Sylvester Stallone stories before becoming ‘Rocky’ star

When Sylvester Stallone was born on July 6, 1946, something went wrong with the delivery.

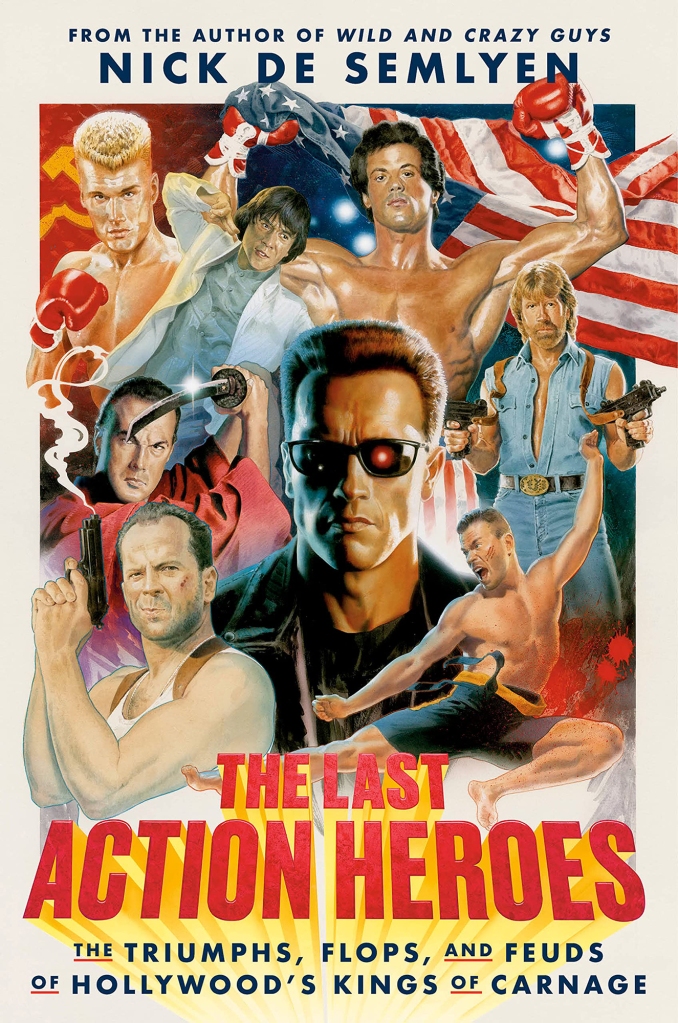

“The doctor on duty clamped forceps onto his head as he emerged from the womb and pulled, too hard, severing a facial nerve above his jaw,” writes Nick de Semlyen in his new book, “The Last Action Heroes: The Triumphs, Flops, and Feuds of Hollywood’s Kings of Carnage” (Crown, out now).

The mishap left a slight droop on the left side of his face, and caused the trademark speech impediment the actor would later compare to the “guttural echoing of a mafioso pallbearer.”

Stallone was taunted at school with nicknames like “Slant Mouth,” “Sylvia” and “Mr. Potato Head,” and later told reporters that his speech and appearance had left him “like a poster boy for a nightmare.”

Life wasn’t made easier by a physically abusive father who beat him and his brother Frank Jr. terribly while admonishing them, “Why can’t you be smarter? Why can’t you be stronger?”

The rage this caused led to a reckless nature. Stallone had broken at least 10 bones by age 12, and was voted by his teachers as, “Student Most Likely To End Up In The Electric Chair.”

But his young life was turned around at age 13, when he saw the movie “Hercules Unchained” starring the muscle-bound former Mr. Universe, Steve Reeves.

“It was like seeing the Messiah,” Stallone later recalled. “I said, ‘This is what I want to be.’ ”

Stallone became a workout madman, strapping cinder blocks to broomsticks to create barbells and turning every piece of furniture in his house into gym equipment.

He began lifting anything he could get his hands on at any opportunity.

When he arrived in New York in 1969 in his quest for fame and fortune, it was tough going from the beginning, including spending almost two weeks sleeping on a bus station bench, trying to ignore the junkies shooting up nearby.

By 1970, Stallone was earning $1.12 an hour shoveling lion dung at the Central Park Zoo.

As horrible as this sounds, it became even worse when the lions would occasionally urinate on him,

leaving an acrid small that would burn his eyes.

“Not too many people ever have the thrill of seeing lions taking giant leaks,” Stallone would later say.

“Let me tell you, they’re accurate up to 15 feet, and after a month of getting whizzed on, I quit.”

Meanwhile, Stallone, a prolific reader, initially thought that experimental theater would be his artistic path.

He was cast as a “Minotaur-like creature” in a production of “Desire Caught by the Tail,” a play written in three days in 1941 by Pablo Picasso, and the only play the legendary painter ever wrote, likely because it was horrible.

“The plot was non-existent,” writes de Semlyen.

“The characters were named things like Onion, Fat Anguish, and the Bow-Wows. There was to be simultaneous laughing and farting.”

For Stallone, the play’s awfulness became apparent when he saw his costume, which consisted of “red horns, a scarlet fright wig on his groin, and a huge fake penis.”

“It was a giant red appendage that you had to wrap around and stick in your G-string, because it was bothering you,” Stallone later recalled. “You really couldn’t walk.”

This clumsy apparatus did not always perform as expected on stage.

“One night, as [Stallone] hobbled around the ramshackle stage, the penis escaped its cloth prison and bounced up and down like a spring, provoking a wave of unintentional laughter,” writes de Semlyen.

“On a subsequent evening, Stallone ended up in the hospital after one of the other actors blasted a fire extinguisher in his face, freezing shut his lips and eyes. The incident saw the play close after a grand total of three weeks, and Stallone’s face turn an unnatural shade of brown for the next four months.”

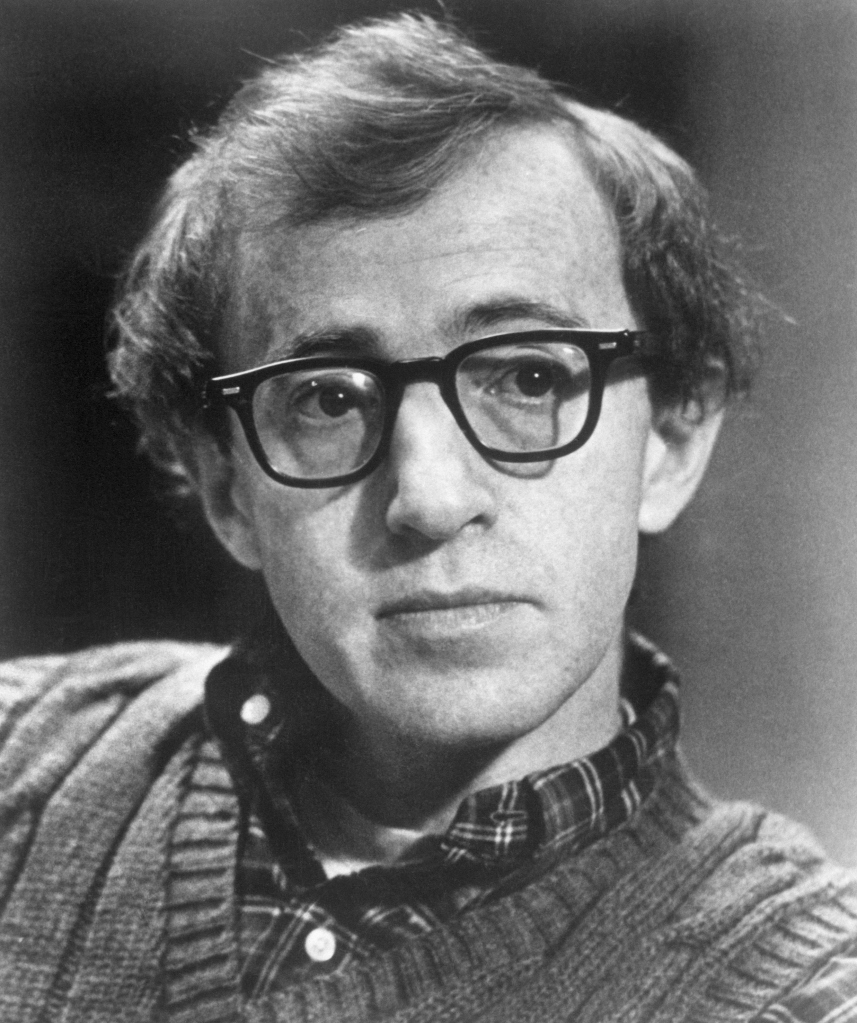

When he auditioned to play a mugger in the Woody Allen comedy “Bananas,” the screenwriter/director initially dismissed him as not intimidating enough.

Stallone, however, found a way to change Allen’s mind.

“Stallone and his friend Johnny, another aspiring actor, rubbed soot on their faces, ran Vaseline through their hair, and returned, scaring Allen into giving them parts,” writes de Semlyen.

Stallone began racking up small roles.

He was opposite Henry Winkler and Richard Gere as 1950s greasers in “The Lords of Flatbush,” but Gere exited the film after a skirmish that found him accidentally spilling mustard on Stallone’s pants, causing Stallone to send an elbow flying into Gere’s head.

Throughout this time, Stallone was also trying to make it as a writer, throwing every crazy idea he had at the wall while producing quick scripts under pen names like Q. Moonblood and J.J. Deadlock. His ideas were often outlandish.

One centered on a rock star suffering from a disease that could only be cured by bananas. Another was about frustrated unemployed actors who kidnap a producer and put him in a blender.

Eventually, he turned his attention to what he later described as “a vile, putrid, festering little street drama” about “a good guy surrounded by rotten people.” The main character, fighter Rocky Balboa, was inspired by real-life boxer Chuck Wepner, a little-known underdog who managed to last into the 15th round before losing to Muhammad Ali in 1975.

But even “Rocky” didn’t find the red carpet rolled out for its creator at first.

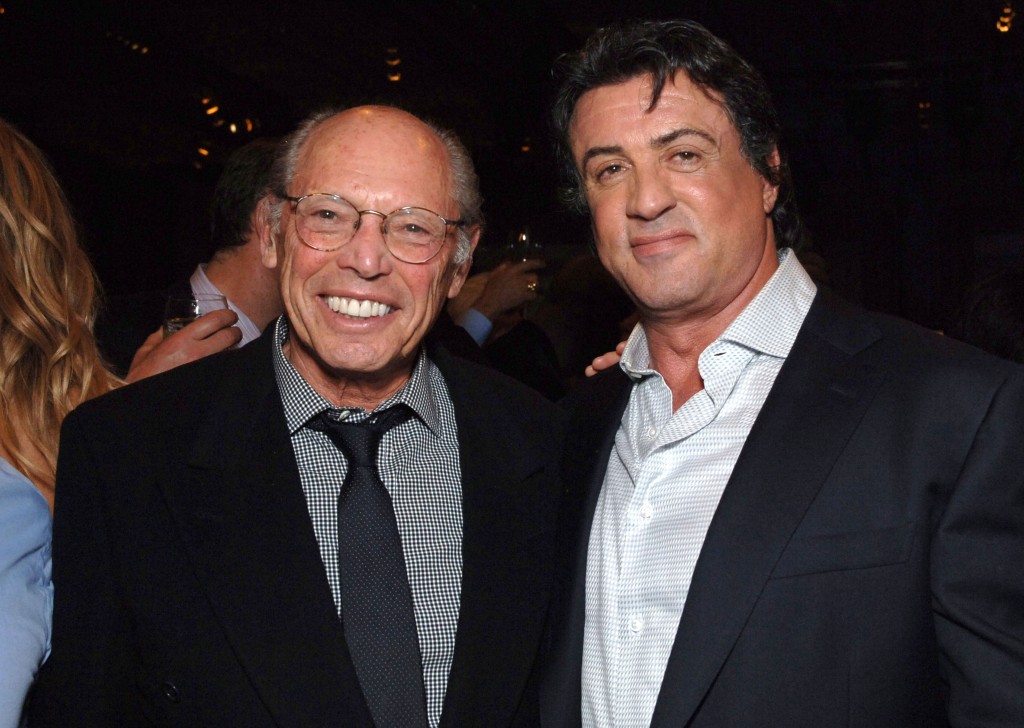

Irwin Winkler, the eventual producer of “Rocky,” thought little of Stallone after their first meeting, describing it as “one of those awkward meetings where you keep glancing at your watch and wondering how long it will be before you can ask him to leave.” But even after Winkler agreed to produce the film, the studio he had a deal with, United Artists, initially refused to consider it, wondering why anyone would want to see a movie about a bunch of “ugly ducklings.”

“This film comes along and says, ‘If you believe in yourself, there’s a wonderful opportunity for you.’ It told a story people wanted to hear at the time.”

Producer Irwin Winkler on the appeal of ”Rocky”

And Stallone made finding a deal even harder by insisting that he had to star in it.

United Artists, which had been hoping to attract Burt Reynolds or Ryan O’Neal to star, eventually agreed to let Stallone play Rocky if they made the film for a paltry $1 million — the same amount they had previously offered Stallone to simply sell them the screenplay and walk away.

This consolation, mixed with Stallone’s determination, turned Rocky into a legend.

The film became the top box office draw of the year, earning $117 million at the box office. It brought in more than hits “Taxi Driver,” “Carrie” and “Network” combined, earned Stallone Oscar nominations for Best Actor and Best Screenplay and won Best Picture.

Winkler credited the film’s success to a quality in much demand at the time, and one that Stallone had certainly exemplified on his road to Hollywood success: hope.

“We’d all gone through Vietnam, and the youth rebellion, and Nixon, and the plumbers and Watergate,” Winkler said in the book.

“And all of a sudden this film comes along and says, ‘If you believe in yourself, there’s a wonderful opportunity for you.’ It told a story people wanted to hear at the time.”

Read the full article Here