‘Woke’ billionaire who trashed the Founding Fathers profited off Eskimos, oil

Billionaire David Rubenstein’s philanthropic efforts trash the Founding Fathers, even though his own business has made a fortune from deals that have profited off the less fortunate.

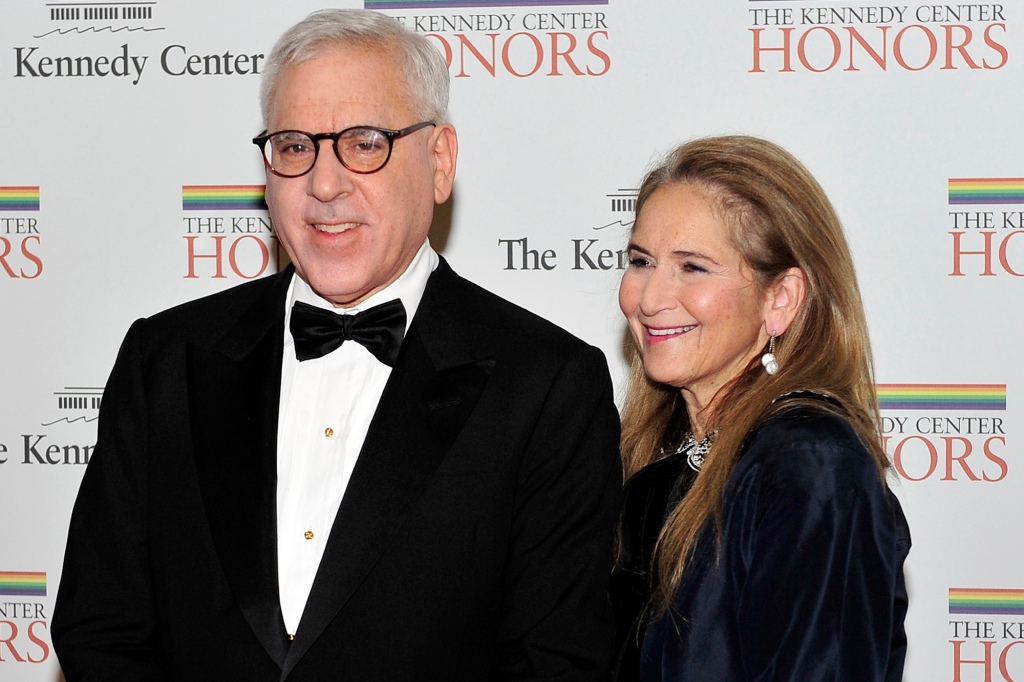

Since 2013, Rubenstein, 72, who co-founded the private equity giant the Carlyle Group, has given millions to entities that repair and upgrade historical monuments and landmarks like the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument as well as Monticello and Montpelier, the homes of US presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. But some say the restoration at the presidential homes has recast the presidents as sinister racists while downplaying their accomplishments.

Recent visitors to Monticello and Montpelier have flooded Trip Advisor with complaints about how the former presidents have been virtually reduced to villainous slaveholders in lectures by the tour guides while books on anti-racism and critical race theory by Ibram X. Kendi and Ta-Nehisi Coates dominate the gift shops.

Remarked Dan A. after his visit to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello: “Do your history homework before going, so you can appreciate this great American… the woke tour guide will leave you feeling like he started the Ku Klux Klan.” “They have demonized the founding fathers now,” wrote another recent visitor to Monticello. “Same thing with Madison’s home. I would stay away from places like this. It’s not worth the propaganda.”

But a quick dive into Rubenstein’s backstory shows he’s not so pure himself. He made his initial fortune in the 1980s by exploiting a tax loophole in Alaska allowing him to profit from deals made with Natives — and the Rubenstein family has been expanding their influence in the 49th state ever since.

In 2014, Rubenstein’s then-wife helped elect a governor in Alaska who in turn opened up the state’s $80 billion Permanent Fund, a fraction of which is managed by the Carlyle Group, to special interests. Rubenstein’s daughter was appointed to the board of that fund last month.

“Here’s a guy who has taken advantage of other people to climb to the top while he expects perfection from the Founding Fathers,” Dan Fagan, a talk show host and journalist who covered Alaska for 25 years, told The Post. “Because of the Rubenstein family and how [his ex-wife] influenced the change in the state’s sovereign fund, the average Alaskan family has lost tens of thousands of dollars.”

The only child of a Baltimore mailman and homemaker who grew up in a two-bedroom row house, Rubenstein began as a staffer in the Carter Administration and rose to the heights of finance, politics and society. He co-founded the Carlyle Group 35 years ago and is now worth an estimated $3.6 billion.

The white-haired, bespectacled Rubenstein, who divorced after a long marriage in 2017, is also longtime history buff, and has been dubbed the “Patriotic Philanthropist” in fawning profiles that align with his origin story.

“I came from very modest circumstances,” he told an audience in 2018 at the National Churchill Library and Center at the George Washington University. “I want to be able to say thank you for my success in this country, and I owe it to the country. And I’m doing it in a way that’s designed to draw attention to [American] history and heritage.”

Just a few of his roles (past and present) include chairman of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, chairman of the National Gallery of Art, chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and former chairman of the Smithsonian. President Joe Biden and his wife spent last Thanksgiving at Rubenstein’s lavish $20 million Nantucket home.

But his start in business was less elegant.

In 1987, Rubenstein and his Carlyle Group co-founder Stephen L. Norris got the bulk of their initial capital from some unwitting native Alaskans who owned floundering oil and timber companies. The deal was called “The Great Eskimo Tax Scam” by critics at the time, including author Michael Lewis who claimed the half-joking phrase was also used in the offices of the Carlyle Group.

The “scam,” according to Lewis, who wrote a critical essay of Rubenstein and the scheme in 1993, “grew out of a brief, curious tax loophole that permitted Alaskan companies owned by Eskimos to sell their losses for hard cash to other American corporations. By offsetting the Eskimo losses against their gains, American corporations were able to avoid income taxes. All of a sudden there was a business in matching up profitable American corporations with Eskimos. Rubenstein and Norris spotted the window of opportunity and jumped through.”

The leap apparently went smoothly.

“Norris and Rubenstein had no trouble finding needy Eskimos,” said one report at the time. “They flew the struggling CEOs into Washington, wined them and dined them, and got them just as hooked on free money as the crack cocaine that enterprising drug dealers were just then bringing to America’s Lower 48. The partners took 1% of the transaction for themselves and juiced a billion dollars of losses through the system.”

That “Eskimo” money fueled the rise of the fledgling Carlyle Group, which today manages more than $325 billion worth of assets on six continents and is one of the largest private equity firms in the world. (The firm took its name from the Carlyle Hotel in New York but there is no other connection.)

But Rubenstein’s Alaskan adventure didn’t end there.

In 2001, his then-wife, Alice Rogoff, whom he met when they both worked at the Carter White House, first visited Alaska and liked it so much she bought a house there (apparently in her own name). Several Alaska political insiders say she appeared to have a genuine affinity for the state and its people, including promoting Alaskan art. She learned to pilot her own plane and flew it along the famed Iditarod race in 2014 with her then-pal Ghislaine Maxwell. David Rubenstein visited only rarely, sources told The Post.

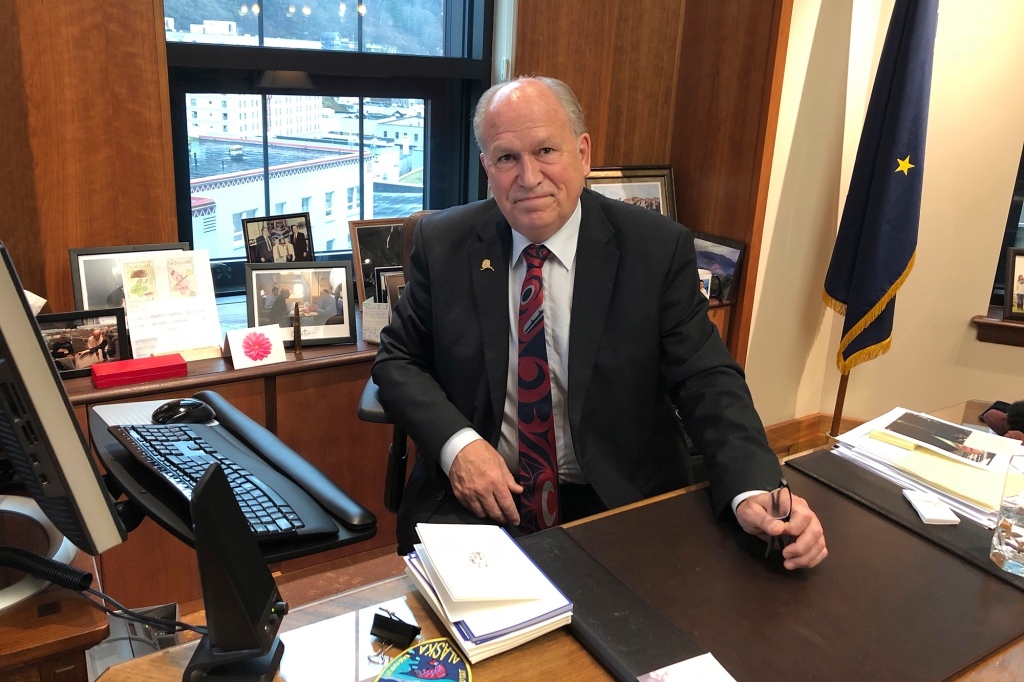

In 2014, Rogoff bought the paper of record, the Anchorage Daily News. Almost immediately after purchasing the paper, Rogoff published a number of hit pieces about the sitting Republican governor Sean Parnell and his allegedly ineffectual response to a sex harassment scandal in the Alaska National Guard. Rogoff successfully lobbied via numerous editorials for the election later that year of Gov. Bill Walker, who was backed by the Democrats.

“It was the clearest case of journalism malpractice and propaganda ever seen in Alaska,” Fagan wrote in a recent op-ed in Must Read Alaska.

In 2015, Rogoff penned a column in her own newspaper suggesting that the state’s massive Permanent Fund, now worth $80 billion and the biggest sovereign wealth fund in the country, should be distributed differently, taking much of the power away from ordinary citizens and putting it in the hands of legislators. “Huge cash reserves and assets” in the fund could be used as leverage to borrow more money, she wrote.

A year later, her hand-picked governor carried out her plan.

Using his veto power, Walker permanently restructured the way the Permanent Fund is handled, empowering legislators to control the portion that is distributed to Alaska residents via dividends — making a fund that was designed to be politics-proof now a purely political tool.

Created in 1976 via an amendment to the Alaska constitution, the Permanent Fund was designed so about 25 percent of the royalties from oil money flowing through the Trans-Alaska pipeline would be placed in a dedicated fund for future generations, who would no longer have oil as a resource. Alaskan residents receive yearly dividend checks that typically range anywhere from $800 to $3,200.

Originally designed to distribute dividends based on five-year averages, Walker vetoed that rule and turned the decision over how to disperse the monies to state lawmakers. That year, Alaskans got an annual check that was 50 percent lower than what it would have been with the original statutory calculation, according to state media reports.

“Rogoff knew that Gov. Walker would transform the Permanent Fund from a way to share the state’s resource wealth with the people through a yearly dividend check to instead a mechanism allowing the Juneau and Washington DC swamp to raid the fund’s considerable wealth,” Fagan wrote.

‘Here’s a guy who has taken advantage of other people to climb to the top while he expects perfection from the Founding Fathers.’

Dan Fagan, a journalist who has covered Alaska for 25 years.

“Since they shifted the Permanent Fund structure … with the help of Alice Rogoff’s proxy as governor, a family of five in Alaska is out $60,000 and counting,” Fagan told The Post last week. “The checks families get are so much smaller.”

The Carlyle Group began managing assets in the Permanent Fund in 2005 and now manages just under $1 billion of the fund, according to public records. In the early aughts, the Carlyle Group was also the subject of myriad conspiracy theories, many of which revolved around its close relationship with the Bush family, the Saudis and the military-industrial complex. Dan Briody’s 2003 book, “The Iron Triangle: Inside the Secret World of the Carlyle Group” detailed the allegedly shadowy dealings of the company.

Two weeks ago, Gabrielle Rubenstein, the daughter of Rubenstein and Rogoff, was appointed to the Permanent Fund Corporation’s board of trustees.

“The people who structured the fund to begin with were wise,” Suzanne Downing, a former speechwriter for Gov. Parnell who now runs the news site Must Read Alaska, told The Post. “They specifically designed it to keep it out of the hands of politicians and special interests. Now it’s become the biggest thing the legislature fights about every year. Alice Rogoff was the key person behind getting Walker into power and getting that shift made to the fund.”

At the same time, Downing said she believes that Rogoff’s ex-husband “sees the Permanent Fund as a gold mine.”

After Walker was elected, the Anchorage Daily News began losing money. Rogoff filed for bankruptcy in 2017 — the same year she and Rubenstein divorced — and had to go to an “embarrassing” trial where electricians and other contractors who worked for the paper said she had stiffed them, Fagan told The Post. She eventually sold the paper for $1 million, a $29 million loss.

Still, new board appointee Gabrielle and both her mother and father “are very close and at the end of the day it’s all about Rubenstein Inc and protecting the family,” Downing said. “It’s so easy to take over Alaska if you have money. People in Washington DC and New York look at us like a bunch of rubes and hillbillies.”

Meanwhile, in May, the Harvard Crimson ran an editorial calling for Rubenstein’s ouster as the head of the Harvard Corporation — one of many influential positions he holds — because of the Carlyle Group’s investment in more than 70 companies it said pollutes the planet. “Rubenstein has a long record of trying to depict himself as a patron of arts and culture to distract from his dangerous record,” the editorial said. “(The Carlyle Group) is a firm that fuels the climate crisis, pollutes and victimizes poor and vulnerable communities, and profits off it all.”

A spokesman for Rubenstein told The Post Thursday that “Mr. Rubenstein’s gifts honor the genius and legacy of our founders while telling the stories of the people they enslaved” and did not elaborate further. Alice Rogoff did not respond to a call from The Post. A friend of hers in Alaska who is an attorney told The Post he did not know if she had legal representation.

Read the full article Here