Retail king Crazy Eddie Antar led an even crazier real life

If you lived in New York during the ’70s and ‘80s, the “Crazy Eddie” commercials were as ubiquitous as they were annoying.

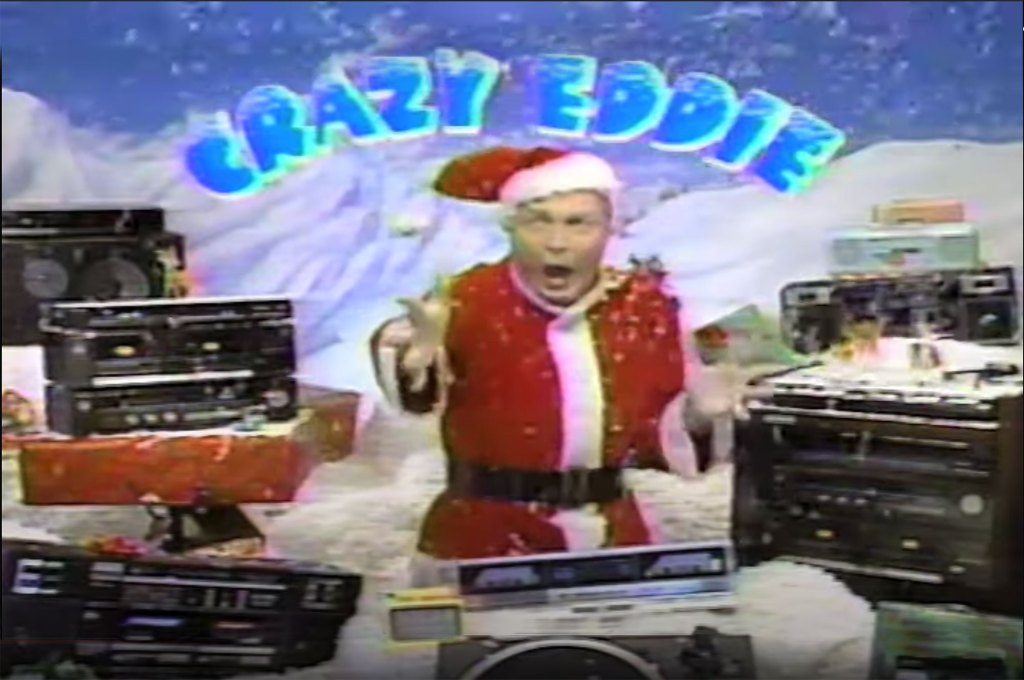

Plugging a chain of discount electronics stores by the same name, the spots featured local disc jockey Jerry Carroll — who played the titular role of Eddie — wildly pitching his wares with maniacal energy, arms waving and his voice about to burst. Each ad ended with Carroll shouting at the screen, “Crazy Eddie, his prices are in-s-a-a-a-ne!”

Those memorable commercials, more than the insane prices, “brought customers through the doors and helped the chain become a power in Northeast retailing,” writes Gary Weiss in his new book, “Retail Gangster: The Insane, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie” (Hachette), out now.

The real Eddie was Eddie Antar, a Brooklyn-born businessman who ostensibly got his “crazy” nickname from customers. “I wouldn’t let a person walk out the door without selling,” he once told a reporter. In 1969, he opened Sights and Sounds, his first discount electronics store — selling stereos, records, VCRs, clock radios and television sets — in Brooklyn. But thanks to the TV and radio commercials, which started airing in 1976, the company — renamed Crazy Eddie’s —expanded to more than 40 locations across the northeastern US, including Boston and Philadelphia.

The commercials’ appeal, ironically, was their abrasiveness. Customers vented in survey cards, complaining that the spots were so horrible that they’d “never go to your stores.” Antar saw this as proof that his marketing worked — after all, the survey cards were only available in the store.

“People might get irritated by them, but they remember,” says Larry Weiss (no relation to the author), Crazy Eddie’s advertising director for almost a decade — he wrote and produced over 3,500 Crazy Eddie TV and radio spots.

Crazy Eddie didn’t just attract customers; it became a cultural phenomenon. The commercials were parodied on “Saturday Night Live,” featured in movies like “Splash” and became “as much a symbol of the city as the Brooklyn Bridge and the World Trade Center,” writes Weiss. “In 1985, a survey found that the Carroll character was better known to New Yorkers than the publicity hound Mayor Ed Koch. A year later, the stores had 99 percent name recognition, higher than Ronald Reagan. A popular brand of smack was called ‘Crazy Eddie.’”

When Antar started opening new stores in the late ‘70s — first in New Jersey and Westchester, soon after in Long Island and on East 57th Street in Manhattan — crowds showed up like it was a major event. Twenty thousand people stood in line for the East Brunswick store opening in November 1978, for free T-shirts and Frisbees and a chance to meet Jerry Carroll in the flesh.

“These store openings were extraordinary,” says Harry Spero, who joined the advertising team at the end of 1979. “We would promote the hell out of them, and there would be lines ’round the block for people to get a free T-shirt.”

Growing up, Antar didn’t seem poised to be one of the most successful discount retailers in New York history. The grandson of Syrian Jewish immigrants, he dropped out of Brooklyn’s Abraham Lincoln HS at 16, with no real talents other than “ripping off customers at tourist traps in Midtown Manhattan,” writes Weiss, selling them products like binoculars at exorbitant markups.

His first retail operation, which he co-owned with his father, Sam, and cousin Ronnie, didn’t have an especially bright future. Fair trade laws required every business, large or small, to use a standard retail price for all electronics. An independently-owned store like Sights and Sounds was at a “significant disadvantage against major chains,” writes Weiss. Prices were enforced “as rigidly as the party line in Moscow.”

So Antar found ways around the laws, skipping the official manufacturers and instead buying his products from places like Corner Distributors, a retail operation in the North Bronx with a shady reputation. “Corner was one of the businesses in New York City of the 1970s with which you did not f–k,” writes Weiss. He bought from them (and overseas vendors) at prices slightly above wholesales. He, in turn, could offer steep discounts to customers because his overhead was lower than his competitors.

When Antar decided to buy commercial time, it was an unprecedented move at a time when consumer electronics was rarely (if ever) advertised on TV. Larry Weiss came up with the original concept, which ended with the line, “Crazy Eddie, the man is insane!” Antar “freaked out” when he first heard it, remembers Weiss. “‘What are you talking about? I am not!’ Somehow he took it personally.” So Weiss suggested a compromise, altering the tag line to “Crazy Eddie, his prices are insane.”

Despite his aversion to being called crazy, Antar did have some quirks that lived up to his media identity. As Weiss remembers, Antar had an old, torn sweater that he considered a good luck charm, which he wore almost constantly for two years straight.

In February of 1977, Antar, who had a drinking problem, got into a fight outside a club and was stabbed in the abdomen. He survived, but it was a potential public relations nightmare.

“Crazy Eddie was supposed to be a fun store, a place you could bring the kids,” writes Weiss. “Crazy but in a nice way, not in a ‘founder gets stabbed’ way.” Because Antar avoided the limelight, he wasn’t recognized and the story never made the limelight.

He made questionable investments — he spent millions on a Caribbean medical school that “was in the process of defaulting on every debt it owed,” Weiss writes, and shut down within months because of a federal lawsuit — and stole every chance he could, including the Crazy Eddie logo used on everything from print ads to t-shirts, which was lifted (without compensation) from a Zap Comix cover by cartoonist R. Crumb. (“I was sort of flattered,” Crumb said about the stolen image years later.)

Antar’s dad, Sam, wasn’t pleased that his son and co-owner of the chain “had surpassed him, outshined him,” Weiss writes. So he hatched a plot to oust his son. He knew that Antar was cheating on his wife, Debbie, with a woman also named Debbie. (To avoid confusion, he called his mistress “Debbie II.”) If the couple divorced, Sam reasoned, they could fire Antar to protect his one-third stake in the company, to keep it from falling into Debbie I’s hands.

When Debbie I learned that her husband would be spending New Year’s Eve, 1984, with Debbie II and not investors, as he’d told her, Sam encouraged her to confront him. So she and Antar’s sister drove to Manhattan and found him in a limo parked on East 80th Street, waiting for his mistress.

“A screaming match began involving all three women, with Eddie bringing the confrontation to a boiling point by slapping his sister across the face,” writes Weiss. The police were called, but Antar escaped in his limo before arrests could be made. The scuffle became known in the family as the “New Year’s Eve Massacre.”

Antar did get a divorce shortly after, but Sam’s scheme didn’t work. Antar avoided a financial disaster by tricking Debbie I into signing divorce papers without reading them, using the same aggressive sales techniques he used with customers.

The fine print left her not with a 50% split, as he’d promised, but a “big hot slice of bupkis,” Weiss writes.

Crazy Eddie commercials weren’t just unavoidable in the late ’70s. They were cool — or “pop cult,” as The Village Voice declared in 1977. “The Antar family enterprise was getting the kind of buzz usually reserved for the latest girl bands, Andy Warhol, and films by Cassavetes, Godard and Scorsese,” Weiss writes.

The spots were so huge that Antar launched his own production studio called Crazy Ads, whose clients included 2001 Odyssey, the disco made famous in “Saturday Night Fever.” Even James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, wanted to be a part of the action, calling Larry Weiss personally and asking “to be the TV spokesman for Crazy Eddie,” he says. (These were, the author points out, “times of declining record sales and Internal Revenue Service troubles for the performer. Even legends need to eat.”)

But Crazy Eddie’s success was more smoke and mirrors than a legitimate business. He managed to make huge profits — $350 million in annual revenues by the mid-80s —despite offering steeply discounted products because he pushed for customers to pay in cash and would pocket the sales tax.

He also profited from insurance scams. If any of his stores had water damage from leaking roofs or pipes that froze and burst during the winter, he had his employees collect any merchandise that wasn’t selling and move them into the flooded store.

“Eddie was sure to run up a hose to maximize the water flow,” Weiss writes. “He sometimes had the guys dump gear out of boxes and put the contents in sinks filled with dirty water.”

But the fraud that would ultimately lead to the company’s downfall involved an even more elaborate deception. In September of 1984, Antar took the company public, and investors snatched up nearly 2 million shares of Crazy Eddie for $8 apiece, under the ticker CRZY. The stock climbed 25% in just a year, driven by record profits.

But the company’s growth was another con. By reducing how much they skimmed from sales — the off-the-books cash flow that Antar hid under his floorboards and in mattresses — it created the false impression that profits were skyrocketing. “Between 1982 and 1983, real-world profits climbed 9 percent,” Weiss writes. “Cutting back on the skim bloated that number way up to a fabulous 35 percent.”

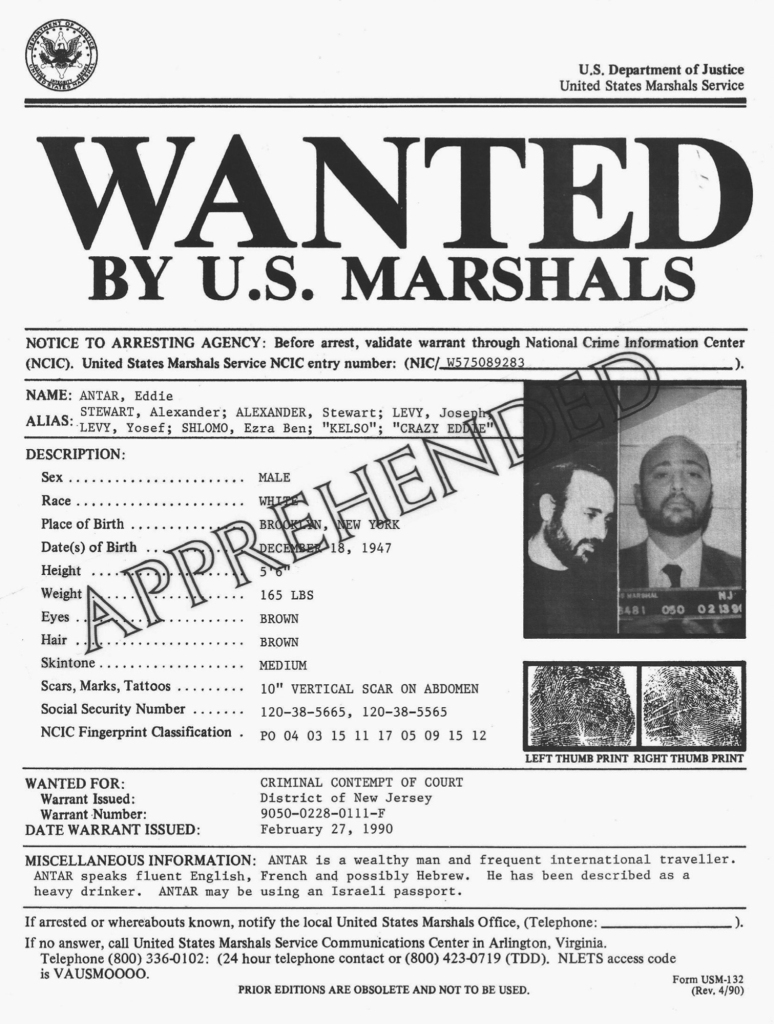

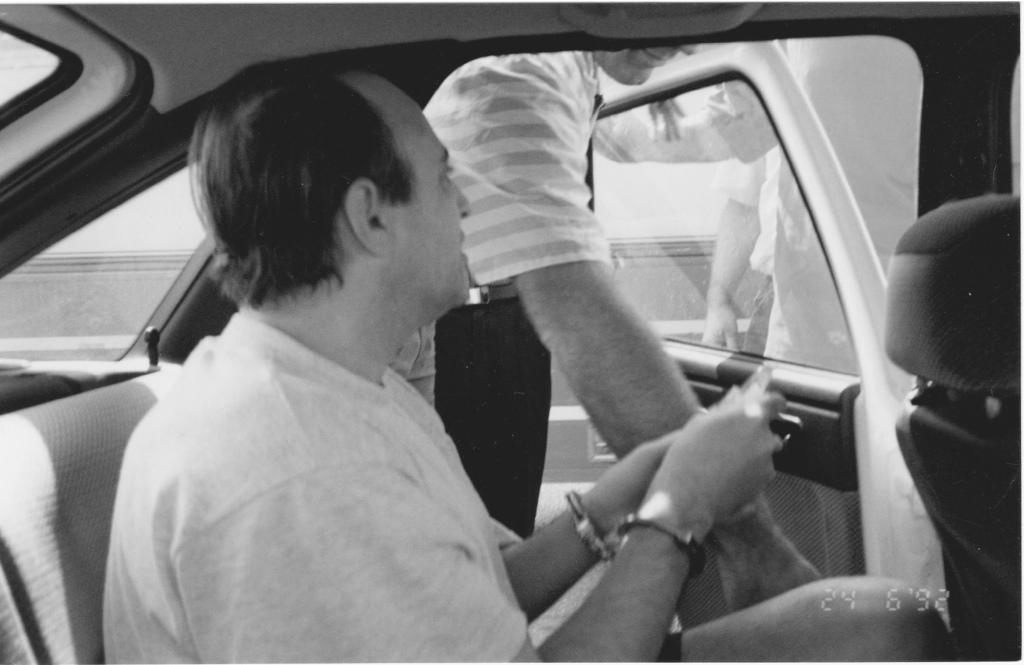

The house of cards began to fall in 1987, when a hostile takeover bid by stockholders uncovered massive fraud, including stock manipulation and over $45 million in inventory that did not exist. The Crazy Eddie chain filed for bankruptcy protection in 1989, and Antar fled the country with six passports (in five different names), around $43 million in cash, and Debbie II. He stayed on the run for three years, zigzagging between Tel Aviv, Zurich, São Paulo, and the Cayman Islands, before finally getting arrested in 1992 and extradited back to the US.

He pleaded guilty to federal fraud charges — the prosecutor in his case called Antar “The Darth Vader of Retail” — and was sentenced to eight years in prison and more than $150 million in fines.

Just weeks after sentencing, the man who rarely gave interviews spoke to The Post, insisting that he “was not involved in any fraud.” He’d left “a healthy company, a cash machine,” Antar asserted, but it was brought to “bankruptcy level” by new management.

He was released from prison in 1999 into a world where the Internet was “draining the life out of consumer electronics chains,” writes Weiss. Antar tried launching an online version of Crazy Eddie’s, predicting that it would “rise to the top.” But investors “didn’t want to go anywhere near Eddie,” writes Weiss, and the website was taken down by 2004.

“People might get irritated by them — but they remember.”

Crazy Eddie’s advertising director on the mad TV sales pitches

When he died at age 68 in September of 2016, not even his family knew for certain what happened. “Cirrhosis of the liver by one account, liver cancer by another,” writes Weiss. “His drinking had caught up with him, or perhaps not.”

News of his passing led to an outpouring of nostalgia. “I’m wistful for Crazy Eddie,” a New Yorker writer mused. “Back then, at least, chain stores were weird.” He represented “a screaming ghost of the past,” writes Weiss, “emblematic of a vanished working-class New York… a lethal, exciting city that was deeply, exuberantly crooked.” A criminal like Bernie Madoff was the nightmare you try to forget, but Antar was “the fever dream you try to remember even though it was strange and scary and made no sense.”

Read the full article Here