said he was no longer responding to treatments related to colon cancer that was discovered last year.

Also at Pelé’s bedside was his third wife Marcia Aoki, who is 26 years younger.

Known simply as “the king” of soccer for his unparalleled prowess on the field, Pelé weathered his share of scandals in his native Brazil, including dating much younger women and refusing to recognize his first child — suing her 13 times in Brazilian courts in the 1990s while he was a government minister.

Sandra Regina Machado, who was born at the height of her father’s fame in 1964, forced him to undergo a court-ordered DNA test that proved in 1996 that he was indeed her father. Machado was the daughter of Anisia Machado, a housekeeper who had an affair with Pelé before his first marriage. She died of cancer in 2006 without receiving any support from her father, according to Brazilian press reports.

Fame brought Pelé love, adoration — and heartache.

“Girls wanted Pele as their boyfriend, boys wanted Pelé as their brother, parents wanted Pelé as their son, and everyone wanted Pelé as their neighbor,” Brazilian journalist Paulo Cesar Vasconcellos said in “Pele,” a 2021 Netflix documentary. “He was totally captivating. His natural charisma gave him star quality.”

Edson Aranha do Nascimento was born on October 23, 1940, in Tres Coracoes — “Three Hearts” — a city in southeastern Brazil. Although spelled differently, his parents named him for inventor Thomas Edson to commemorate the introduction of electricity to Tres Coracoes the year he was born. He was given his nickname as a young boy once he started playing soccer.

“In Portuguese, when you kick the ball with the foot we say ‘Pe,’ and maybe I made some mistakes, I don’t know, but my teammates started to say ‘Pe-lé,’ more and more,” he later told Sky Sports. “I didn’t like it because my name was Edson, but it started and here I am. Anyway, my family and the ones [who] are close to me still call me Dico. That’s what they call me at home.”

From an early age, Pelé was a talented player. In 1950 when Brazil lost the World Cup to Uruguay on their home turf and plunged the soccer-mad country into despair, he made a promise to his father — himself a soccer player known popularly as Dondinho: “I’m going to win a World Cup for you,” Pelé recounted in the Netflix documentary.

He did just that when he was 17 years old, at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, bringing him international stardom. And then he did it again and again, leading the Brazilian national team to victories in 1962 and 1970.

In his home country, he was almost a deity. But Pelé had a hard time coping with his newfound fame. “I couldn’t go out,” he said in the Netflix doc. “It was hard to adapt.”

The athlete married his first wife, Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi in February 1966, and the couple had three children: daughters Kely and Jennifer, and son Edinho. But the marriage soon began unraveling, thanks in part to Pelé’s constant travel with his Santos team and media and advertising demands — and in part to his roving eye.

Two years after marrying Rosemeri, Pelé had an affair with Lenita Kurtz, a Brazilian sports journalist who used to cover the games for Santos, where the soccer great played for 19 seasons. Their daughter, Flavia Christina, was born in 1968.

Adding to his personal upheaval: the world’s greatest soccer player was broke.

‘I wasn’t sure about the relationship, but he insisted. He sent flowers to my mother, chatted with my dad.’

Xuxa, who began dating Pele when she was 17

In October 1974, he retired from the game after 18 years with Santos. Then his accountant broke the bad news.

“I remember the moment he entered the house as if it were yesterday. He was sweating profusely. He was pale, he looked like he was about to faint. I could tell something was wrong so I made a little joke: ‘How many million have we still got?’ ” Pelé recalled in “Pelé: A Importância do Futebol,” his 2013 biography. “I nearly had to call the doctor when he replied: ‘Look, this is very difficult . . .’ ”

Pelé was on the verge of bankruptcy and lost almost all of his 41 investment properties to bank seizures, following a cascade of poor advice and building debt.

A succession of bad business deals and equally poor legal advice had left Pele with substantial debts in Brazil with one of his investments in Fiolax, a company that made rubber components for the car industry, which proved to be his biggest headache.

While his stake in the company stood at just 6%, he had personally guaranteed a loan the company had taken out and when Fiolax defaulted, the bank had come looking for him. Coupled with a fine related to corporate regulations, Pele was now looking at a bill of more than $1 million.

His financial salvation came in the form of the New York Cosmos, a short-lived professional soccer club, and a contact that would make him the highest paid athlete in the world.

Cosmos General Manager Clive Toye had tried on several occasions to sign Pelé for the team, holding meetings in Sao Paolo, Frankfurt and London. Now was Toye’s chance.

The Englishman flew to Brussels, where Pelé was due to play in a charity game and had just one hour before he was scheduled to fly out to Casablanca for an audience with the King of Morocco. Despite interest from some of Europe’s biggest soccer clubs, like Juventus in Italy and Real Madrid in Spain, Toye’s sales pitch was completely different: “I said if you go there, all you can do is win another championship. If you come here, you can win a country.”

Warner Communications, the owners of the Cosmos, wanted to own Pelé lock, stock and barrel and prepared a succession of contracts. There was a 10-year deal for his marketing rights and a 14-year PR deal to represent Warner. There was even an agreement for him to be a recording artist for Warner’s Atlantic Records label. He was given two homes, an office suite at Rockefeller Plaza and guaranteed spots in NYC’s best schools for his kids.

The total deal would be worth a reported $4.7 million over three years.

Eight months after he retired, Pelé was on the pitch in America.

Rosemeri and the kids, who lived in a small Manhattan apartment before eventually settling in Queens, came with him. But with Pelé traveling back and forth between Brazil and the US, participating in lucrative advertising campaigns, the couple separated in 1978.

They didn’t divorce until 1982, a year after Pelé’s affair with Xuxa Meneghel, a children’s entertainer, became public. Leggy blonde Xuxa — who, like Pelé. is known by one name in Brazil — was 17 years old to the soccer star’s 41.

“My heart was beating very strongly,” Xuxa told a Brazilian podcast last year in which she admitted that Pelé was her first love. “I said: ‘Why am I doing this with a guy who is a lot older than I am?’ I wasn’t sure about the relationship, but he insisted. He sent flowers to my mother, chatted with my dad. I was with him from 17 to 23. It was six years. Pelé really had a double personality. He speaks of himself in the third person, but I was truly in love with him. He was very close to my family and he was a lot of fun.”

The relationship helped the young entertainer reach dizzying heights of stardom in Brazil.

Following his affair with Xuxa and his divorce from Rosemeri, Pelé had a relationship with Selma Fonseca, a writer for Billboard whom he met in 1989 when she was 23 and he was nearly 50.

“We [met] in NYC . . . After a long courtship we dated for nine months,” said Fonseca in an interview on Medium last year. “He wanted to get married but, because of various circumstances, we didn’t. But he was loving, fun, a gentleman, always very grateful for his success and generous. He was happy to sign autographs, take photos and hug his fans, it was awesome to see how he took the time for everyone.”

A few years after that relationship, Pelé married gospel singer Assiria Seixas Lemos in 1994. The couple’s twins, Celeste and Joshua, were born two years later.

In 1995, Pelé was named Extraordinary Minister for Sports in Brazil and faced increasing pressure from his first child, Machado, to submit to a DNA test. She eventually adopted his surname, wrote a book — “The Daughter the King Didn’t Want” in 1998 — and used her notoriety to run for city council in the city of Santos, where Pelé’s old team was located. As a politician, Machado lobbied for free DNA tests to be provided to children searching for biological parents, a practice that continues to this day.

In 2001, Machado filed suit demanding compensation from the soccer great, claiming in court papers that she did not enjoy the same emotional and financial support as his other children. The court rejected her claim.

Pelé, who did not show up for Machado’s funeral in 2006, later told a Brazilian reporter that he had decided not to pursue a relationship with Machado because people close to her had approached him “in a not very friendly manner.”

He later relented when approached by Machado’s ex-husband, Ozeas Fellinto, who took the Machado’s two children to meet Pelé.

“I just want to say that Sandra never received anything from Edson Arantes, not even a glass of water,” Fellinto said in a press statement. “While Sandra was alive, her mother, who worked as a housekeeper, raised her. Pele never helped.”

Fellinto later said that Pelé was paying for the children’s education after being taken to court.

Follwing a divorce from Lemos in 2008, Pelé married his third and final wife, Marcia Cibele Aoki in 2016. The couple had met at a New York party in the 1980s, when Aoki was still a teenager, and then again in 2008. A Brazilian of Japanese origin who owns a medical supplies company, Aoki has no children with the soccer legend.

The athlete described her in an interview as “the last great passion of my life.”

But as he watched Brazil lose to Croatia in the World Cup from his hospital room earlier this month, it was clear what was still Pelé’s greatest passion. He told his 13.3 million Instagram followers: “To all Brazilians, I wish you the union and the love that binds us in sport binds us throughout our lives. The dream is of all of us. Love, love and love.”

Additional reporting by Gavin Newsham

Read the full article Here