Why working at Disney, the ‘Happiest Place on Earth,’ is misery for many

Gabby Alcantara-Anderson, 31, has worked at Disney World in central Florida for almost a decade. But she still struggles to make ends meet.

A long-time supervisor at Magic Kingdom attractions like Thunder Mountain and Tom Sawyer Island, she lives with her husband, Zac —who also works for Disney, in transportation maintenance — and teenage daughter Chastity in a small three-bedroom house that she rents from a relative. Their combined salaries, in the low five figures, are barely enough to pay the rent or put food on the table.

“There have definitely been times when it’s like, ‘OK, kids, there’s rice for tonight, then rice tomorrow, but there will be different sides with the rice,’ ” she confided to author and NYU cultural studies professor Andrew Ross in his new book, “Sunbelt Blues: The Failure of American Housing” (Metropolitan Books), out now.

She has no savings, no nest egg, and sometimes not enough gas money to make the hour-and-a-half commute (one way) to the Magic Kingdom. On nights when she doesn’t have enough cash to make it home, she sleeps in the parking lot. When she does make it home, it’s usually after midnight, and she has just enough energy left to cook dinner for her family for the next day.

But despite Alcantara-Anderson’s financial struggles, it’s never stopped her from loaning cash to fellow “cast members” (as Disney employees are) who can’t get enough to eat.

As she told Ross, there are at least nine guys on her team who live in the same two-bedroom apartment, with air mattresses, sleeping bags and a couch. “They rotate through who gets the bed on certain nights,” she says. “They only have one bathroom, so they have to ration shower time, and their clothes are all in trash bags.”

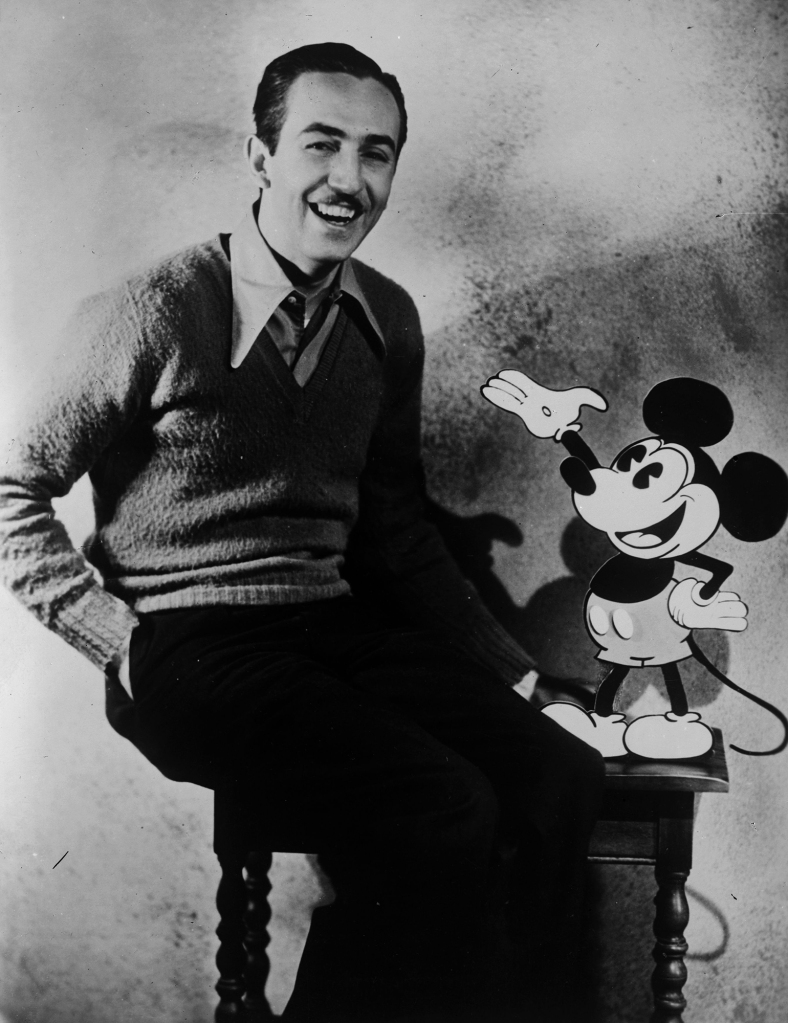

Their grim living conditions make for a stark contrast with Disney World’s reputation as the “Happiest Place on Earth” — not to mention the most profitable. During the first few months of 2022, the Walt Disney Company already netted $29.8 billion in revenue, the second-best quarter of all time for the company. Some $7.2 billion of that came from Disney parks. And yet most of the 78,000 workers at Disney World’s four parks “are paid a poverty wage,” Ross writes. (Walt Disney World did not respond to a request for comment as of press time.)

It’s not just a Florida problem. A 2018 study by Occidental College and the Economic Roundtable looked at working conditions for employees at Disneyland — the company’s original park, in Anaheim, Calif. — and found that more than half worried about being evicted from their homes, and more than one in 10 had been homeless in the last two years.

“Disney ideally wants the guests to believe theme park employees are happy-go-lucky kids doing this job for fun,” says Alcantara-Anderson. So the company takes pains to conceal the fact that “most of us are career employees who have pensions, at least if we are union, at the end of our work lives,” she says.

Many are forced to stay at any of the “extended stay” motels in the area, Ross writes.

Like Ramona Gutiérrez, a short-order cook at one of the Magic Kingdom’s biggest restaurants — she declined to name it — who lives at HomeSuiteHome, a notorious motel whose owner once (unsuccessfully) sued the sheriff in 2015 for not evicting enough of her tenants.

“I never felt safe,” Gutiérrez told Ross about her experience at the motel.

“It was crawling with bedbugs, and then the ceiling collapsed on me. All this time I was working at the happiest place in the world and felt fulfilled in my job.”

It’s this irony that Ross encountered the most when interviewing Disney employees, the fact that they both felt victimized by their jobs and completely enraptured by the pixie dust. Alcantara-Anderson, for all her talk about the hardships that she endures because of Disney World, doesn’t hesitate to mention the joy she felt “the first time I moved a guest to tears,” letting a young visitor win at checkers and then giving him a Fast Pass as a reward.

But, Ross adds, these same employees “seemed perfectly capable of separating that emotional allegiance from their indignation about the mismatch between their low wages and area rents.” Some even admitted how the demands to remain eternally happy had wrecked havoc on their health.

Brian, who operates the Splash Mountain ride at Disney’s Magic Kingdom, admitted that he “has trouble finding the real me” after dropping his happy workplace face at the end of a shift. His co-worker Laura forewarns her husband “to give me 20 minutes” after she returns home from a shift, “to deal with when I am screaming inside from the hurt and anger,” she told Ross.

“It takes lots of mental fortitude to maintain that persona,” says Alcantara-Anderson, especially when you do not have a sunny disposition, or “when there are personal troubles in your life.” And customers aren’t always forgiving. Alcantara-Anderson says she frequently receives complaints like, “That cast member doesn’t look too happy” or “What’s wrong with her magic today?”

It isn’t enough for an employee to be constantly brimming with pixie dust giddiness. It needs to feel authentic. “Visitors are always on the lookout for fake emotions,” Ross writes. “They have paid through the nose to visit an artificial landscape, but they want real responses from the greeters, guides, and attendants.”

It’s a veneer that isn’t always easy if you slept in your car last night, or if you’re not sure how you’re going to feed your family or pay rent next month.

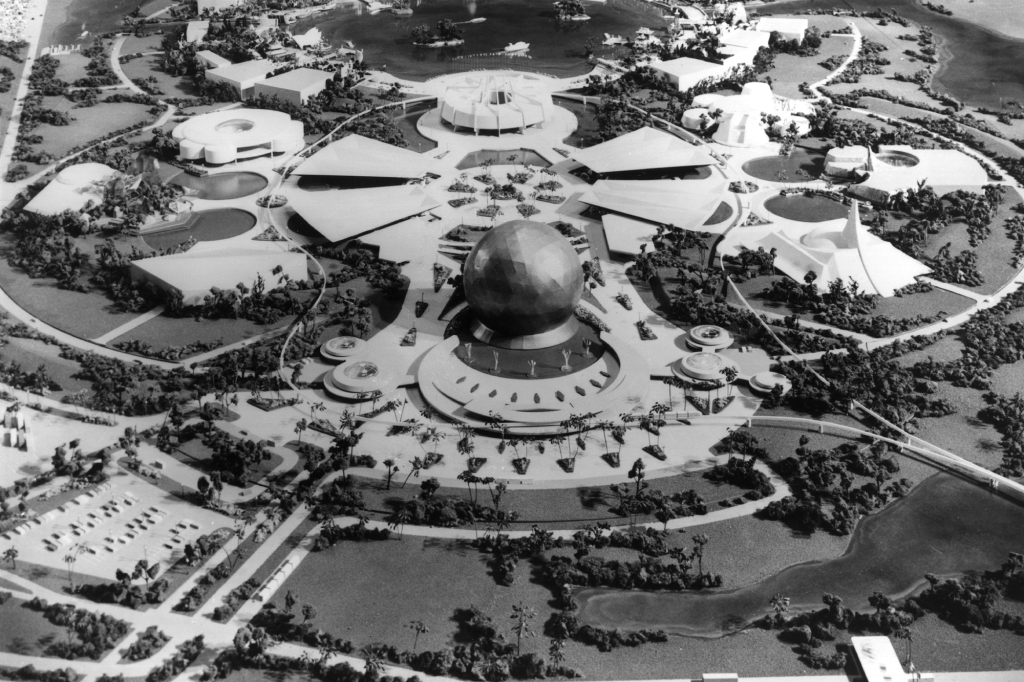

When Walt Disney first unveiled EPCOT — short for Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow — he imagined it, as he explained in a 1966 short film, as a a solution “to the problems of our cities.” The 27,400 acres, or 43 square miles, of central Florida that the Disney Company acquired a few years earlier would be used to create a utopia with “no slum areas” and “no landowners . . . People will rent houses instead of buying them, and at modest rentals.”

Had this promise been carried out, Ross writes, “it would at least have created a kind of company town, guaranteeing affordable housing for Disney World employees.” But this isn’t what happened. Instead, the Disney corporation was granted a wide-ranging charter where they basically got to control their own utilities, policing, and fire service. “It is effectively a puppet government,” Ross writes. (Though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis promised to revoke that power back in April, nothing is official yet and the conflict is still ongoing.)

Since 2018, Disney has purchased another 3,000 acres of land. But most of it, including the land they acquired in the ’60s, remains undeveloped.

As for the “modest rentals” that the late Walt promised, they never materialized. “Disney’s response to its employees’ acute housing needs has been dismal,” Ross writes. The company “could easily make some of its large parcels of surplus land available for housing, either for its own workers or for others who need it.” But instead, Disney has remained true to its “Grinch-like reputation, which dates back decades.”

Even Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Walt’s brother Roy, has been critical of the company’s treatment of employees. In a 2019 interview, she went after Disney CEO Bob Iger — whose 2018 earnings, roughly $65 million, were 1,424 times the amount earned by a typical Disney employee. “He deserves to be rewarded,” she said, “but if at the same company people are on food stamps and the company’s never been more profitable . . . how can you let people go home hungry?”

Mike Beaver, a longtime Magic Kingdom employee and union member, shares Abigail Disney’s outrage. Although he’d been employed at Tomorrowland in Disney World’s Magic Kingdom for 21 years, by 2018 his finances had hit such rock bottom that he moved out of his home and into a motel, sharing a room with a friend at the Star Motel, a notorious hot spot for drug deals.

“It’s not the greatest motel,” Beaver admitted to Ross, “but you don’t want to be out on the streets or be in a car.”

Since becoming a shop steward for his local union, he doesn’t just see motel life as bad luck. Many of his neighbors, he says, are fellow Disney employees down on their luck as well. “I got to see, firsthand, how the families in there are struggling,” Beaver said. “What I have experienced in this motel is a life-changing experience I’ll never forget, and I’ll fight for the people that can’t do so for themselves.”

That fight was taken to Disney World’s front door in 2017, when protestors for the Service Trades Council Union — which represents several unions and approximately 43,000 Disney cast members — marched at the park’s Crossroads entrance, demanding a pay increase from $10 to $15 an hour.

“It looked for all the world like a picket at the dream factory gate,” writes Ross. “But, since the union contract forbids picketing, it was billed as a ‘parade’.”

When that failed to make a convincing case, another march was planned in April of 2018, near the Disney Springs entrance. Thousands of protestors carried picket signs and balloons with phrases like “End Disney Poverty.” The protest looked less like a parade this time, with unsmiling employees chanting, “We work, we sweat, put a raise on our check.”

In August 2018, the union reached a deal with Disney to gradually increase wages to $15 an hour by October 2021. It was a shocking victory for many Disney long-haulers.

“Not one cast member I knew thought we could get $15,” said Alcantara-Anderson, who’s also a shop steward at Local 362, which represents many of the lowest-paid cast members. The new union contract had the potential to help many of her co-workers “move off food stamps and into their own apartments,” she says.

“Disney’s response to its employees’ acute housing needs has been dismal.”

“Sunbelt Blues” author Andrew Ross

That’s exactly what happened for some. It allowed Gutiérrez, the short-order cook, to escape the seedy motel and rent a two-bedroom apartment. “I feel human,” she says, “living in a home that gives me some self-respect.”

Another cast member who made the move told Ross that she and her family “had our first Thanksgiving dinner when we didn’t have to sit on my son’s bed.”

Although Mike Beaver had enough income now to move, he opted to stay at the Star Motel to help those Disney employees who still couldn’t afford to leave. He performed basic maintenance on the building and even stocked a food pantry in one of the vacated rooms.

“God has told me to stay here and to stand up for what’s right,” he told Ross. “I am rattling the cages of the politicians because I am in a position to put them on notice about the problems in the motels and the low pay of cast members.”

Two months later, the motel — which had gone into foreclosure for loan defaults and unpaid property taxes — was scheduled to be demolished, and Beaver finally checked out and into the Sun Inn motel, another low-cost housing option where he remains today.

In the end, the slight bump in pay didn’t fix the housing crisis.

Cole Washington, a security officer for Disney World, has tried leaving the motels and renting an apartment, but the prices keep going up. He suspects that whenever potential landlords “hear that I am Disney, I’m sure they jack up the rent.”

Kareem Burrow, another Disney employee, has heard plenty of tales from his co-workers of landlords squeezing more rent after reading news reports of Disney raising wages. “There is a crazy perception that Disney workers are well off,” he said.

Alcantara-Anderson has seen it happen every time Disney offers even a tiny raise. “When wages rise like a helium balloon, rents shoot up like a Roman candle,” she says. Which is why she’s staying in her rental home for now, despite the long commute.

Since the union standoff, Alcantara-Anderson — a woman who once won the Disney Heroes Award, one of the park’s highest honors, for performing CPR on a guest — is now making $17.70 an hour, up from $11.50 five years earlier. It’s enough to keep her from sleeping in the parking lot because she can’t afford gas, but not enough for a home of her own, close enough to the park to get back to her family before midnight.

Read the full article Here