Why we should stop casually prescribing antidepressants to teens

In July of 2001, when I was 15, my father passed away. Two months later, it was Sept. 11, followed by a move from my childhood home. Somewhere during that time, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, and my grades began to slip. My mother insisted I see a child psychologist, who referred me to a child psychiatrist. The latter prescribed me a cocktail of antidepressants designed to combat my now-diagnosable supposed mental illnesses: major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

Fifteen years later, I was 30 years old and still on the same cocktail of drugs prescribed to me as a teenager. I spent my nights staring out my Manhattan high-rise window, contemplating how long it would take my body to hit Third Avenue. Despite the 10,000 antidepressants I’d taken in my adult life, I was more depressed than ever.

In a moment of clarity, I decided to see a new psychiatrist and get off the antidepressants. Maybe I’d be worse without the drugs in my system; maybe I’d be better. I just knew that whatever I was doing wasn’t working.

On the advice of my psychiatrist, I stopped taking my 37.5mg of Effexor XR, the smallest dose on the market. Within days, I began to experience sensory overload, unrelenting mood swings and violent thoughts about harming myself and others. I bent a metal ironing board in half out of rage, developed a stress-induced autoimmune syndrome, and beat my thighs until they turned the color of plums. On the outside, it looked like I was having a psychotic break. But I knew the truth: this was antidepressant withdrawal, and its origins could be traced to the swift decision to prescribe antidepressants as a remedy against normal human emotions surrounding grief, trauma and change.

Now, I worry that the declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health will add to already record-breaking psychiatric drug prescriptions for young adults, putting countless people at risk of following in my footsteps.

Recent research of 80,000 global youths estimated that child and adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, this correlates with an increase in psychiatric drug prescriptions in young people. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry showed a 15.6% increase in antidepressant prescriptions between March 2020 and February 2021 for adolescent females.

In the UK, the Sussex Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services prescribed 22% more prescriptions for antidepressants between March 2020 and March 2021 than it did between March 2019 and February 2020. Data are scant on American pandemic-related prescription rates due to our decentralized medical system, but it’s not unreasonable to assume similar trends, especially given the rise of tele-prescription companies, most notably Cerebral (which is currently being investigated by the Department of Justice for prescribing addictive, controlled substances like Xanax after 30-minute tele-evaluations.)

I am not a doctor, nor am I a parent. All I can offer is hindsight on my own experience.

My father’s sudden death and my subsequent introduction to the hazy world of antidepressants dropped me into an alternate reality at a time when I was forming the foundation of my identity. This psychiatric intervention sent a message that something was wrong with me and that the only “fix” was medication — when what I needed was time to process what had happened to me. I needed a psychologist or counselor who saw me as a whole person who had experienced something terrible, not as a walking diagnosis in desperate need of returning to “normal” in a world that was not normal.

I know that grief — and all emotional pain — waits for you until you’re ready to do the work. The drugs may have succeeded in dulling my emotions, but it robbed me of the opportunity to learn resilience, arguably the most important lesson of young adulthood. In absence of this resilience, each of life’s subsequent hits broke me down a little more. These issues compounded into a lifelong struggle that was far more difficult for me to overcome at 30 than it would have been had I been allowed to grieve — and maybe even struggle for a while — at 15.

Today, I’m 36 and fully recovered from depression. I never did go back on another antidepressant. Fifteen years of numbness, a year in severe antidepressant withdrawal, and two years of re-building my life wasn’t exactly a glowing advertisement for their long-term efficacy. Besides, I was due for a lesson in resilience. And I sure as hell learned it.

It’s no secret that many young people are struggling, and perhaps these drugs are useful in the very short term for extreme cases that have exhausted all other options. But our mental health trends have only worsened since we began dosing children and teens with antidepressants in the ’90s, indicating that this strategy isn’t working very well. Given the possibility of devastating withdrawal and the known long-term side effects of antidepressants, including permanent memory loss and sexual dysfunction, it baffles me that the first line of defense for so many kids is still serious pharmaceutical intervention.

Instead, maybe there’s value in letting young people process all that they’ve experienced, even if it takes longer than is convenient and gets a little messy. Had I been given that opportunity, maybe I wouldn’t still sometimes find myself in limbo between the 15-year-old who was medicated and the 36-year-old trying to make sense of the mess. In those moments, I can’t help but wonder, who might I have become?

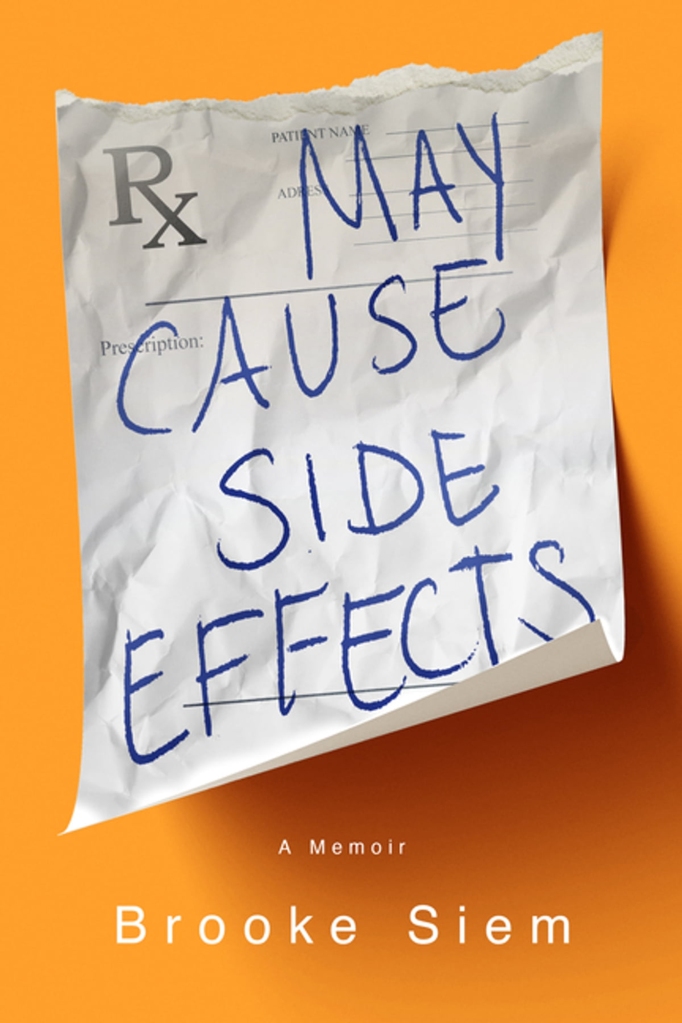

Brooke Siem is the author of “May Cause Side Effects: A Memoir,” available wherever books are sold. Find her on Twitter at @brookesiem.

Read the full article Here