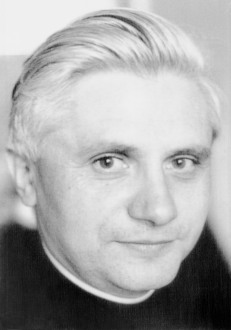

Pope Benedict XVI dead at 95

Pope Benedict XVI, a fierce defender of church dogma who became the first pontiff in six centuries to abdicate the papacy, died Saturday morning. He was 95 years old.

“With sorrow I inform you that the Pope Emeritus, Benedict XVI, passed away today at 9:34 AM in the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in the Vatican,” the Holy See Press Office announced.

Benedict XVI’s body will lie in state at Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City beginning on Jan. 2, according to the Vatican.

His death came after Pope Francis asked his flock for “prayers” for his predecessor at the Vatican Wednesday.

“I want to ask you all for a special prayer for Pope Emeritus Benedict who sustains the Church in his silence. He is very sick,” Francis, 86 said during his weekly general audience.

“We ask the Lord to console and sustain him in this witness of love for the Church to the very end.”

The German-born spiritual leader — born Joseph Ratzinger on 16 April 1927 in Bavaria — succeeded the sainted Pope John Paul II in 2005.

Known for his staunchly conservative views and the nearly 25 years he spent as the powerful head of the Vatican’s doctrinal office, Benedict became the first German pope in 1,000 years — but only served for eight years before deciding to step down in 2013.

“I think that if he had been able to decide his own future, he would have been quite happy to spend his life as a college professor, teaching and writing books,” the New York Archbishop Timothy Cardinal Dolan told The Post in December 2018.

“But he was called to greater service… And he accepted all of this as one who follows not his own will, but God’s will.”

As a quiet, unassuming intellectual who mostly stayed out of the limelight, Benedict didn’t often comment on political issues, but will be remembered for his extensive writings and teachings about the love of God and the love of one’s neighbor.

Benedict produced more than 60 books between 1963, when he was a priest, and 2013, when he resigned.

However, his short tenure was marred by the clergy sex abuse crisis, which reached a peak in the public sphere during this time, and the “Vati-leaks” scandal.

Paolo Gabriele, Benedict’s butler, leaked secret documents to an Italian journalist in 2012 that revealed corruption and feuding within the Vatican.

The stolen documents uncovered power struggles inside the Vatican over its efforts to show greater financial transparency and comply with international norms to fight money laundering.

After Gabriele was arrested, he admitted that he’d given the papers to reporter Gianluigi Nuzzi because he believed the pope wasn’t being informed of the “evil and corruption” in the Vatican.

He insisted that he believed exposing it would get the church back on track.

A year after the scandal rocked the Holy See, Benedict, at the age of 85, stepped down.

However, he said he had to step aside because his health prevented him from being of sound enough mind and body to lead the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics.

“In today’s world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith, in order to govern the bark of St. Peter and proclaim the gospel, both strength of mind and body are necessary, “ he said.

“Strength which in the last few months has deteriorated in me to the extent that I have had to recognize my incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry entrusted to me.”

Everyone, even the Vatican’s own spokesman, was taken aback by the announcement: the head of the church was quitting — the first since Pope Gregory XII in 1415.

Years later, Benedict’s stunning decision was lauded by church leaders and experts as courageous and a sign of true humanity — to be able to recolonize one’s own failings.

“It was really a moment of humility. He admitted his own weakness and kind of demystified the papacy,” Christopher P. Vogt, the chair of the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at St. John’s University told The Post in Dec. 2018.

“He didn’t try to hide behind the mystic of the papacy. He was clearly a man of faith dedicated to serving the church the best way he could.”

Following Benedict’s shock resignation the pope emeritus spent the last years of his life in near seclusion at a Vatican City monastery, blind in his left eye and unable to walk unattended.

Benedict had also endured other health setbacks in his life. In 1991, he’s suffered a hemorrhagic stroke and then suffered another stroke in 2005. He was also fitted with a pacemaker as a Cardinal, though this was only revealed following his resignation.

A church insider told The Post Benedict largely spent his days reading, praying, doing a little writing and occasionally meeting with old friends.

He was succeeded by a charismatic Argentinian Cardinal who became Pope Francis.

At the time of Benedict’s election, he’d been a natural choice within the college of 115 cardinals who chose him, as the man who shared his predecessor John Paul II’s traditionalist ideology, having served as his right-hand man for two decades.

When he donned his robes on April 19, 2005, at the age of 78, he became the eldest pontiff to be elected since 1730.

Born on Holy Saturday, April, 16, 1927 in the committed Catholic German village of Traunstein to a policeman father and hotel cook mother, Benedict was 6 when Adolf Hitler came to power.

He was a 12-year-old student about to enter a seminary when Germany invaded Poland, igniting World War II.

In 1941, Benedict was pressed into the compulsory Hitler Youth movement, a fact that caused widespread criticism upon his ascension to the papacy — though the future pontiff was “not an enthusiastic” member, wrote his biographer John Allen.

Later, Benedict recalled in his memoirs that during this troublesome time the church was “a citadel of truth and righteousness against the realm of atheism and deceit” — a feeling that influenced his choice to join the priesthood.

Both he and his brother Georg, also a priest, joined the German army and Benedict underwent basic infantry training in late 1944. He deserted when the country began to be invaded by Allied forces and ended up in an American POW camp for several weeks.

After the war, he returned home and to the seminary, having been convinced that God “wanted something from me, something which could only be accomplished by becoming a priest.” He was ordained in 1951.

Soon, Benedict became known as one of the intellectual stars of the West German church and traveled to Rome in 1962 to serve as one of the young aides to Joseph Cardinal Frings of Cologne.

During his time in the Vatican, he was known as the official responsible for reigning in dissident priests — and even earned the nickname “God’s Rottweiler” — and he began to have second thoughts about the direction the church was taking.

“I found the mood in the church and among theologians to be agitated,” he wrote. “More and more there was the impression that nothing stood fast in the church, that everything was up for revision.”

For Benedict — who became associated with the conservative wing of the church, known for its fierce opposition to moral “relativism” on issues such as homosexuality, contraception and women priests — some things weren’t up for debate.

The world was changing and student protests of the late 1960s were reverberating from Manhattan to Paris to the University of Tuebingen, where Benedict had a teaching post.

“He had big clashes with his most intimate students and assistants,” Rev. Hans Kung recalled to The Post in 2005.

A short time later, a deeply distraught Benedict moved to the more conservative University of Regensburg.

“I had the feeling that to be faithful to my faith I must also be in opposition to interpretations of the faith that are not interpretations but oppositions,” he later said.

Benedict’s warning about the danger of abandoning traditional church views became familiar in Germany — and took on greater authority when he moved to Rome and his star began to rise.

Benedict was appointed bishop of Munich in 1977 and elevated to cardinal three months later by Pope Paul VI.

“On the one hand he is a conservative figure, supportive of traditional family and marriage, sexual mores,” Vogt said. “But at the same time he’s very progressive, he believes in the rights of labor, the rights of the poor, having a right to food.”

In Italy, Benedict struck up what would become a 40-year friendship with the archbishop of Krakow, Karol Cardinal Wojtyla — who was elected John Paul II in 1978.

John Paul named him to head the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1981 as guardian of church dogma, which he served in for nearly 25 years.

In that role, he was also charged with investigating and policies surrounding sexual abuse.

In that role, he led important changes to church law, such as the inclusion of crimes against children related to the Internet and a case-by-case basis for waving the statute of limitations.

He then became the first Pope to kick predator priests out of the church — following a series of embarrassing scandals in the US, Ireland and Australia.

In 2011 and 2012, the last two full years of his papacy, 384 abusive priests were defrocked — though this action only took place after the anus horriblis of 2010 that saw numerous sexual abuse cases pop up almost weekly.

As pope emeritus, Benedict didn’t comment on his successors’ policies or any other scandals that arose, largely keeping to himself.

“He has successfully moved out of the spotlight and not tried to align himself with critics of Francis,” Vogt said. “He sees this as a time of prayer and reflection.”

A report commissioned by a German archdioceses released in early 2020 found the former pontiff mishandled four abuse cases when he served as archbishop in the 1970s and 1980s. Benedict denied wrong doing.

It’s still unclear how Benedict’s shock resignation will affect the future of the church — but it was no doubt significant.

“It has shifted the understanding of what it means to be in that position, that it is something you can potentially leave,” Vogt said.

Cardinal Dolan believes the effect has been a “positive one.”

“The effect on the Church has been, I think, a positive one, in that it was such a display of humility; it’s been a reminder to me that I should not be too attached to the things of this world,” he said.

Dolan, who was appointed Archbishop of New York in 2009 by Benedict described him as a “man of great faith, humble, warm, gentle, soft spoken.”

He was “someone who listened carefully, and was then able to quickly and accurately summarize and synthesize the various points of view expressed.”

“His legacy will almost certainly be as one of, if not the, pre-eminent theologians of the 20th and 21st Centuries,” Dolan said.

Read the full article Here