This double agent CIA and KGB spy was also a famous swinger

Long before Austin Powers was a randy spy, there was Karel Koecher.

Koecher was a Czechoslovakian émigré who lived in New York City from the 1960s to the ’80s. Although he spied for several competing agencies — the American CIA, the Soviet Union’s KGB, and Czechoslovakia’s StB — Koecher was most memorable as an eager participant in the East Coast’s early sex-club scene. And he was anything but under the radar.

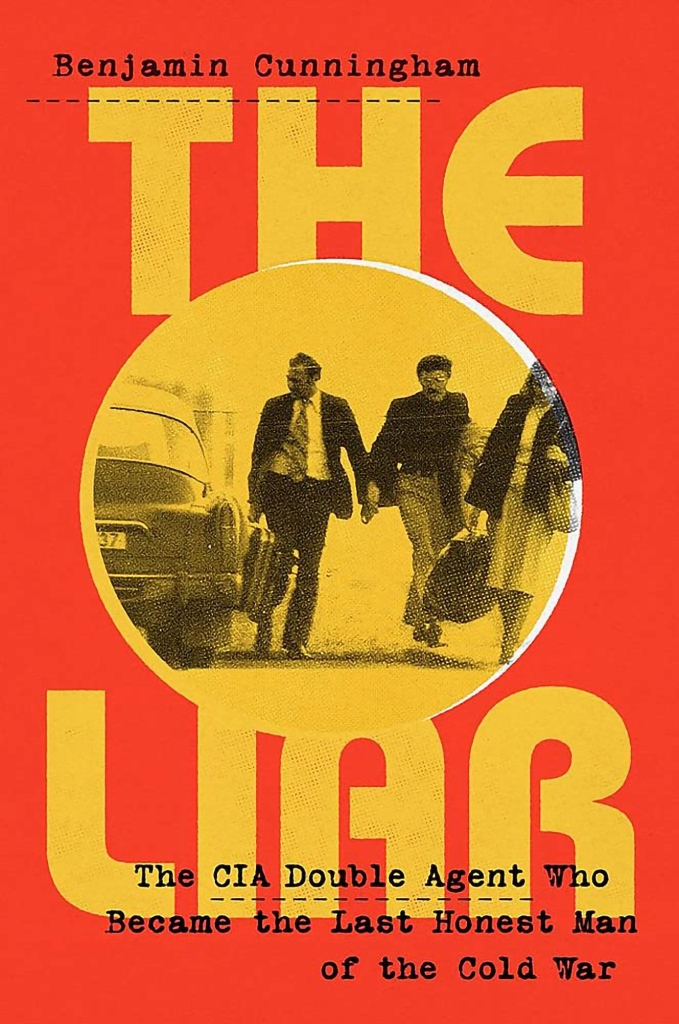

“Koecher was a bit strange. Usually people keep their clothes on at least some of the time, but he was always walking around naked,” recalls a fellow orgy guest in “The Liar: How a Double Agent in the CIA Became the Cold War’s Last Honest Man” (Public Affairs, August 23rd) by Benjamin Cunningham. “And he always had an erection.”

While Koecher was an enthusiastic swinger, he was a reluctant spy. Born in 1934 near Prague, he was unhappy with Czechoslovakia’s socialist turn after World War II, and so fought against its Communist Party.

Koecher was rebellious — he called himself an “extreme individualist” — and had numerous clashes with the Czech state police throughout the 1950s, many related to his libido. He was given a one-year suspended jail term for bitterly calling local police “peeping Toms” after they caught him canoodling with a girlfriend. After the StB later trumped up charges that Koecher “violated the moral code . . . of underage girls” he received two more years of probation.

The police harassment didn’t stop. Although an excellent student and speaker of four languages (English, French, Russian and Czech), Koecher was initially kept from attending university, forbidden from accepting a fellowship in Cameroon (so he couldn’t defect), and in joining the Communist Party (which he did solely in the hopes of finding better jobs).

Eventually, Cunningham writes, Koecher realized “He could not beat them, so …. had little choice but to join them.”

With help from a friend inside the agency, Koecher joined the StB in 1963. The agency’s assessment wasn’t glowing, calling Karel “over-confident, hypersensitive, hostile towards people, money-driven … with an antisocial almost psychopathic personality.”

When the StB warned Karel to tell no one about his new job, he immediately confessed it to his new wife, Hana. (He did the same thing when a later lover wanted him to leave Hana for her — “I can’t,” Koecher shrugged, “I’m a spy.”)

Still, between his language skills and connections in the West honed from years working as a Prague tour guide, the StB had no better candidate to send to the US. After two years of doing little in Czechoslovakia, the StB sent Karel to New York to “penetrate the CIA.”

Asked how, the StB said, “That’s up to you.”

With his connection to Professor Charles Kline from an earlier Prague tour, Koecher attended Columbia University and earned a PhD in 1971. Columbia’s job-placement service then suggested Karel apply for a job . . .at the CIA. Soon Koecher was translating Russian documents for America’s foremost spy agency, all while still working for the StB and their superiors at the KGB.

When the CIA targeted Soviets in the US to recruit, Koecher “more or less sabotaged their efforts by telling the Soviets who the targets were.”

But Koecher was never all that enthusiastic about the job. “The StB urged him to inform on coworkers . . . but he never really got around to it,” Cunningham writes.

The problem was that Karel was a perfect representative of the 1970s “Me” decade.

“It is about loyalty to yourself. . . . I don’t give a f–k about belonging,” he said.

Koecher’s primary interest was instead New York’s sex scene. With Hana — whom others described as “strikingly beautiful” and “incredibly orgasmic” — the Koechers regularly attended nightclubs like Studio 54, in addition to swingers clubs like New York’s notorious Plato’s Retreat, Capitol Couples Club in Washington, DC, and an upstate nudist colony called Stockholm. Plus, “At least once or twice a week, Koecher and Hana had one or two couples over for dinner, or went to their homes, to swap spouses for sex,” Cunningham shares. America’s libertine life was eagerly welcomed by the couple who had grown up behind the Iron Curtain.

Koecher always believed the StB didn’t pay him enough, so he regularly ignored meetings with them and occasionally told them to “f–k off.” He had no complaints about his Soviet stipend, but to protect his own role a KGB general who was also a CIA mole raised doubts about Karel’s loyalties. That got Koecher decommissioned by both Communist agencies. By the mid-70s, his career was kaput.

“The double agent was an agent no more,” Cunningham writes.

The KGB did recommission Koecher during the Reagan administration, to use his connections in New York society to pursue “informed gossip” from people working in U.S. government.

“I would socialize for socialism,” Koecher said.

By then, the FBI was on Koecher’s trail — his wild spending of KGB cash raised their suspicions — and in 1984 the net was closing. The night before they were arrested as spies, Karel and Hana Koecher brought a friendly couple back to their apartment.

“On their last night of freedom in the U.S., FBI wiretaps confirm that Karel and Hana went down swinging,” Cunningham writes.

As a spy, Koecher faced the death penalty, but after being detained for 2 years — when prosecutor Rudy Giuliani failed to make a case stick — US and Soviet authorities swapped the Koechers for Jewish dissident Anatoly Shcharansky on the Glienicke Bridge, a k a the “Bridge of Spies.”

Banned from ever returning to the US, the swinging spy’s days of American decadence were done.

Read the full article Here