Real women inspire Taylor Sheridan’s ‘Special Ops: Lioness’

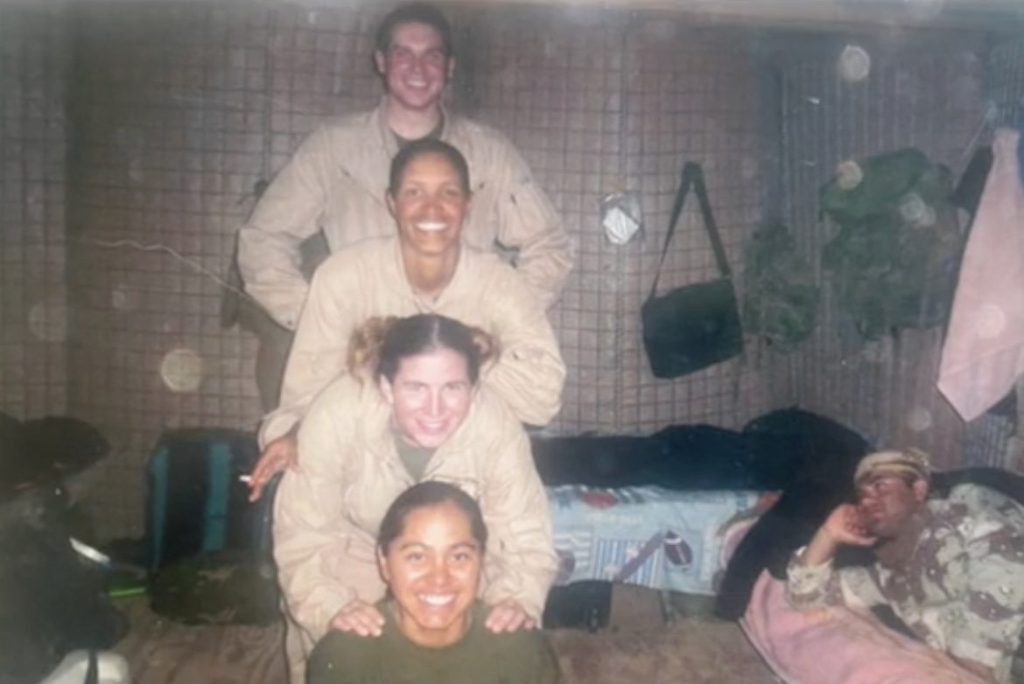

To ring in her 21st birthday on February 18, 2007, Amy Folwell gripped a can of Bud Light in one hand and her military-issued rifle in the other.

“My [gunnery sergeant] gave me the beer and said, ‘If you die in service, at least you’ve had your first legal drink,’” Folwell, now 37, a medically-retired lance corporal of the United States Marine Corps, told The Post.

“It was pretty exciting,” she added.

The Rochester, New York, native’s personal milestone coincided with her first day of deployment to Ar-Rutbah, Iraq, where she served as a “Lioness” with Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, for three months.

As a Lioness — a team of intrepid female service members quietly established by the Marines in 2003 — Folwell was one of the three female troopers to be attached to a combat unit.

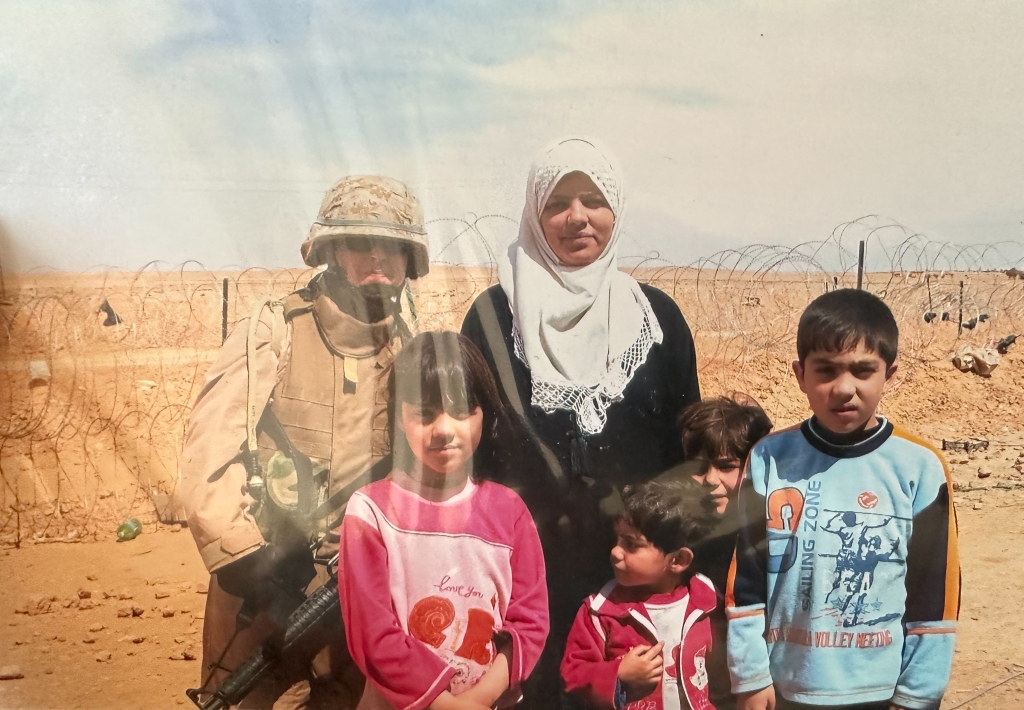

Stationed at the gates of the Korean Village territory, she was tapped to search Iraqi women and children for arms and bombs.

The trailblazing Lionesses served as the inspiration for Paramount’s forthcoming action thriller “Special Ops: Lioness,” which debuts Sunday and stars Zoe Saldaña, 45, alongside Oscar winners Nicole Kidman, 56, and Morgan Freeman, 86.

The eight-part series — a brainchild of Taylor Sheridan, the visionary behind “Yellowstone” — follows the journey of a young Marine named Cruz Manuelos (Laysla De Oliveira, 31, of Netflix’s “Locke & Key”).

She’s recruited by the CIA’s Lioness Engagement Team to befriend the daughter of a terrorist leader in an effort to penetrate the criminal organization.

Saldaña, who plays Joe, the station chief charged with readying new recruits for undercover operations, explains the significance of the niche program to De Oliveira’s Cruz in the first episode, noting the evolution of their task force’s duties over the past two decades.

“When the Lioness team was first formed, we needed female soldiers to frisk and interrogate female insurgents,” she says.

“What we do now is locate the wives and the girlfriends and daughters of these high-value targets and we place an operative close to them,” continues Joe. “The operative makes friends with them, earns their trust, leads us to the target and we kill the target.”

Folwell’s responsibilities didn’t center around covert espionage, but says serving as a Lioness was “life changing” — for both good and bad.

“We made sure that everyone was safe and no one was carrying any weapons of mass destruction or [improvised explosive devices] or anything that could cause damage throughout the village,” she told The Post. “We conducted humanitarian aid missions and went to refugee camps where we supplied water and food.”

“It was very exciting and incredibly humbling.”

Folwell’s was a groundbreaking post.

In October 1994, nearly a decade before the Lioness program was launched, servicewomen were banned from ground combat due to the risks.

However, in the early 2000s, with the U.S. military deployed throughout the Middle East after 9/11, women warriors were needed to engage with female civilians in ways servicemen couldn’t without causing cultural and religious offense. (The ban on women in combat was officially lifted in 2013.)

In the 2015 book “Ashley’s War: The Untold Story of a Team of Women Soldiers on the Special Ops Battlefield,” author Gayle Tzemach Lemmon tells the story of 1st Lieutenant Ashley White-Stumpf, who ferociously fought with the U.S. Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment in Afghanistan in late 2011. White-Stumpf was killed by an IED on Oct. 22 that year — she was one of three soldiers to die in the explosion.

“Make no mistake about it, these women are warriors,” said retired Lt. Gen. John Mulholland, former head of Army Special Operations Command, per Lemmon. “They absolutely will write a new chapter in the role of women soldiers in the United States Army and our military, and every single one of them have proven equal to the test.”

And Folwell is proud to count herself among them.

She spontaneously enlisted in the military at age 20, helped by a recruiter she spotted at a local mall.

At the time she was a Monroe Community College undergrad, juggling two part-time jobs in attempt to make ends meet while pursuing a degree in political science. Despite her heavy workload, Folwell felt her life was “going nowhere fast,” and wanted to contribute to society in a more meaningful way — the honorable way that her oldest brother, an Army veteran, and grandfather, a retired serviceman, had done.

And she says every day as a Lioness in Iraq made her grateful for the privileges she enjoyed living in the US.

“It was life-changing to go from being in our great nation, where everything is basically handed to you,” she said, “then going over there and seeing the difference between how we live and how [Iraqis] live. They’re in handmade huts, but they’re so happy.”

Although Folwell’s experience overseas was mostly positive, it wasn’t without damage.

“I sustained a traumatic brain injury after being hit by an IED during a convoy,” she said. Following the attack, she retired. Folwell returned to the US on September 11, 2007, and is now a mother of two and a social worker.

And while she still suffers from PTSD, migraines, anxiety and sleep issues incurred during her service, she refuses to let these impediments define her.

“I’m just thankful to be alive. Not everyone over there was so fortunate,” Folwell said, noting that another female soldier had been killed in a suicide bombing at her forward operating base, just a month before she arrived in the war zone.

She’s thankful, too, that the Lioness team, and servicewomen as a whole, are getting the recognition that they deserve.

“Women are needed in duty much more then they’re given credit for,” said Folwell. “It should be known that there are women in combat doing great things.”

Read the full article Here