Who killed Stanford U founder? New book solves Jane’s murder

Jane Stanford’s death was one of the most sensational of the 20th century — and now, more than 100 years later, a new book offers enough proof to call it murder.

Stanford, beloved by her community, survived the deaths of her husband and son while keeping her family’s namesake university afloat with her own money. She seemed like the unlikeliest of murder victims when she died in Hawaii, spasming and vomiting, poisoned by strychnine.

Who would want to kill a generous old lady?

Plenty of people, according to a new book by veteran historian Richard White. There are so many possible suspects in “Who Killed Jane Stanford?” (W.W. Norton) that the book reads like a game of “Clue” — among them, a disgruntled university president, an overworked personal assistant, a recently fired “manservant” and a handful of aggrieved housekeepers.

So, who killed the rich old lady in the Honolulu hotel room with the rat poison?

White scoured the archives in search of answers. “Rarely have I encountered more documents that have vanished and more collections and reports that have gone missing than in this research,” writes White.

Luckily for readers, White has solved the mystery and the record can finally be set straight on this century-old cold case.

(Be warned: Spoilers abound.)

Jane’s husband Leland Stanford made his money in railroads — and according to White, this wasn’t a clean way of building capital. It took a fair share of “lying, cheating, self-dealing and backstabbing.”

The idea for a university came after the death of his son, who died of typhoid before his 16th birthday. According to lore, Leland Stanford Jr. asked his father to start one on his deathbed.

The Stanfords were far from intellectuals — Leland Stanford was known for using his library as a place to nap — but they followed through and opened Leland Stanford Junior University to men and women in 1891. Two years later, Leland Stanford died. From that point on until Jane Stanford’s death in 1905, the university was hers.

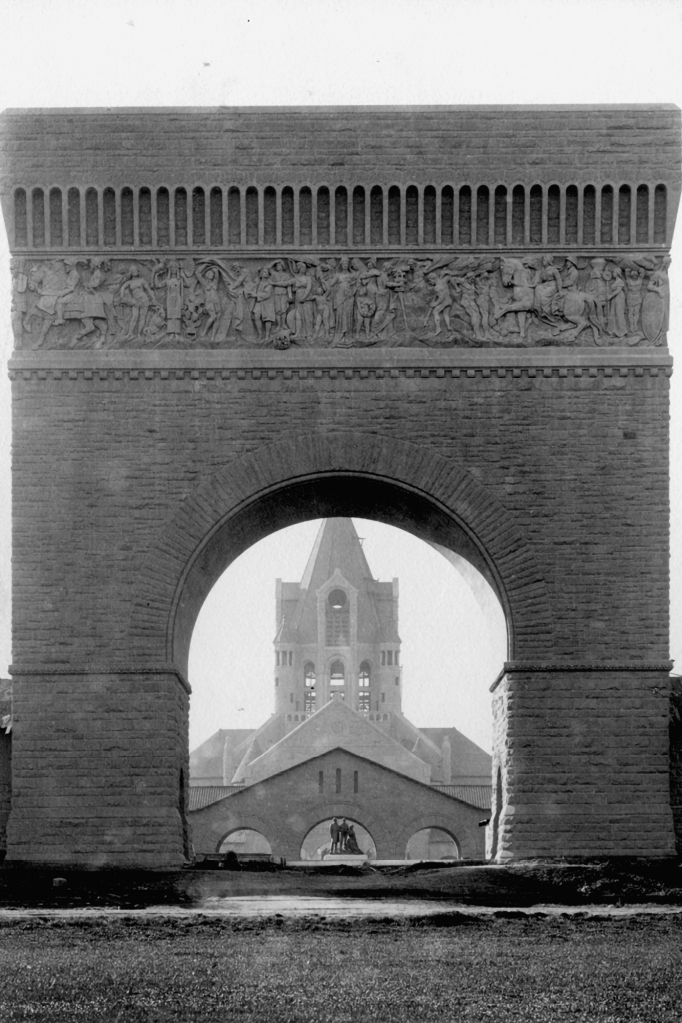

“She commissioned the statue of her family; she built the arch and church. She dedicated the church to Leland Stanford — ‘my husband,’” writes White. Every part of the university from its design to its educational standards reflected back on its benefactress.

“Jane Stanford regarded a classical education as useless and cruel,” writes White. “Graduates of Harvard and Yale, she claimed, were of benefit to no one, including themselves.” Her university would prepare students for their “usefulness in life” as well as the education “of the soul as well as the mind.”

She even successfully combated a legal challenge to the Stanford estate that put university funds in jeopardy. As the wife of the school’s president and a future murderer suspect would later say, Stanford would have “given her life, if necessary, to save the university.”

An apt statement if there ever was one.

The first sign of something amiss came on Jan. 14, 1905.

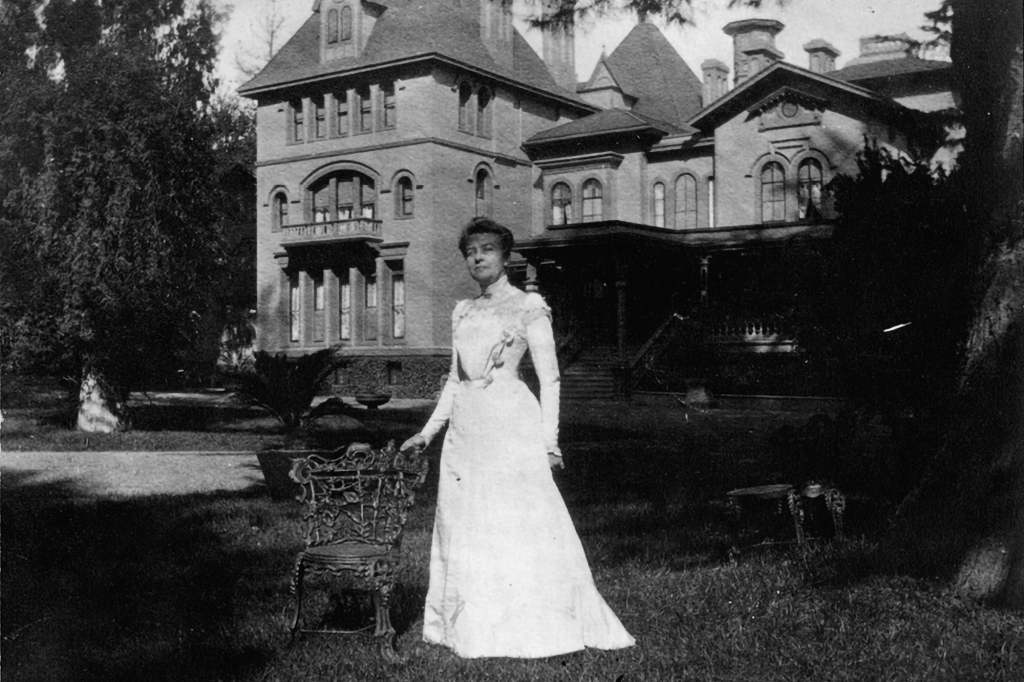

Jane Stanford went to bed early in one of the 19 bedrooms of her 41,000-square-foot mansion in San Francisco. She was reportedly the wealthiest of all her moneyed neighbors.

Stanford drank from a bottle of Poland Spring Water, which claimed to cure all manners of nervous illnesses and diseases. When Stanford took a sip, she vomited. The water was bitter. She called out for help and a maid named Elizabeth Richmond came. Her personal secretary, Bertha Berner, who slept on the floor above Stanford, followed.

Stanford wretched and spasmed that night, but pulled through. The next day she sent the bottle away to be tested for poison. It came back positive for strychnine — in a readily available and highly bitter form used as rat poison.

This was bewildering to Stanford.

“I did not think anyone wished to hurt me. What would it benefit anyone?”

The reality was that she had made many enemies. Her maid had recently threatened to quit over mistreatment. Another staff member, Ah Wong, held a grudge because Stanford owed him money.

And then there was her personal secretary. Berner had worked with Stanford since the death of Leland Stanford Jr. and the two were close. Stanford considered her relationship with Berner to be “one that cannot be bought, it is God-giving.”

In fact, Berner had nearly walked away from the job several times after quarreling with her boss; one regular source of strife was that Stanford would often not allow Berner to visit her ailing mother. Other arguments involved men. Berner, a young, attractive woman in her thirties had many admirers and an active social life — too active for Stanford’s old-fashioned tastes. When Stanford insisted that Berner live with her in her Nob Hill mansion, it made “her relationship with Mrs. Stanford even more claustrophobic.”

These were just the people under her roof. Others included a “manservant” named Albert Beverly who had traveled with Stanford until he was cut loose for inflating his bills and skimming off the money for himself.

And then there was the friction between Stanford and the university’s president, David Starr Jordan, who disagreed with Stanford on almost everything about the school. Jordan hated the fact that he owed his job to a dead child. He also knew about Stanford’s secret interest in spiritualism, a practice of communing with the dead.

But the thing he hated most was having to follow the orders of (in his words) “one aged woman.”

“She controlled the endowment, the school’s growth, its construction, and its priorities,” writes White. She put her finger on scale on almost every matter pertaining to the day-to-day running of the university: Staffing, coeducation (she was not in favor of educating women with men), even petty things, like the installation of doorstops in the chemistry building.

“Jane Stanford wanted to be loved and admired, but she needed to be obeyed. Obedience was the condition of working for her,” writes White. Jordan was not obsequious enough for Stanford — and he knew his head was on the chopping block.

Despite the long list of possible leads, the San Francisco Police Department was as flummoxed by the poisoning as Stanford was. Berner was cleared of any wrongdoing and the maid Elizabeth Richmond was fired. No arrests were made.

Jane Stanford wanted this scandal to disappear as much as the college and the police department did.

But the story doesn’t end there.

A little over a month later, Stanford died in Hawaii with Bertha Berner by her side.

They were in Hawaii on their way to Japan. Berner, whose mother was seriously ill, did not want to go. “She was not eager to be dragged off to Asia in the company of an imperious and rich woman,” writes White.

Before they left San Francisco, Berner visited a pharmacy and bought three ounces of bicarbonate soda, a treatment for indigestion that Stanford often used.

In Honolulu on Feb. 28, 1905, Stanford had a pleasant picnic before retiring to her room to lie down. She requested the bicarbonate soda, which Berner brought to her. Later she called Berner to her room. “I am so sick,” she said, wracked with spasms. Berner called for a doctor.

White describes the classic symptoms of strychnine poisoning: “Jane Stanford could not swallow. Her jaws were set . . . Spasms overcame her.”

“This is a horrible way to die,” Stanford said before she stopped breathing. When she did, her body went rigid and the soles of her feet turned inward with the insteps arched.

The Hawaii police department, physician and chemist announced that Stanford had been poisoned — this time with a more potent form of strychnine that could only be purchased at a pharmacy.

The press had a field day with the death — producing lurid front pages of the various murder suspects and even floating the idea of suicide thanks to her interest in spiritualism.

‘Jane Stanford wanted to be loved and admired, but she needed to be obeyed. Obedience was the condition of working for her.’

Author and veteran historian Richard White

Meanwhile, the Hawaii side of the investigation continued. They discovered that Berner would receive $15,000 from Stanford’s will. Berner also had a relationship — likely romantic — with manservant Albert Beverly, who had been fired for getting kickbacks that Berner also got a piece of.

But powerful people didn’t want the charges to stick. No one in the administration wanted the University’s dirty laundry aired. University president Jordan became the face of the counter-narrative that Stanford died of “natural causes.” Jordan introduced his own physician who produced “evidence” that showed that Stanford likely died from “angina pectoris,” or overeating. The considerable gas from overeating at lunch “would have created pressure on the heart,” the physician argued with a straight face.

Berner’s account changed, too. Instead of rigid, Stanford was now slumped over. She “passed away peacefully,” Berner said.

Despite a coroner’s report that found poison in her system, Jordan announced that she died from “advanced age, the unaccustomed exertion, a surfeit of unsuitable food, and the unusual exposure of the picnic party.” Detectives dropped the case, as an investigation “would not benefit the estate, the university, or the San Francisco police,” who would be ridiculed for their mishandling of the first poisoning and overshadowed by the inexperienced Hawaiian police.

Jordan worked at Leland Stanford Jr. University for 11 more years. And although a cloud of suspicion hung around Berner, she lived comfortably in Menlo Park thanks to the $15,000 Stanford inheritance. In 1935, Stanford University published Berner’s story called “Mrs. Leland Stanford: An Intimate Account.” The book is riddled with inaccuracies, “wrong in almost every detail” of Stanford’s death, and became key to White’s case against her.

“Berner’s lies and omissions did not spring from forgetfulness,” Write writes. Particularly, Berner’s omission of the pharmacy stop was particularly “critical to the mystery,” White writes.

“Two poisonings, two doses of strychnine, Berner the only person present both times, plus her purchase of the bicarbonate that later contained the poison: all this spells trouble for Bertha Berner,” he writes. This along with their rocky relationship led White to conclude: “I think she was a murderer, but up until the moment of the murder, I can’t help sympathizing with her.”

Along the way, White discovered an unexplored lead: Palo Alto pharmacist PJ Schwab who sold her the bicarbonate soda. Schwab, who had been accused of another financial crime, was located close to Berner’s mother’s house. Berner and Schwab both spoke German and were linked romantically. “He becomes for me the key to the whole mystery. Insert him in the narrative and things start to click into place. He worked in one of the Palo Alto pharmacies and was friendly with Berner. Accused of embezzlement, he was clearly a man willing to take chances and he could have gotten her the poison without leaving a record.”

Now that we can track the murder weapon to Berner is the case closed? Did she act alone?

Not exactly.

White believes that the university’s president was involved — he didn’t poison Stanford, but instead was an “accessory after the fact.”

Jordan convinced Berner to change her description of Stanford’s death to help suit his aims. “Jordan saved Berner because he had to in order to save himself, the will, the trust documents, and ultimately the university,” writes White.

“In an age of surreal conspiracy theories, it is a reminder that conspiracies can be quite real.”

Read the full article Here