Why Jay Gould was among the most hated men in Gilded Age America

Born in poverty in 1836, Jay Gould became one of the richest men in Gilded Age America but had few admirers. This was mostly because the Wall Street financier would do anything to make a buck: flouting laws, manipulating stocks, bribing officials, backstabbing friends. No one was surprised in the spring of 1873 when an investor rushed Gould’s table at Delmonico’s and punched the “Little Wizard” in the nose. The New York Times went as far to suggest that the “flattening of Gould’s nose” might be “an hourly occurrence.”

To profit personally, “[Gould] would bring pain to everyone with money in the market,” Greg Steinmetz writes in “American Rascal: How Jay Gould Built Wall Street’s Biggest Fortune” (Simon & Schuster), out now.

When a railroad that employed Gould as a surveyor stopped construction because of an impending lawsuit, he piped up at a meeting — standing just 5-foot-1 and aged just 17 — to suggest building the railroad immediately, legality be damned. Gould had a crew and could begin that day, he told railroad executives. The railroad agreed, and Jay Gould’s career of operating by hook or crook was underway.

He worked tirelessly, often going days without sleep, and he eventually made himself sick. Recovering from typhoid fever at 20, he toiled at a general store, making friends with its owners. But when a customer wanted to sell the owners a valuable piece of land, Gould bought it himself. That cost him a job, but when he flipped the acreage he did net a $5,000 profit ($100,000 in today’s dollars).

In 1856, a rich tannery owner named Zadock Pratt wanted Gould to survey his properties, but the young man suggested going into business instead: Gould lied about a forest of hemlocks (necessary for tanning) where they could build a new facility. Pratt agreed, so Gould roamed the wilds of Pennsylvania searching for that forest. He found it, and a tannery co-owned by Pratt and Gould was built. Gould sold the tannery’s leather hides to Pratt for resale, until Gould realized he could get a better price in New York City. That ended the partnership, but increased Gould’s profits.

Gould didn’t meet the Union Army’s 5’3” height requirement, so he spent the Civil War operating in New York City, where he realized there was more money in buying and selling hides than producing them. He left tanning behind to enter the “smoky world of stocks and bonds.” On Wall Street, “brains and information … won the day,” Steinmetz writes, and no one was better than Gould. “He was more methodical, more voracious in search of insights, and more patient with minutiae.”

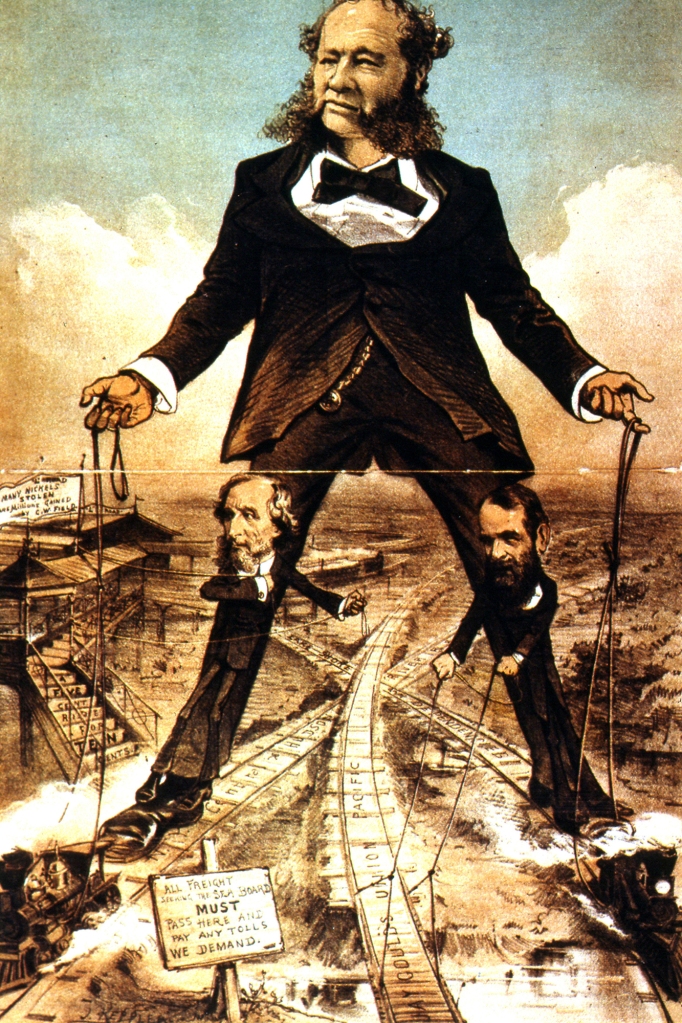

Gould began investing in railroads in 1859 — he’d eventually control one in every six miles of American track — and greased the palm of Tammany Hall’s Boss Tweed for help. When Cornelius Vanderbilt and Daniel Drew began battling for control of the Erie Railway, Gould snookered them both. While Vanderbilt was trying to buy up all Erie stocks, Gould bribed a judge to allow more certificates to be printed and fleeced Vanderbilt out of nearly $7,000,000. An irate Vanderbilt got another judge to issue an arrest warrant for Gould, forcing Gould to flee Manhattan to New Jersey by rowboat one night with satchels overflowing with Erie cash. Later, Gould snuck into New York to bribe state officials in Albany — he reportedly arrived with a trunk “literally stuffed with $1,000 bills” — and bought his way to freedom. A peace accord was reached with Vanderbilt and Gould was installed as Erie’s new president.

After that “Great Erie War,” Gould’s name was made.

He was orchestrating some of the most ruthless moves in Wall Street history, including trying to corner the gold market in 1869 — the first “Black Friday.” While Gould made some money in that mostly failed effort, the attempt sullied the reputation of President U.S. Grant (thought to be in cahoots with Gould), left banks on the verge of collapse, and threatened the entire US economy.

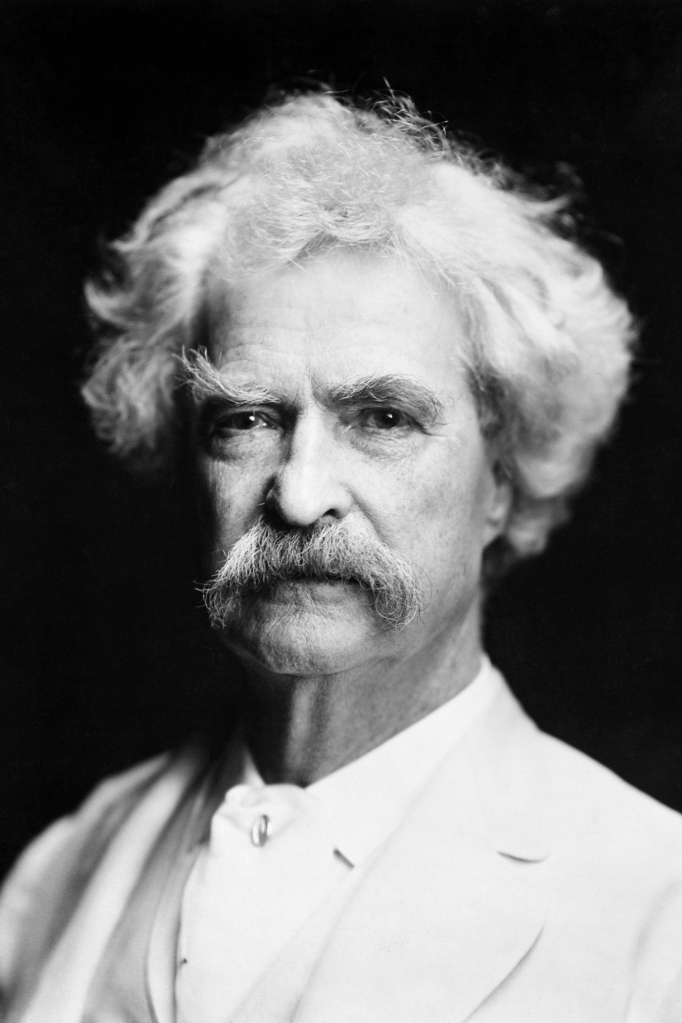

Gould didn’t care. He believed his ambition was “divine, a true and noble and necessary path.” While Cornelius Vanderbilt considered Jay Gould “the smartest man in America,” most felt differently. Given Gould’s worship of money, Mark Twain characterized him as “the mightiest disaster that has ever befallen this country.” Newspapers variously labeled him “Mephistopheles,” “a ghoul in human form,” or “the most sinister figure ever to have flitted bat-like across the vision of the American people.”

Gould did play by his own rules. When he wanted to buy the Manhattan Railway — a.k.a. New York City’s elevated trains — he had his New York World newspaper spread stories about its imminent demise, making the stock price plummet. He then gained control by buying its stock on the cheap, with the World subsequently running stories touting the railway’s overall health, causing the stock price to dramatically rebound. Within six months the stocks Gould bought for a million bucks were worth 2.5 times that.

“It was one of the best investments he ever made,” Steinmetz writes.

Over the course of his notorious career, Jay Gould’s Machiavellian moves led enraged investors to not only punch him at Delmonico’s, but throw him down a set of Broadway stairs, and threaten him with a pistol. He was arrested three times but never spent a day in prison, always buying his way out of trouble. Gould died of tuberculosis in 1892, aged 56, worth a fortune estimated to be billions in today’s dollars.

Read the full article Here