Socialite Unity Valkyrie Mitford was ‘Hitler’s girl’

British socialite Unity Valkyrie Mitford had one goal in life: to meet Adolf Hitler.

In 1934, the 19-year-old delinquent debutante set off to Munich. She learned German and went to the fuhrer’s favorite restaurant every day, waiting for him, sometimes for hours and hours.

He eventually noticed. The day he invited her to sit at his table — Feb. 9, 1935 — she could have died from happiness, she said. “When one sits beside him it’s like sitting beside the sun,” Unity wrote her father, the Right Honourable Lord Redesdale. “He gives out rays or something.”

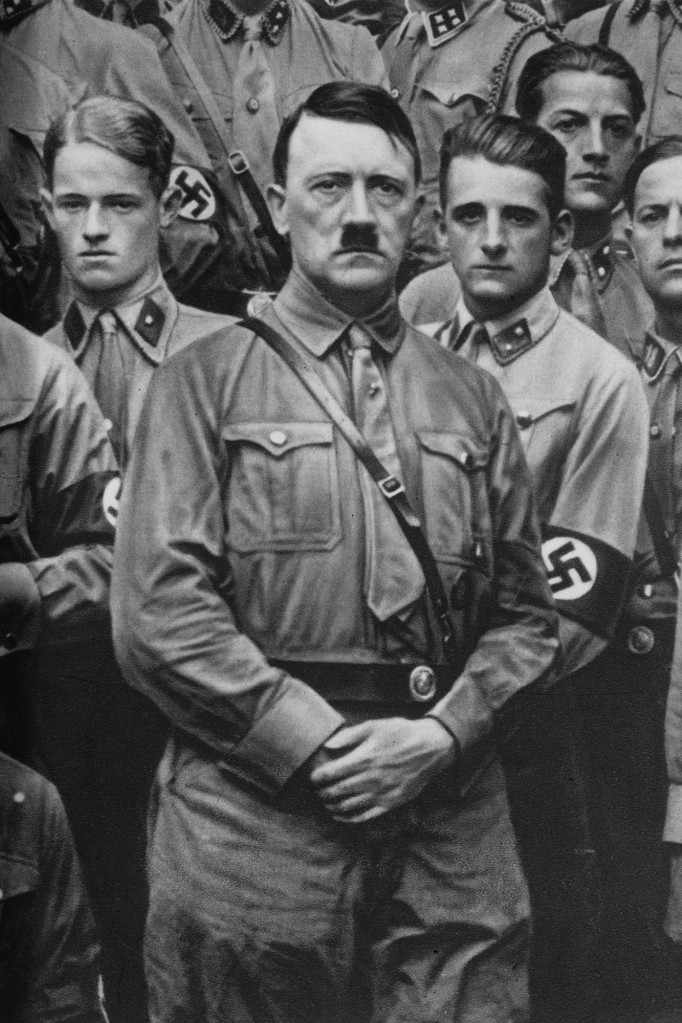

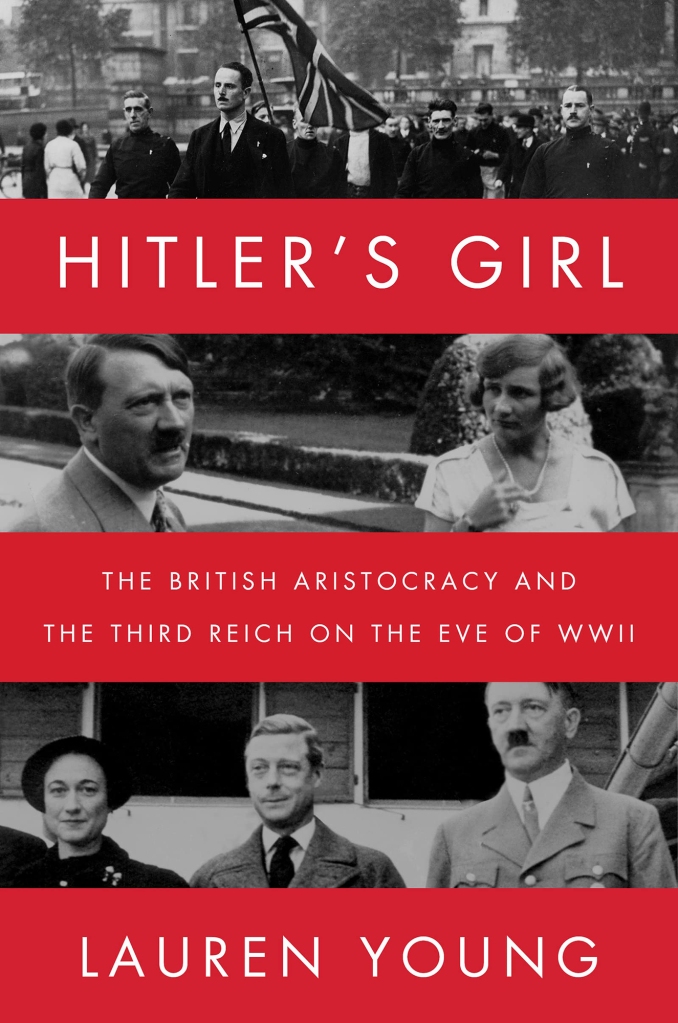

Unity — one of the famed six Mitford sisters — wasn’t the only upper-class Brit in thrall to Hitler, according to Lauren Young’s new book, “Hitler’s Girl: The British Aristocracy and the Third Reich on the Eve of WWII.” (Harper). Young, a defense analyst and Yale professor, reveals a whole network of elites who methodically pushed a pro-Germany, pro-fascist agenda in England. (She even makes the case that it was the Nazi sympathies of Prince Edward and paramour Wallis Simpson — and not Simpson’s status as a divorcée — which forced his abdication.)

But Unity was different. The statuesque “Nordic beauty” actually befriended Hitler. In five years, they met more than 160 times. She traveled with him, introduced him to most of her family and spoke at his rallies. The British press dubbed her “Hitler’s girl,” and London society gossiped that the two would marry. Hitler’s long-time mistress, Eva Braun, was so jealous she tried to kill herself.

Then in September 1939, England declared war on Germany. Four months later, Unity arrived on British shores, having shot herself in the head. She hadn’t died, but the bullet had lodged in her brain. She exited the boat on a stretcher, a blanket wrapped around her, escorted by her mother and youngest sister. M15 agents and police stood by, but the government told them to hold off on questioning her.

They never got around to it.

Unity Valkyrie Mitford was born in 1914 in London, the fifth child of David and Sydney Freeman-Mitford. Incredibly, they conceived her in Swastika, Ontario, where the cash-strapped aristocrats went prospecting for gold. Eventually, David inherited the title of Lord Redesdale and moved the seven kids to a manor house in bucolic Oxfordshire.

Unity and her sisters — the lone brother got to attend boarding schools — grew up in “eccentric and relatively unbridled isolation,” writes Young. “Raised by nannies, largely ignored by their parents and speaking a secret language called Boudeledidge.”

Even among the idiosyncratic Mitfords, the 6-foot-1 Unity stood out. As a debutante, she “shone like an enormous peacock in flashing sham jewels” and stole stationery from Buckingham Palace, wrote her younger sister Jessica in her memoir “Hons and Rebels.” She attended balls with her pet snake, Enid, around her neck and let loose her rat, Ratular, when things got boring, which they invariably did.

“She was generally out to shock — to ‘épater les bourgeois,’ as my mother disapprovingly put it — and in this she succeeded,” Jessica wrote.

Finding debutante life dull as dishwater, Unity accompanied her big sister Diana to a meeting with the British Union of Fascists; Diana, married and a mother of two, was having an affair with its leader, Oswald Mosley. The “blackshirts,” with their violent rhetoric, thuggish posturing and severe uniforms, proved much more her speed. “It’s such fun!” Unity told Jessica, pressing her to join too. (She became a communist instead.)

In 1933, the BUF asked Unity and Diana to travel to Germany to attend a Nazi rally. That’s when Unity fell in love with Hitler.

’When one sits beside him it’s like sitting beside the sun. He just gives out rays.’

Smitten-for-Hitler socialite Unity Valkyrie Mitford

“He looked so touching,” she wrote to her family. “The first time I saw him I knew there was no one I would rather meet.”

Unity convinced her parents to send her to Germany to finishing school. (It was a lot cheaper than France, so she didn’t have to twist their arms too hard.) So, in 1934, she packed up her black shirt and headed for Munich. She didn’t spend much time in classes at Madame LaRoche’s finishing school, however. She devoted herself to mastering German and stalking Hitler instead, following his activities in the papers, chatting to the doormen at his building and lunching nearly every day at the Osteria Bavaria, his favorite spot in town.

“She would place herself so that he invariably had to walk by her,” recalled one of her friends who had accompanied her on these stakeouts. “She was drawing attention to herself . . . She’d talk more loudly or drop a book. And it paid off.”

She quickly infiltrated his inner circle, much to the chagrin of Nazi high command, who didn’t like having this young British girl present at their policy discussions. She called him “Uncle Wolf,” he called her “my little sunshine.” She introduced him to the whole family, save for her sisters Nancy (a quick-witted novelist too smart to fall for Hitler’s pageantry) and Jessica (who ran off with Winston Churchill’s nephew to fight the fascists in Spain). The British Broadsheets ran sensational stories about her with headlines like “She Loves Hitler” and “Peer’s Daughter as Jew Hater.”

Hitler rewarded her devotion by helping her find a new apartment requisitioned by a young Jewish couple, who wept when she said she would take it.

On Sept. 3, 1939, the day England declared war on Germany, Unity took a stroll through Munich’s Englischer Garten. She then took out a pearl-handled pistol and shot herself in the head. Hitler paid her medical bills and narrowly missed an assassination attempt leaving the Polish front to be by her side.

“He was deeply shaken by the fearful alteration to the beautiful, lively girl,” wrote one of the doctors. “Unity lay thoroughly apathetic and lamed in bed and took notice neither of the visitors whom she barely recognized, nor of the flowers they had brought.” She didn’t talk to hospital staff but spoke when Hitler visited, saying she wanted to go back to England. Her parents didn’t even know she was in the hospital till November.

Eventually, Hitler arranged to have Unity sent to a hospital in Switzerland, where her mother and youngest sister, Deborah, would travel to bring her back to England. When they sailed into Folkestone Harbour, on the English Channel, Lord Redesdale was waiting with an ambulance. British intelligence had kept tabs on Unity and wanted to question her and submit her for a medical exam, but the government intervened, saying that she and her family members “were to be treated as ordinary passengers.”

After she arrived back in Britain, rumors swirled about what actually happened to her in Germany. Some reporters said that Nazi Party members — wary of her proximity to Hitler — had shot her. Some observers didn’t believe she had been shot at all, since she didn’t appear to have any marks or injuries. Others speculated that she was pregnant and that her baby was Hitler’s. A great deal expressed outrage that the government never interrogated or interned her, especially when she was seen shopping in town or when she attended her sister Deborah’s wedding, to a duke, a year later.

Young gives credence to all these conspiracy theories, no matter how far-fetched. She seems particularly partial to MI5 superspy Guy Liddell’s conclusion that Unity faked the shooting in order to avoid answering questions about Hitler, for example. But she does offer some tantalizing breadcrumbs about Unity’s supposed pregnancy: an account that she spent time in a maternity house near her family’s home, and a 1940 Oxfordshire registry listing the birth of a baby boy to a mother with the last name Freeman, one of her father’s names. (Still, she allegedly had several Nazi lovers and there’s no proof she actually slept with Hitler.)

The bigger mystery is how this young woman — by all accounts charming, bright, fun — got so sucked into the Nazi cult, blithely spewing the most hateful anti-Semitic vitriol, making the most inane observations about how “sweet” Hitler and [chief propagandist] Joseph Goebbels were, treating all the degradation and murder like an incredibly thrilling, glamorous game. (Unity, writing about the notorious Night of the Long Knives, which she witnessed: “There were SS men dashing about the whole time on motorbikes & cars. It was all very exciting.”)

Unlike the other personalities in Young’s book, Unity did not take up fascism to preserve her powerful place in Britain, or out of fear of laborers’ rights and communism. She did it because she was bored and she wanted to shock people, and then she embraced it so fully that she really started to believe in it.

Unity eventually moved to Scotland, living largely in isolation until her death in 1948 from meningitis, caused by the bullet still in her brain. She was 33. At the time of her death, she still had a signed photo of Hitler. He had inscribed it: “You are beautiful. You are my everything. My heart will always belong to you.”

Read the full article Here